Svalbard, Norway

Nigh-On 80°N. As Human & As Accessible As The High Arctic Gets. 62,000 km² Of Majestic Arctic WildernessBrrr! Overlooking Longyearbyen, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 23, 2018.

“It was an effort tonight, night 4 here on Svalbard, to scale the steep & icy valley slopes of Sverdruphamaren to get a vantage point overlooking Longyearbyen. The mercury was reading -15 °C (5 °F), to say nothing of what it felt like allowing for the windchill (at times the Longyear Valley the town sits in acts like something of a wind tunnel). Needing to adjust camera settings necessitated me dispensing with my gloves. My fingers stopped working for a while – numbness, just prior to the onset of frostbite, is the warning sign – but my camera didn’t miss a beat.”

Svalbard, Norway – Introduction & Arrival

Trust me, when you’re this high, latitudinally speaking of course, geodetics is so much fun. Cold fun, but fun nonetheless. I’m nigh-on 80°N. 78.2°N to be exact, 78.2 degrees north of the equator that is, the highest I’ve ever been and likely ever will be. I’m on a distant & shivering archipelago called Svalbard (![]() ) that’s well inside the Arctic Circle, the most northerly of the earth’s five major circles of latitude that’s sitting (and slowly drifting) at only 66°N. I’ve been close to the Arctic Circle before when in Anchorage, Alaska (61.2°N). Even closer still when in southern Iceland (tantalisingly close at 64.1°N). This time, however, I’ve crossed the line and I’m in the Arctic proper. The High Arctic even. Yes I’m still in Europe – Norway to be percise – but I’m closer to Alaska than Athens by being here half way between mainland Europe and the North Pole, that northernmost point of the Earth’s axis that’s only 1,338 kilometres (831 miles) away. Indeed, being here in the quirky town of Longyearbyen, Svalbard’s largest settlement and the northernmost real town on earth, makes me one of the most northerly 3,000 people on the face of the planet. In fact, there’s a rather high probability that right now I’m the northernmost Irishman alive, and conceivably the coldest too considering it’s -19 °C (-2 °F) outside, or -28 °C (-18 °F) with the windchill. Brrr! But at least there’s daylight this time of year to accompany the mordacious frigidity. It – the light – will allow me explore some of the 62,000 km² of unrivaled & pristine Arctic wilderness that I find myself in the midst of; as a visitor there’s very little else to do up here, positively no other reason to swing by should you, like me, decide to do so.

) that’s well inside the Arctic Circle, the most northerly of the earth’s five major circles of latitude that’s sitting (and slowly drifting) at only 66°N. I’ve been close to the Arctic Circle before when in Anchorage, Alaska (61.2°N). Even closer still when in southern Iceland (tantalisingly close at 64.1°N). This time, however, I’ve crossed the line and I’m in the Arctic proper. The High Arctic even. Yes I’m still in Europe – Norway to be percise – but I’m closer to Alaska than Athens by being here half way between mainland Europe and the North Pole, that northernmost point of the Earth’s axis that’s only 1,338 kilometres (831 miles) away. Indeed, being here in the quirky town of Longyearbyen, Svalbard’s largest settlement and the northernmost real town on earth, makes me one of the most northerly 3,000 people on the face of the planet. In fact, there’s a rather high probability that right now I’m the northernmost Irishman alive, and conceivably the coldest too considering it’s -19 °C (-2 °F) outside, or -28 °C (-18 °F) with the windchill. Brrr! But at least there’s daylight this time of year to accompany the mordacious frigidity. It – the light – will allow me explore some of the 62,000 km² of unrivaled & pristine Arctic wilderness that I find myself in the midst of; as a visitor there’s very little else to do up here, positively no other reason to swing by should you, like me, decide to do so.

FIRST GLIMPSE || A portion of Spitsbergen, the Svalbard archipelago’s largest & only inhabited island, as seen from Norwegian Air flight DY396 from Oslo, 2,313 kilometres (1,437 miles) south of here on the Norwegian mainland. Svalbard, Norway. March 20, 2018.

Some were probably very familiar with the approach to Svalbard and have no doubt seen it all before, happy to pass the time reading. For me it was all fascinatingly new. There wasn’t a whole lot to see and what there was to see was very, very blue (it was approaching 8 p.m.). Everything projected frigidity, just as I expected it would.

SVALBARD AIRPORT, LONGYEAR || Velkommen. Waiting for baggage that was never to come (at least not yet) in the arrivals hall of Svalbard Airport, Longyear, the northernmost airport in the world with scheduled public flights. Svalbard, Norway. March 20, 2018.

It’s not a whole lot of fun being in -19 °C (-2 °F) Longyearbyen when your luggage, housing all your winter gear, didn’t follow (actually, that’s a bearfaced lie – it’s still awesome to be here). My luggage whereabouts & eventual arrival day & time remain unknown, the Customer Service Agent dealing with me in the airport arrivals hall very obviously reluctant to dispense assurances; ‘your bag is either in Dublin or Oslo’ and will be here ‘sometime before Sunday’, departure day, is what I’ve been told. Oh well. Time to improvise.

– VisitSvalbard.com

Svalbard - Titbits

Suffice it to say, Svalbard is a bit off the beaten track, not your typical getaway location. It’s an inhospitable, strange & unique land, one governed by some equally strange and unique rules and regulations and all shaped, like everything else around here, by the archipelago’s extreme everything. Here are a few fun fast-facts I discovered researching the place, choice morsels of information, some of which are elaborated on throughout the posting with typical dMb verbosity.

LOCATION & EXTREMES – CLIMATE, THE LONG POLAR NIGHT & THE MIDNIGHT SUN || The Svalbard archipelago, comprising three main islands and numerous smaller islands, sits frozen at the northernmost tip of Europe… Located between the 74° and 81° parallels North, Svalbard’s settlements are the northernmost permanently inhabited places on earth… The archipelago is far higher than anywhere in Alaska and Arctic Russia with only a handful of islands in the extreme north of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago and the extreme northern tip of Greenland being higher… Svalbard, however, wasn’t always this high. The archipelago’s abundant coal deposits, fossilised remains of a tropical forest and the reason humans settled here in the first place, are remnants of a time many millions of years ago when present-day Svalbard was situated much further south… Although the archipelago features a typically severe Arctic climate, Svalbard’s climate is milder when compared with other regions at this latitude. Indeed, the so-called ‘tropical’ Arctic Archipelago would be icebound 365 days of the year if not for the West Spitsbergen Current, the northernmost branch of the North Atlantic Current system, its comparative warmth making the west of the archipelago both habitable & accessible… Much like Antarctica in the Southern Hemisphere, Svalbard receives little precipitation (plenty of snow, however) and is thus classified as ‘arctic desert’… The higher air pressure on Svalbard makes it more difficult to breath here than on the mainland… The Svalbard ground is perennially frozen – permafrost – to a depth of 500 metres & only the very top layer, the 1-metre-wide upper active layer, defrosts at all, and even then for only the 3-4 months of so-called summer. Outside of the summer months, or around about now, everyone is freezing, everything frozen solid. Below freezing for 8 months of the year, the average winter low is -15 °C (5 °F) with a record low of -46 °C (-51 °F) (a domestic deep freeze chills out at about -19 °C (-2 °F))… From the setting sun of late October until the rising sun of mid-February, there’s constant darkness, the so-called Long Polar Night, & the sun never sets, the so-called Midnight Sun, between mid-April and late August… Svalbard’s location in the far north means it feels the impact of climate change most acutely – temperatures here have risen 6 degrees over the course of the past 3 decades. That’s global warming for you.

LOCATION & EXTREMES – CLIMATE, THE LONG POLAR NIGHT & THE MIDNIGHT SUN || The Svalbard archipelago, comprising three main islands and numerous smaller islands, sits frozen at the northernmost tip of Europe… Located between the 74° and 81° parallels North, Svalbard’s settlements are the northernmost permanently inhabited places on earth… The archipelago is far higher than anywhere in Alaska and Arctic Russia with only a handful of islands in the extreme north of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago and the extreme northern tip of Greenland being higher… Svalbard, however, wasn’t always this high. The archipelago’s abundant coal deposits, fossilised remains of a tropical forest and the reason humans settled here in the first place, are remnants of a time many millions of years ago when present-day Svalbard was situated much further south… Although the archipelago features a typically severe Arctic climate, Svalbard’s climate is milder when compared with other regions at this latitude. Indeed, the so-called ‘tropical’ Arctic Archipelago would be icebound 365 days of the year if not for the West Spitsbergen Current, the northernmost branch of the North Atlantic Current system, its comparative warmth making the west of the archipelago both habitable & accessible… Much like Antarctica in the Southern Hemisphere, Svalbard receives little precipitation (plenty of snow, however) and is thus classified as ‘arctic desert’… The higher air pressure on Svalbard makes it more difficult to breath here than on the mainland… The Svalbard ground is perennially frozen – permafrost – to a depth of 500 metres & only the very top layer, the 1-metre-wide upper active layer, defrosts at all, and even then for only the 3-4 months of so-called summer. Outside of the summer months, or around about now, everyone is freezing, everything frozen solid. Below freezing for 8 months of the year, the average winter low is -15 °C (5 °F) with a record low of -46 °C (-51 °F) (a domestic deep freeze chills out at about -19 °C (-2 °F))… From the setting sun of late October until the rising sun of mid-February, there’s constant darkness, the so-called Long Polar Night, & the sun never sets, the so-called Midnight Sun, between mid-April and late August… Svalbard’s location in the far north means it feels the impact of climate change most acutely – temperatures here have risen 6 degrees over the course of the past 3 decades. That’s global warming for you.

Heed the signs. The Polar bear, the icon of the Arctic & prowling ‘Gjelder hele Svalbard’, all over Svalbard. There are two of these signs, which are quite the photo op, sitting on the main (only) road either side of Longyearbyen. They indicate the edge of the town’s so-called safe zone, the area outside of which one is expected to carry protection (a rifle, a flare gun, a prayer etc.) against polar bear attacks. Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 24, 2018.

FORMATION, LANDSCAPE (60% ICE, 27% ROCK, 13% VEGETATION) & RESERVES || A frozen land of glaciers, peaks & fjords, the landforms of Svalbard were created through repeated ice ages, when glaciers cut the former plateau into fjords, valleys and mountains… Two-thirds of the 62,000 km² archipelago, corresponding to approximately 20% of the area of mainland Norway, is permanently covered by snow & ice (60% of Svalbard is covered in glaciers), and approximately 65% of this largely untouched yet fragile natural environment, an area roughly the size of Denmark, is protected in the form of seven national parks, twenty-three nature reserves, numerous plant & bird reserves and a lone geotropic reserve (Svalbard is on Norway’s tentative list for nomination as a UNESCO World Heritage Site)… If not blanketed in snow & ice, Svalbard would be barren, rugged and desolate, a landscape resembling a time harking back to the Ice Age. Its mountains, the tallest of which is Newtontoppen (1,717 metres / 5,633 feet), are crumbling heaps of rapidly disintegrating sedimentary rock… The landscape, 27% of which is barren rock, has no trees, there is no arable land (nothing of note grows here) & only 13% of Svalbard is vegetated.

THE SVALBARD TREATY || Svalbard is officially part of Norway as per article 1 of the 1920 Svalbard Treaty, a unique set of articles, 10 in total, giving unique rights to a unique land. Upheld by The Governor of Svalbard (Sysselmannen på Svalbard in Norwegian), the administrative team responsible for public services and the Norwegian Government’s highest-ranking representative on Svalbard, the treaty ensures the archipelago remains demilitarised (and natural, article 9); ensures the citizens of the 40 Treaty signatories (as of late 2010) are afforded equal rights to entry and residence while allowing signatory nations rights to engage in research or commercial activities, mostly mining; while article 8 ensures taxes collected can only benefit Svalbard (in reality not only are taxes collected not siphoned off to the mainland but the Norwegian state greatly subsidises Svalbard’s budget).

ENVIRONMENTAL & CULTURAL PROTECTION || Entrusted, as per the Svalbard Treaty, with preserving the natural & cultural environment, Norway takes the task very seriously – environmental & tourism regulations means large swaths of the archipelago are off-limits (you must seek permission from the Governor’s Office to strike out independently into the wilderness outside the so-called Management Area 10, the central parts of the island of Spitsbergen, Svalbard’s largest and only permanently inhabited island) and anything on the island dated pre-1946 is protected as a cultural monument or artefact, however nondescript it may appear. Thread carefully.

– From The Governor of Svalbard’s Experience Svalbard on Nature’s own terms pamphlet

Coal mining has been the backbone of the Svalbard economy for much of the last century. However, today only Norway & Russia have a mining presence on Svalbard, token operations that serve more a political purpose than an economic one – while there are still abundant reserves of coal on Svalbard, mining here is no longer an economic or socially viable prospect. The Svalbard past is visible and never far away. The hills surrounding Longyearbyen, in particular, remain littered with rusting mining remnants from days of old, including these photogenic cableway trestles with cables and buckets for the transport of coal from the mines to the coal depot and now protected as cultural artefacts, important cultural monuments from the activities that provided the basis for settlement on Svalbard. Elsewhere empty buildings with broken windows sit crumbling; upturned derailed cars lay beside twisted rails; rusty boilers, wheelbarrows and scrap iron in all shapes and sizes lie uncovered by the thin soil cover littering the barren, rugged and desolate landscape as nature slowly inches its way back to reclaim the forever-scared land. Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 23, 2018.

– Nord for det øde hav, Liv Balstad, 1956

INHABITANTS WORK & TRANSPORT || There are no indigenous inhabitants – anyone who lives here chooses to do so and only the best in their field get the available jobs, something that creates a sense of enthusiasm and vested interest among the population that probably does not exist anywhere else on earth… While slowly changing, settlements on Svalbard are still essentially company towns, the Norwegian state-owned coal company employing nearly 60% of the Norwegian population on the archipelago and the Russian state-owned Arktikugol (Arctic Coal) the majority of Russians & Ukrainians. Almost all housing is owned by the various employers and institutions and rented to their employees (there are only a few privately-owned houses, most of which are recreational cabins). Because of this, it is rather unusual to live on Svalbard without working for an established institution… Approximately 25% of the population changes every year, the average residence period being 7 years (it seems this place, and/or its harsh environment, has a residential shelf life)… The average income is higher than on the mainland, income tax for those who work here is set at 8% and most goods are sold tax-free, a good thing given the high prices… Although the same laws apply in Svalbard as they do on the mainland, and unlike mainland Norwegians, residents of Svalbard are not entitled to social security benefits (everyone must be self-sufficient), and nor are they automatically entitled to residency on the mainland… There are more registered snowmobiles than residents, more polar bears than snowmobiles… There are less than 50 kilometres of roads on the whole archipelago, mostly in the vicinity of Longyearbyen and other settlements, and there are no roads or arranged transport between settlements – it’s boat or a stiff walk in summer, snowmobile or a dogsled in winter.

Snowmobile. De facto winter transport. Longyearbyen, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 21, 2018.

CONNECTED || It may be remote, but Svalbard is very much connected thanks to the 1,440-kilometre-long (890 mile) Svalbard Undersea Cable System, a dual fibre optic line from Svalbard to Harstad on the Norwegian mainland. It was installed in 2004 and aside from providing the high-speed internet access enjoyed by the residences & businesses of Longyearbyen today, it also provided sufficient bandwidth for SvalSat, the Svalbard Satellite Station. Opened in 1997 and consisting of 31 multi-mission and customer-dedicated antennas, today SvalSat is the world’s largest commercial download station for satellite data, its location at 78°N making it one of only two ground satellite stations (the other is in Antarctica) that can cover all 14 of the orbits that a polar satellite flies in a single 24-hour period.

The various antenna of SvalSat, the Svalbard Satellite Station, atop the 464-metre-high plateau-shaped Platåberget. A parting shot captured early in the morning shortly after takeoff for the Norwegian mainland, Adventfjorden (Advent Fjord) & the runway of Svalbard Airport, Longyear in Hotellneset, 3 kilometers from Longyearbyen (which fronts Adventfjorden on the other side of Platåberget), can be seen to the left of the image. Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 25, 2018.

(STRANGE) LAWS || It’s as easy to hire a gun as it is a snowmobile (licences are required for both) as Svalbard’s law states that everyone of age must carry a firearm, or to travel with an armed escort, anywhere outside of settlement safe zones as protection against polar bears who can appear anywhere and at any time (although it is illegal to carry a loaded firearm within the settlements & shops provide lockers for the storage of (unloaded) guns)…

No guns allowed. COOP supermarket/grocery store, Longyearbyen, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 23, 2018.

Unnconditionally protected since 1973, it is strictly prohibited – not to mention a probable Darwin Award-worthy act of suicide – to seek out, stalk or disturb a polar bear (they can quickly overheat and die of stress) and they can only be killed in an extreme emergency situation (and if you kill a bear, or even find one dead, you must report this to the Governor of Svalbard)…

Day 3 snowmobile guide polar bear protection. Just in case. Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 22, 2018.

Maybe because of the need to bear arms (bear… arms…), there’s a monthly limit, a quota, on the purchase of alcohol in Longyearbyen – 24 cans of beer & the equivalent in spirits (and in true company town fashion, all profit from alcohol sales, called ‘cork money’, is supposedly distributed to clubs and organisations in the town). This applies to all – locals have an alcohol quota card and visitors must show their arrival boarding pass to liquor up (a holdover from Longyearbyen’s company town coal mining days, & in a bid to keep the miners sober, it’s only a matter of time before this law is abolished in present-day, tourist-orientated Longyearbyen)… There are no cats allowed on Svalbard, they being a menace to the birds that flock here in the summer months (Svalbard is something of a birdwatchers paradise with no less than fifteen bird sanctuaries).

NO SICKNESS, NO DEATH (PLEASE) || People on Svalbard struggle to catch a cold/ the flu – the virus can’t survive here. It’s only the newly arrived who bring infections to the island, hence a period of quarantine is required for those arriving with the intentions of residing here for a period of time, especially children…

Closed for business. The penchant for permafrost to preserve not only bodies but also the nastiness that may reside in them means that even graveyards from yesteryear are protected cultural monument on Svalbard, including the haunting white crosses of the early 1900’s cemetery on the lower slopes of Platåberget on the southwestern edge of Longyearbyen. Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 23, 2018.

… Svalbard has an obvious aversion to death, somewhat ironic given that the most common protected cultural monument on the archipelago today are human graves. A place for the fit & young, there’s a dearth of middle age residents; no one is born here (pregnant women must go to the mainland); it’s illegal to kill things (flora, fauna and yourself, notwithstanding the ease at which you could accomplish the latter); and while some say it’s illegal to die here, a law that is hardly enforceable, it is at the very least against regulations and highly frowned upon to end your days on Svalbard (honest – the permafrost ensures there’s nowhere these days to be buried). Oh and there’s a USD $9M Global Seed Vault, a crop doomsday bank, dug deep into the permafrost high inside a mountain that’s designed to survive the melting of the polar icecaps and preserve the earth’s agricultural diversity in the case of Armageddon.

L-R: The slopes of Sverdruphamaren, the peaks of Adventtoppen & Hiorthfjellet across Adventfjorden (Advent Fjord) & the settlement of Longyearbyen as seen from the upper Longyear Valley, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 23, 2018.

Svalbard - History & Tourism

Svalbard History – Discovery, Whaling, Hunting, Trapping & Coal

Probably discovered in the 1100s by hardy Icelandic seamen and meaning ‘land with the cold coast’ in Old Norse, Svalbard lay largely ignored until June 17 of 1596 when Dutch explorer Willem Barentsz, on a third unsuccessful quest to find the Northeast Passage, named the main island of the archipelago Spitsbergen after the island’s craggy, needle-like peaks (Spitsbergen roughly translates to ‘pointed mountains’).

– Willem Barentsz, Dutch discoverer of Svalbard.

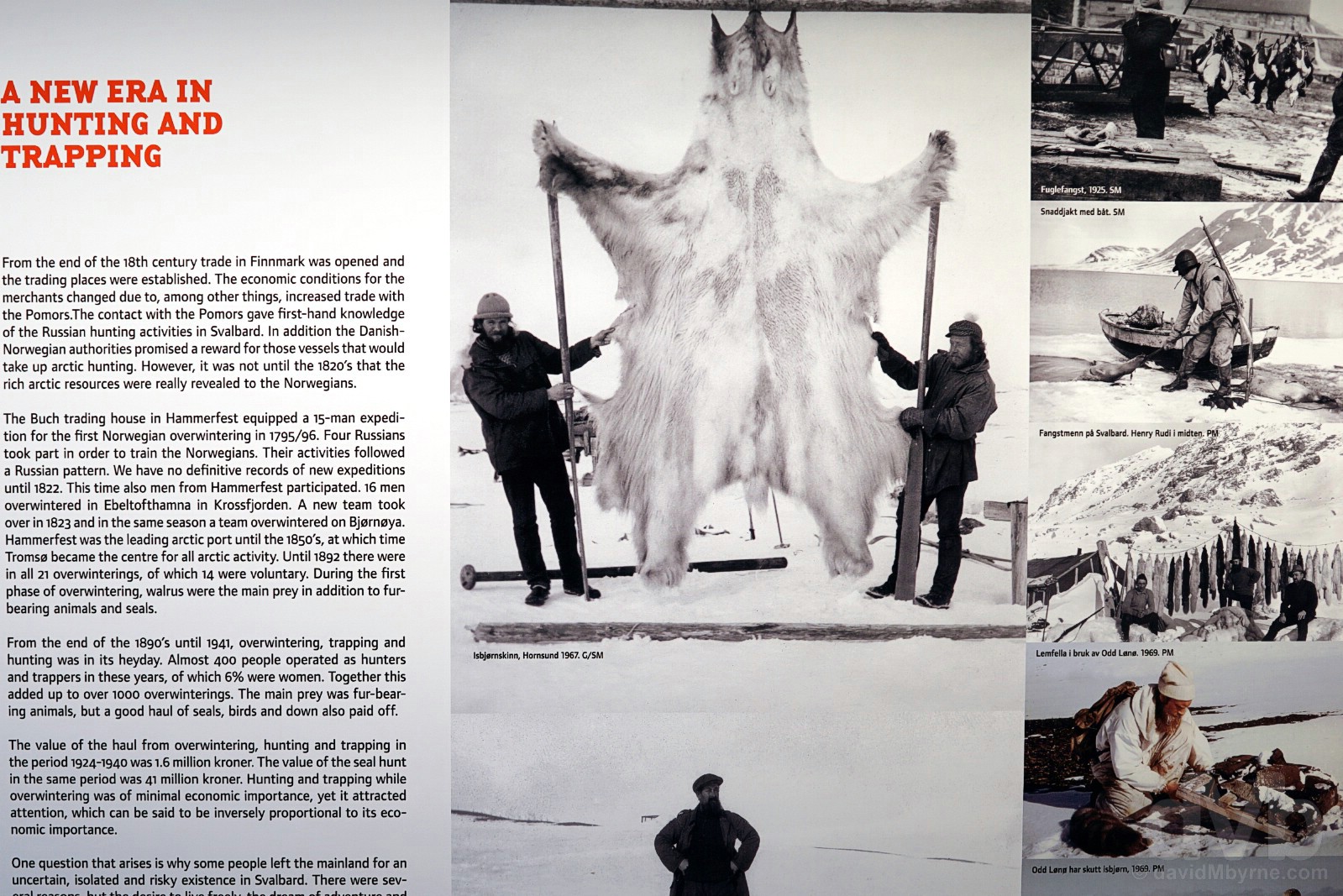

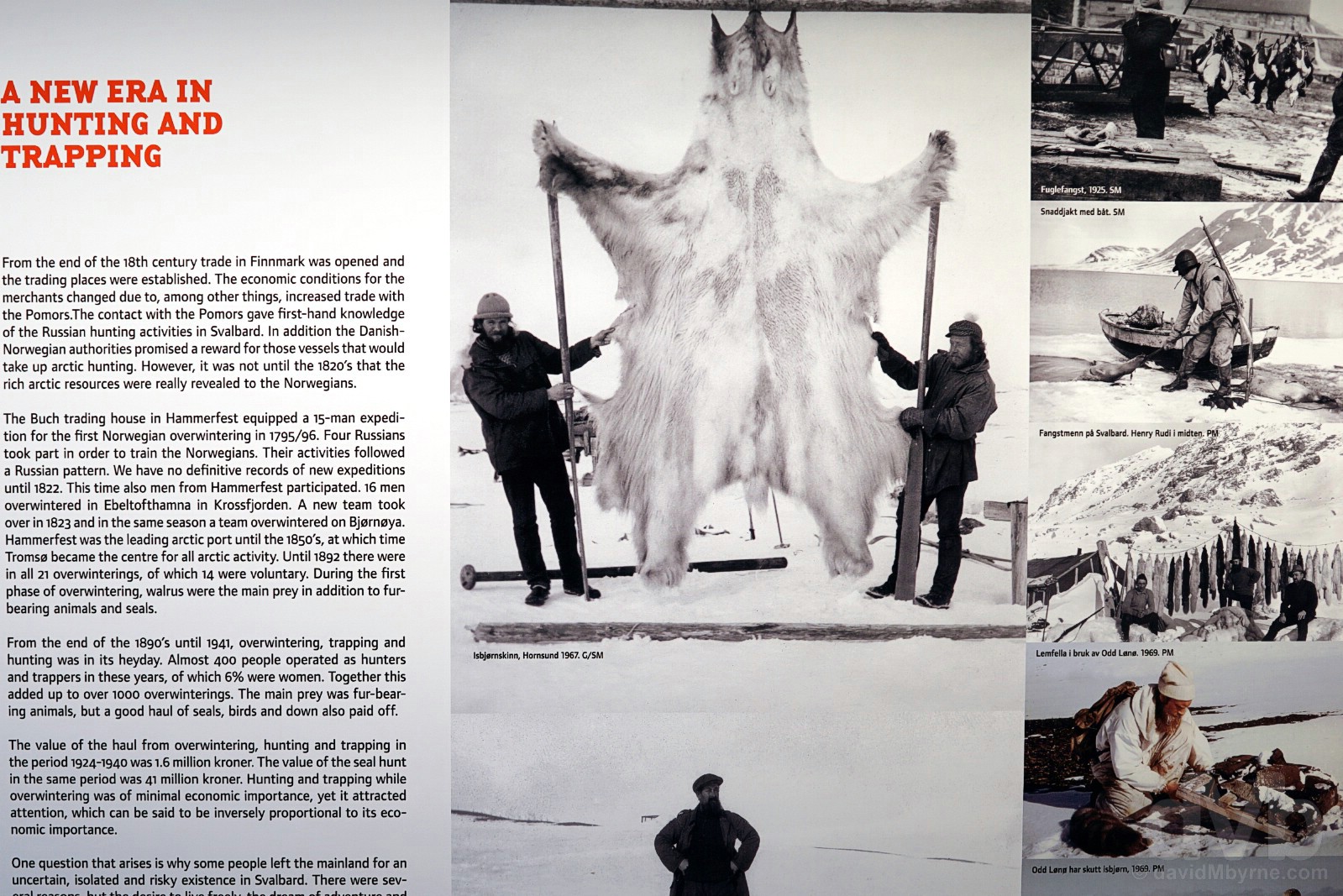

Uninviting, hostile & just a little removed by stretching to cross the 81st parallel north, the archipelago was used as a hunting and fishing and whaling base by the Dutch, British & Germans through most of the 17th & 18th centuries (during this time the great bowhead whale was tragically eradicated from Svalbard waters). A further two centuries of hunting & trapping (first by the Russians, between 1700 & 1850, & then the Norwegians, in the latter half of the 19th century) predictability wreaked havoc on Svalbard wildlife populations, primarily walrus, seals, arctic fox & the polar bear – one lone Norwegian trapper, Henri Rudi (1889–1970), killed 115 polar bears in a single year and over 700 over the course of a 4-decade career as a legendary arctic huntsman.

Trappers, who came north with the dream of the big catch, the free life and adventure in the vast Arctic wilderness, as highlighted in a display in The Svalbard Museum, Longyearbyen, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 23, 2018.

The 1899 discovery of rich coal deposits, the geological residue of a prehistoric tropical forest (Savlbard wasn’t always this far north and nor was it always as unforgivably cold), signalled an early 20th century boom in unregulated coal mining that necessitated the need for governance, something that was eventually provided by The Svalbard Treaty of the post-World War I Versailles negotiations. After centuries of the archipelago being called Terra nullius, a Latin expression meaning ‘nobody’s land’, the treaty, which was ratified in February 1920 but which didn’t come into force until August 1925, firmly established Norway’s sovereignty over Svalbard. It also granted “absolute equality” to any one of the treaty’s 46 original signatories (as of late 2010 there were 40 signatories) that wish to exploit mineral deposits, and it also allowed the Russians and the Swedes, who already had well-established coal mining operations on Svalbard prior to 1920, to stay put and to conduct business as usual.

Abandoned cableway trestles on the slopes of Sverdruphamaren as seen from the Longyear Valley in Longyearbyen, remnants of a time when coal, Svalbard’s abundant black gold, was crucial to fueling an increasingly industrialised Europe. Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 23, 2018.

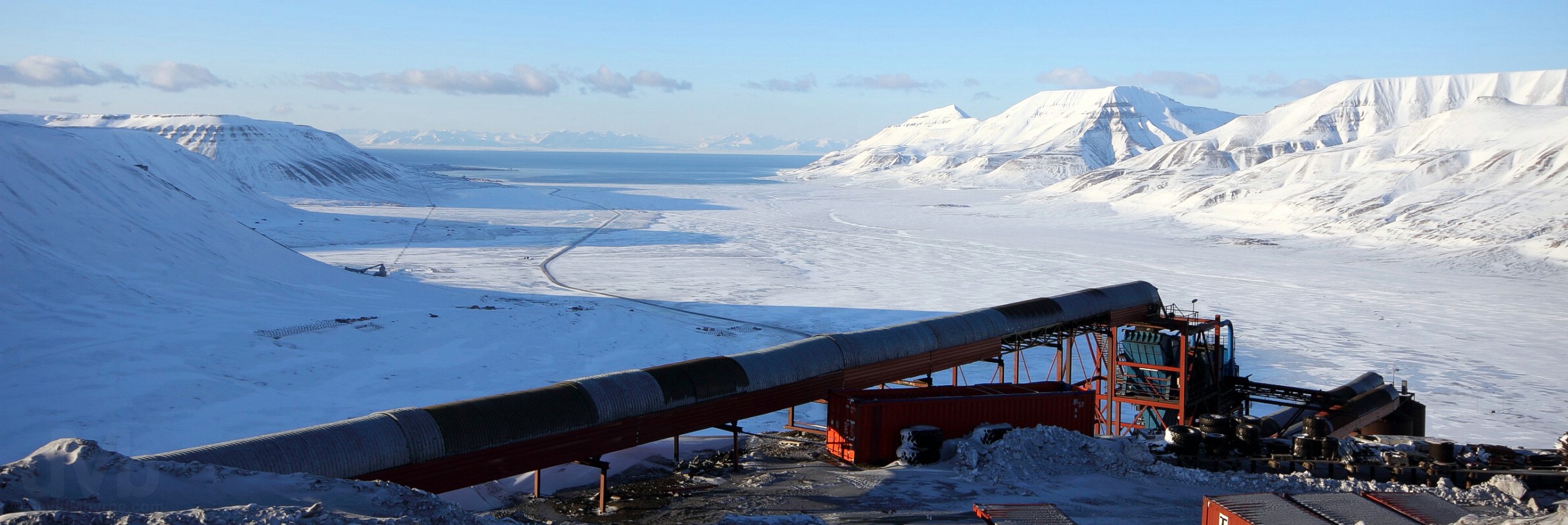

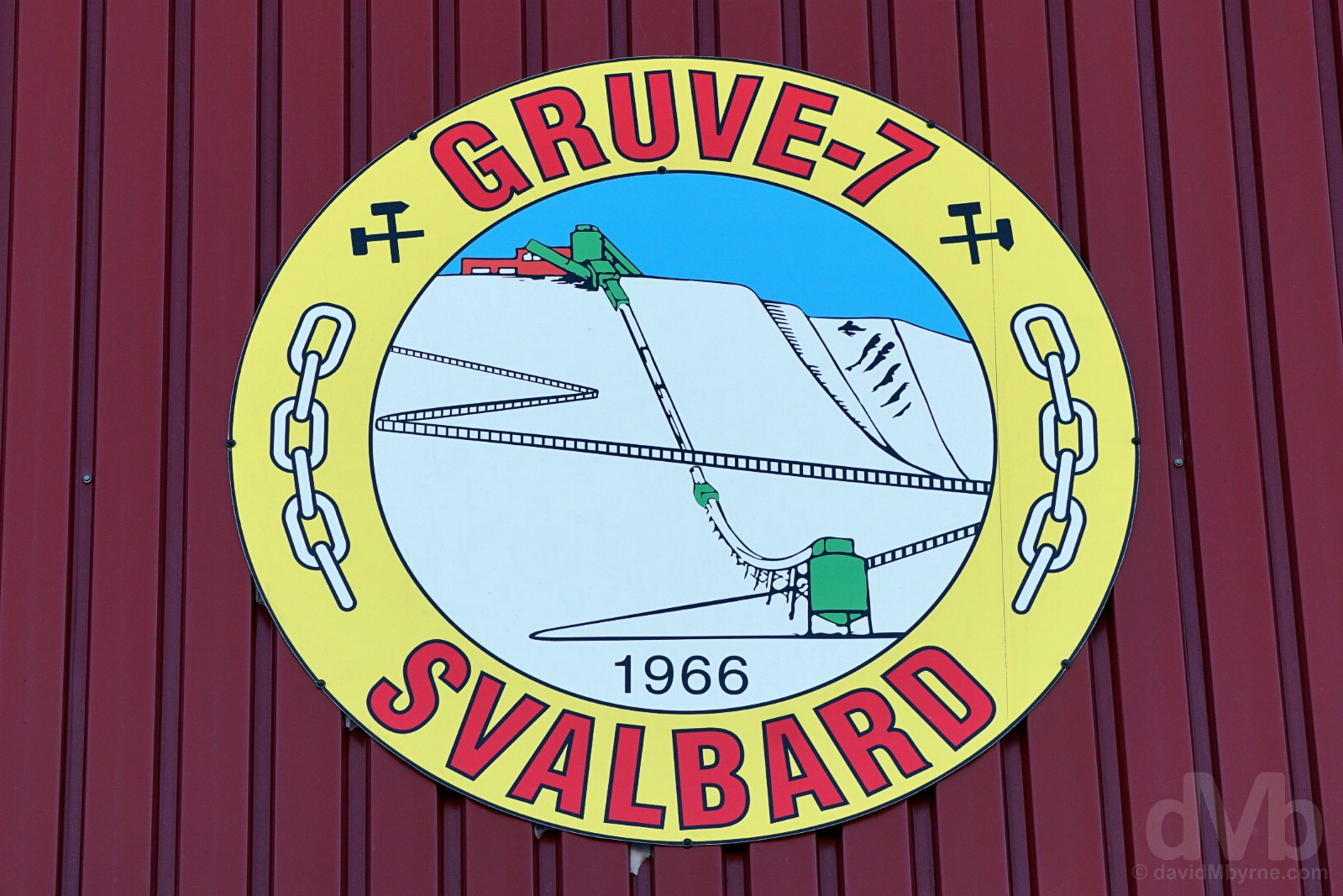

Although the Svalbard coal reserves are still abundant (and likely always will be), mining in the 21st century is neither economically or socially viable. That said, there is still mining activity on Svalbard, although only Russia & Norway have a mining operations in 2 unprofitable mines on life support – to mine here in 2018 is nothing more than a matter of principle, a presence here a political imperative for Russia in particular.

The second-most northerly Lenin statue in the world in Barentsburg, the second-largest settlement on Svalbard and the largest coal mining operation remaining on the archipelago. Some 55 kilometres west of Longyearbyen, this Soviet-era company town of 420+ mine-related inhabitants coupled with the eerie & frozen-in-time 1980’s Russian coal-mining town of Pyramiden (home to the northernmost Lenin statue on earth, abandoned in 1998 and – damn – inaccessible while I’m here) are two of the Svalbard’s biggest attractions, the remnants of Svalbard’s coal mining past driving its tourism offering of today. Barentsburg, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 22, 2018.

Svalbard Tourism

While the very first tourists to Svalbard were wealthy Europeans who arrived to hunt in the early 1800s aboard their own vessels, big cruise ships have been visiting the archipelago with some regularity since the 1890s; it was in 1896 that the first piece of tourism infrastructure, a wooden tourist cabin/hotel with space for 30, was built at what was to become today’s Hotellneset, about three kilometres along Advent Fjord from Longyearbyen proper and the location for the archipelago’s airport & present-day Longyearbyen’s main harbour.

– Léonie d’Aunet, La Recherche: An Expedition To The North, 1893

Tourists continued to come to Svalbard by ship right up until the airport was opened in 1975. Numbers were not high and very few who came ashore lingered – as a coal mining company town, a place of work, Longyearbyen had no tourist infrastructure whatsoever. As mining activity has dwindled, tourism has become increasingly important and now powers the economy of Longyearbyen, changing it significantly in the process. Nonetheless, and as one might imagine, the place is not exactly awash with tourists; Svalbard was rather restrictive with respect to the development of tourism and Longyearbyen itself has only been officially open to visitors since the 1990s with the establishment of ‘places to stay the night’, mostly resulting from the 1995 opening of the town’s Svalbard Polar Hotel, parts of which were shipped to the archipelago after being used as accommodations in the Olympic Village of the 1994 Winter Olympics in Lillehammer on the Norwegian mainland. With what tourism there is here focused on the amazing surrounds & environment, and with numbers increasing, the inevitable happened with the passing of legislation in early 2014 severely restricting the size of cruise ships that may ply the archipelago’s waters. Today cruise ships bring about 30,000 tourists a year to Longyearbyen (still less than 1% of the numbers that visit the northernmost reaches of mainland Europe, the so-called Cap of the North, the Arctic region covering the extreme north of Norway, Sweden, Finland & Russia) while its hotels claim over 100,000 overnight stays a year.

– Excerpt from the ‘Experience Svalbard on Nature’s own terms’ pamphlet as published by The Governor of Svalbard, the authority entrusted with ensuring Svalbard remains one of the world’s best preserved wilderness areas while trying to balance growth & profit with environmental awareness.

Oh yes. Wherever you have tourists you’ll find the multi-directional sign post, including this one outside the terminal of the archipelago’s Svalbard Airport, Longyear. Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 25, 2018.

Both a shivering remnant of hard & oft-tragic times past and a unique & forlorn outpost for Arctic research it may be, Svalbard today is also an exotic travel hotbed for the adventurous types, a boast-worthy bucket list travel destination par excellence – it’s the most accessible area in the largely inaccessible High Arctic, one of the outermost regions of the planet, providing an unparalleled opportunity for mere mortals to experience life and the majesty of the unforgiving arctic wilderness, if only for as long as those mere mortals can tolerate it.

– A moral-sapping quote on display in the Svalbard Museum, Longyearbyen

Towards the very top of the Northern Hemisphere, about as human as the High Arctic gets and one of the world’s most adventurous places to travel according to Rough Guides, this is realistically as far north as one can venture without being a scientist and the furthest north man has managed to settle permanent communities inhabited year-round. And while pack ice impedes access to the rest of the Arctic, the Gulf Stream keeps some of Svalbard continually ice-free enabling year-round settlement and tourism. People can live the Arctic here. They can experience it, understand it. Yes of course it’s out of the way, and no it’s not a location for the dilettante traveller, but it’s (relatively) straightforward to get here (just get yourself to mainland Norway, itself hardly a reserve of the avant-garde adventurer, for the onward flight) and, with a bit of savvy planning, not as expensive as you might think.

The Miners’ Memorial in ‘downtown’ Longyearbyen, a bronze statue depicting a miner in lomp, as miners garb was known. Honouring those who worked (& died) the Longyearbyen mines and helped to shape the Longyearbyen of today, it was unveiled in 1998 by Olav Theodorsen, a miner who worked the Longyearbyen mines for almost 4 decades (1960-1998). Longyearbyen, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 24, 2018.

3 Seasons

The locals say there are 3 seasons here – day, night & snowmobile season. Below freezing for 8 months of the year, the average low temperatures during the winter (November to February, the Dark winter, and March to mid-May, the Light/Sunny Winter) routinely drop below -15 °C (5 °F) and in no month does the average monthly temperature exceed 10 °C (50 °F).

Joker. An Alaskan Husky. Pre-mush. Day 2. March 21, 2018.

The Long Polar Night & Midnight Sun

Svalbard is one location that doesn’t take the atmospheric phenomena that is the setting & rising of the sun for granted. It can’t possibly. From sunset in late October until the sunrise in mid-February, there’s constant darkness, the so-called Long Polar Night where the sun remains stubbornly a full 8° below the horizon. And the sun never sets over Longyearbyen, the so-called Midnight Sun, between April 20th & August 23rd. That, if you’re counting, is 126 days of continuous light.

– A quote on display in the Svalbard Museum, Longyearbyen

My ride. Snowmobiling. Day 3. March 22, 2018.

– Hans Engebretsen

Marvelous March

I’d have a hard time imagining that wilderness experiences when visiting Svalbard, and regardless of the time of year, are anything but otherworldly (yes, even during the Long Polar Night, the obvious best time of year to be dazzled by the Aurora Borealis, a.k.a. the Northern Lights). That said, visiting now, in late March during the so-called Sunny Winter, ensures the best of both Arctic worlds; the landscape is still an Arctic winter wonderland and the light has returned from its winter hibernation to allow you appreciate the wondrous environs (and there’s a full 12+ hours of light to boot, the sun rising today at 05:52 and setting at 18:21). Spring energy levels are up and everyone wants to get outside (this is prime snowmobile & dogsledding season) as Svalbard warms up for its annual party piece, its astonishing transformation from a dark, silent & frozen winter wasteland to a land of rich tundra where small flowers blossom, winsome wildlife wander & a rush of bird life returns. It’s a natural ugly duckling act matched nowhere else on earth, a transformation highlighted in this BBC documentary the viewing of which some months ago saw me booking this trip to Svlabard on something of a whim, obviously enticed by what I saw. I couldn’t think of a better time to visit (but I would say that). I timed my visit well, and not coincidentally of course.

Trestles from the cableway leading to Mine 6 & Mine 5 in Advantdalen (Advent Valley), Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 22, 2018.

Arctic Wilderness

For obvious reasons, the majority of the few travellers who venture up to Svalbard base themselves in Longyearbyen, me included. I’ll get back to highlighting Longyearbyen anon; its position, resting in a valley on the shores of Advent Fjord & hemmed in by snow-capped craggy peaks, goes someway to compensate for its industrial forlorn look & feel. It’s unique location yes, but unique can be ugly too (although, and as it always does, a blanket of snow helps with the town’s aesthetics this time of year). Of course Longyearbyen’s biggest plus is its gateway status to the surrounding wilderness of the High Arctic environment, one of Europe’s very last pure wilderness areas where you can experience Arctic nature at its rawest and most powerful. And needless to say with tourism in full swing here, the options for arctic exploration are legion – snowmobiling, ice cave exploration, glacier hikes, dogsledding, boat trips/cruises, wildlife safaris, tours of abandoned coal mines etc. Any one of these activities will likely induce cryopathy while all will put a noticeable dint in your pocket, but they’ll also get you out amongst all that will awe while also helping to stave off ‘island fever’, as the locals call being stuck in Longyearbyen. And who knows, in the process you might even sight a resident polar bear (preferably from afar, of course), arctic fox, Svalbard reindeer (a peculiar short-legged species unique to the archipelago), seal or walrus. Regardless of what you do in and see of the Svalbard wilderness, you gotta do and see it. Experiencing the untouched Arctic. It’s what being here is all about.

– From The Governor of Svalbard’s ‘Safety In Svalbard’ pamphlet.

So yeah, you really gotta love wilderness to come here, not to mention the cold (outside of the summer). There’s little else. It’s 62,000 km² of nothingness. The vast emptiness, the blinding whiteness, the calming soundlessness & the biting cold. They all emphasise the absolute nothingness of this shivering land, as does the realisation, always in the back of your mind, that humans, weak in such an environment, probably shouldn’t be meddling here. Wilderness rules on Svalbard and no mistake, even here among the modern comforts of Longyearbyen – an avalanche in December 2015 in the town killed two and a February 2017 avalanche required the evacuation of some 200, both events demolishing numerous buildings.

Snowmobiling past the distinctive & colourful ‘pointy houses’ of Longyearbyen, some of which were demolished by the 2015 & 2017 avalanches caused by the buildup of snow on the slopes of Mount Sukkertoppen rising up behind the structures and overlooking the town. Longyearbyen, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 23, 2018.

– From The Governor of Svalbard’s ‘Safety In Svalbard’ pamphlet.

Svalbard Schedule

I’ve a busy itinerary here on Svalbard in a bid to soak it all up and get an appreciation for what’s out there. It starts in earnest tomorrow, Day 2, and tentatively looks as follows:

Day 1 – Arrival

DAY 2 – Dogsledding to an Ice cave

DAY 3 – Snowmobile to Barentsburg

DAY 4 – The Longyear Valley & Longyearbyen

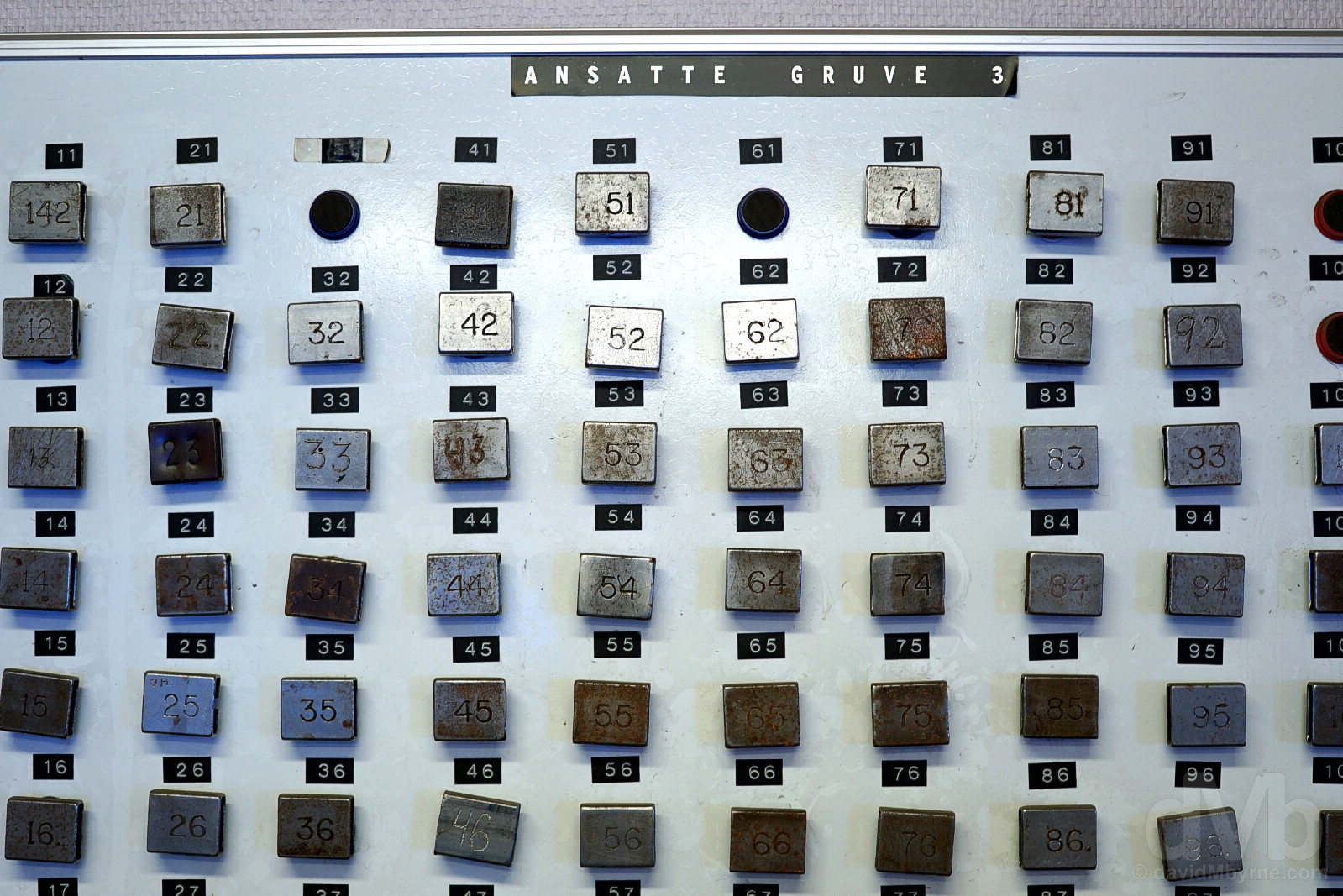

DAY 5 – Longyearbyen Surrounds (Mine 3; Global Seed Vault; Mine 7, Adventdalen & EISCAT; Hotellneset; Svalbard Bryggeri (Brewery))

Day 6 – Departure

Best get some sleep. I’ve a busy few days ahead.

dMb's (Kingdom of) Norway Overview

(Kingdom of) Norway

(Kingdom of) Norway

Region – Scandinavia & The Arctic (dMb tags: Scandinavia & The Arctic). Capital – Oslo. Population – 5.2 million. Official Language – Norwegian. Currency – Norwegian Krone (NOK). GDP (nominal) per capita – US$73,000 (world’s 3rd highest). Political System – Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy. EU Member? – No (but thanks for the offer, twice). UN Member? – Yes (founding member admitted November 1945). G20 Member? – No. Size – 385,000 km² (Europe’s sixth-largest country is slightly smaller than neighbouring Sweden, approximately twice the size of Syria & half the size of Chile). Topography – Largely mountainous high terrain with an extensive rugged coastline on the western edge of the Scandinavian Peninsula liberally dotted with massive Ice Age-era fjords, not forgetting the High Arctic archipelago of Svalbard. Climate – Mild summers, bone-chillingly cold & dark winters. Brief History & Today – There is evidence of occupation along coastal Norway stretching back to the 11th millennia BC. The Vikings, those raiding & trading Norse seafarers, spread out from Scandinavia to terrorise much of northern Europe between the 8th & 10th centuries, the Viking Age. The Black Death of 1349, the epidemic form of bubonic plague that killed nearly half of the population of Western Europe, killed an estimated 60% of Norway’s population & plunged the country into a period of economic & social decline. Weakened Norway eventually entered into a union, the Kalmar Union, in 1397 with Sweden & Denmark, the three Scandinavian kingdoms first ruled by a single monarch, Eric of Pomerania. Sweden left the union in 1521 and although Norway tried to follow suit, it didn’t succeed in breaking from the union with Denmark until 1814 when the Danes were forced to cede Norway to Sweden as a result of defeat in the Napoleonic Wars. Following this Norway promptly tried to declare independence, a move resisted by Sweden. Independence eventually came in 1905. Neutral in principle during both World Wars, the country was nevertheless invaded by the Germans in April 1940. Oil was first discovered in the mid-1960’s marking the start of a decades-long state investment in the country’s petroleum industry, the economic benefits of which the country enjoys today and which makes Norway one of the world’s wealthiest countries. Rejecting EU membership not once but twice (in 1972 & 1974), today Norway is a progressive society with one of the world’s highest standards of living and with possibly the most developed and stable democracy and state of justice in the world. UNESCO World Heritage sites – 8. Tourism Catchphrase/Slogans – Powered by Nature. Famous For – Fjords; glaciers; having an abundance of natural resources; wilderness; winter sports; being rich & a shockingly expensive destination in which to live and visit; being political stability & for topping many international socio wellbeing indices (Human Development Index, the Better Life Index, World Happiness Report, Index of Public Integrity, Democracy Index, Press Freedom Index etc.). Highlights – The outdoors & the wondrous wilderness – dramatic jaw-dropping landscapes abound with the fjords of coastal mainland Norway considered one of the world’s top tourist attractions and the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard the planet’s most accessible region for exploring the majestic but unforgivable High Arctic. Norway Titbits – Boasting extensive reserves in oil & gas, Norway is the world’s largest per-capita oil & natural gas producer outside of the Middle East, the petroleum industry accounting for one-quarter of the country’s vast GDP; not short of a krone or two, the country boasts the world’s largest sovereign wealth/rainy day fund, an estimated USD $1 trillion; stretching from 57° to 81° N (north of the equator), Norway’s jagged & fjord-infused mainland, together with its thousands of islands, boasts a coastline of over 25,000 kilometres; the high latitude and large latitudinal range of the country also means it has a vast variation in topography, climate and large seasonal variations in daylight – for 2+ months in the summer in the High Arctic the sun never completely descends beneath the horizon, hence Norway’s tag as the ‘Land of the Midnight Sun’.

Visits – November 2012 (Oslo) & March 2018 (Svalbard).

– Lonely Planet

Svalbard, Norway

DAY 2 - March 21 2018Dogsled. Waiting to mush. Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway.

“We mushed home, the dogs not sparing any horses on the mostly downhill return, seemingly their favourite part of the day. It was probably mine too, although trying to capture pictures & video while sporting bulky gloves and while simultaneously trying to remain precariously perched on the back of a speeding sledge and keep acceleration in check is, I suspect, not how I was supposed to pass the time.”

Day 2 – Dogsledding

Dogs have been used to pull sledges in certain regions of North America for at least a thousand years, and even further back in regions such as modern-day Siberia where it’s thought they were using dogs for this purpose as much as three millennia ago. The environmentally friendly rival to snowmobiling and an iconic Arctic must-do, the soundtrack of huskies barking as I mushed through the crisp stillness of the pristine Arctic wilderness will be both the highlight of today, day 2, and an abiding memory of my time on Svalbard.

Dogsled. Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 21, 2018.

Mushing

Mushing is fun. The hardest part is probably fending off frostbite at the extremities, especially the fingers, while trying to remain on the sledge, the most important part counteracting huskie eagerness by 1) feathering the break to keep the line taut and avoid rear-ending them & 2) remembering to apply the break when stationary (to prevent them taking off). Obviously the huskies do all the work, the progress of the dogsled altered if need be by shrill cries from the musher, to which the huskies seem to react instinctively. The musher has no need to crack a whip (doesn’t even carry one), and nor do they need to holler “Mush, mush!!” to get the dogs going. Very little encouragement is needed – the amazingly tough little Alaskan huskies, working in unison, are chomping at the bit and never seem to tire of the task at hand, although they obviously toil when encountering a hill. As always, the descents are much easier (& a lot more fun), but either way the dogs earn their snacks.

Alaskan husky. Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 21, 2018.

Husky Travellers

While multi-day sledding trips are available, most seem content with a 4-hour or day-long dogsledding excursion. It’s a competitive business among sledding providers, all of which seem based on the edge of Adventdalen (Advent Valley) on the outskirts of Longyearbyen. I lost my mushing virginity to Huskey Travellers, a small family-based operation with both a personal touch and personable guides. Having free reign of the yard, I was afforded plenty of time with the friendly dogs, including pre-mush when they were still snug in their raised kennels.

Joker, pre-mush. Husky Travellers, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 21, 2018.

‘Real Taste – Real Energy’ Lunch & Ice Cave

We mushed (uphill) to the end of a valley. The dogs had a well-earned rest (& snack) while we had a DryTech ‘Real Taste – Real Energy’ just-add-boiling-water lunch out of a foil packet while sitting in a snow hole cum outdoor Arctic diner. I opted for the Chilli con carne, doubtless my spicy freeze-dried stew & coffee would have tasted as good if not for the novelty of the moment &/or the surrounds. We then explored an ice cave. Its tight confines were warm, so much so that cameras fogged up. Thus memories of walking inside a massive age-old ice cube are cranial ones now, not digital (while a memorable endeavour, it was far from a photogenic one). Exiting the cave, some had to answer the call of nature. Thankfully I didn’t.

Answering the call of nature at the entrance to the ice cave. When you gotta go you gotta go, although it’s a rather inconvenient exercise in this environment and when sporting a bulky snowsuit, especially for females. Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 21, 2018.

The Return

We mushed home, the dogs not sparing any horses on the mostly downhill return, seemingly their favourite part of the day. It was probably mine too, although trying to capture pictures & video while sporting bulky gloves and while simultaneously trying to remain precariously perched on the back of a speeding sledge and keep acceleration in check is, I suspect, not how I was supposed to pass the time.

Mushing home. Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 21, 2018.

Day 2 Gallery

The complete gallery of captures from today.

Baggage Arrival & COOP Grocery Shopping

Mercifully, my bag arrived while I was out mushing meaning I was reacquainted with my winter warmers and sufficiently wrapped up when embarking on a trip to the grocery store this evening to pick up a few essentials.

GROCERY SHOPPING || Grocery shopping. COOP, Longyearbyen, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 21, 2018.

Shopping of any kind in Longyearbyen is likely to quickly descend into an exercise in financial damage limitation, and that even goes for a trip to the COOP, a well-stocked supermarket & the only grocery store in town. If you know anything about Svalbard pre-arrival you’ll probably know it’s not a cheap place to visit – everything needing to be imported (& most waste exported) means prices are high, especially for perishables – but a trip to an everyday-normal grocery store will quickly educate as to just how high the prices are. Use a Debit Card (in 6 days on Longyearbyen I never once used cash); the outlay of NOK95 beers (€10/US$12) didn’t seem to sting as much that way.

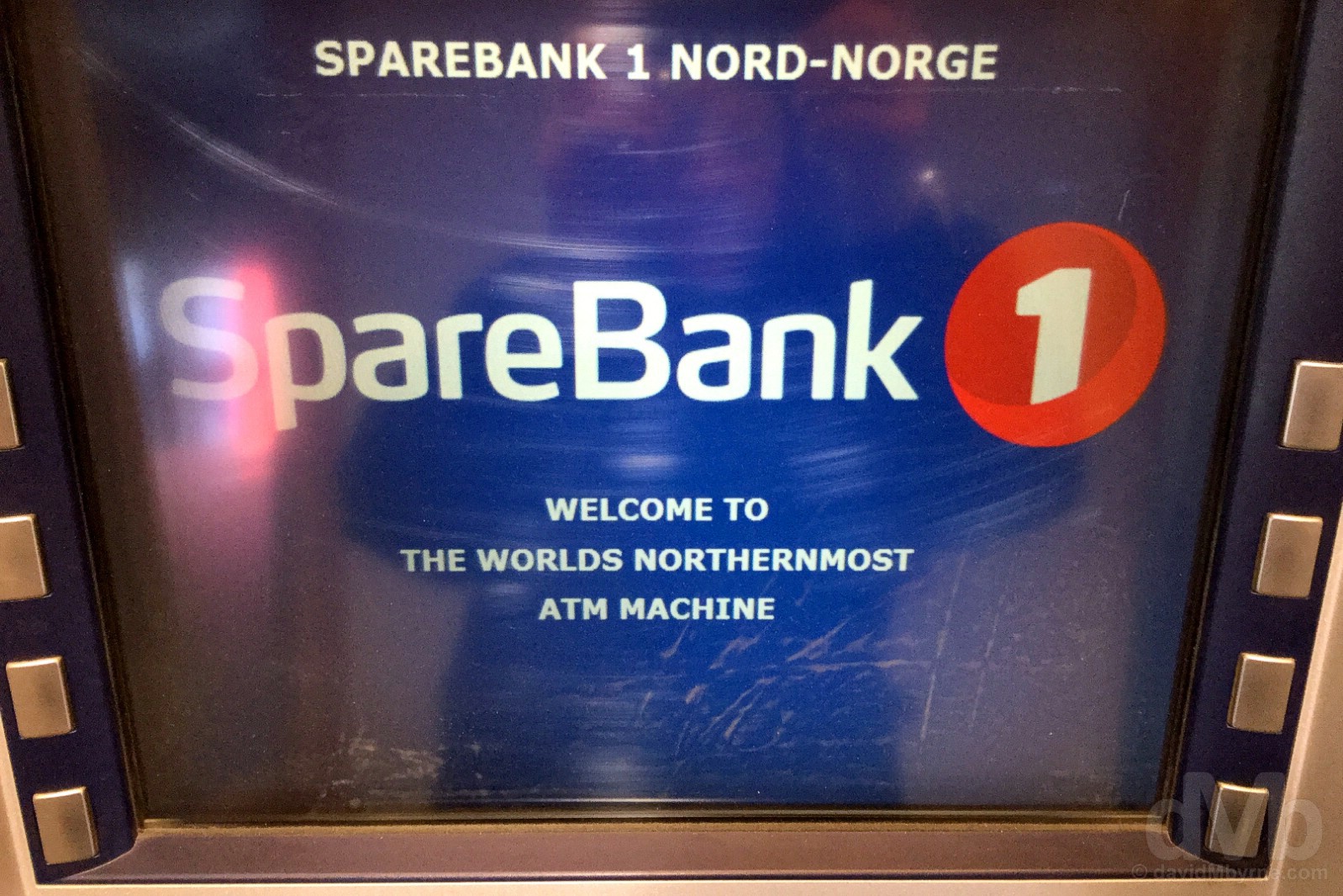

NORTHERNMOST ATM || Should you need cash there’s always the world’s northernmost ATM. Longyearbyen, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 24, 2018.

Svalbard, Norway

DAY 3 - March 22 2018Snowmobile. Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway.

“Svalbard is one of the last remaining areas of unspoiled wilderness in Europe. There are huge tracts of relatively pristine nature outside the few human settlements. And with no roads connecting them, the snowmobile… is the de facto way to hied from A to B. And doing so is a whole lot of bombilating fun.”

Day 3 – Snowmobiling & Barentsburg

Svalbard is one of the last remaining areas of unspoiled wilderness in Europe. There are huge tracts of relatively pristine nature outside the few human settlements. And with no roads connecting them, the snowmobile, called snow scooters on Svalbard and Skidoos in North America, is the de facto way to hied from A to B. And doing so is a whole lot of bombilating fun.

Pit stop. Snowmobiling on Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 22, 2018.

– From The Governor of Svalbard’s ‘Animal safety is your responsibility’ pamphlet

PRISTINE & (RELATIVELY) UNTOUCHED || A portion of the island of Spitsbergen as captured from on high en route from Longyearbyen to Barentsburg. Svalbard, Norway. March 22, 2018.

It seems the only thing that disturbs the placidity of the arctic wilderness on parts of the island of Spitsbergen is the drone of a snowmobile convoy, their tracks one of the very few scars on the otherwise untouched landscape.

– From The Governor of Svalbard’s ‘Help Preserve Svalbard’s Wilderness’ pamphlet

One needs a driver’s license to operate a snowmobile (it’ll be checked), can’t be under the influence and must wear a helmet and be properly suited up – skin shouldn’t be exposed as frostbite is a real concern when speeding through -14 °C (7 °F) temperatures at 70 km/h, the most I could get out of my 600cc BRP Lynx Adventure LX ride, a whole 10 km/h shy of the 80 km/h speed limit in force outside of Svalbard settlements.

Snowmobiling on Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 22, 2018.

Operating a snowmobile is as easy as falling off a log on flat terrain (simply push a button, pull a lever and – Yahoooo! – off you go), but snowmobiles can be tricky to operate at high speeds and on difficult terrain, something you’ll rarely encounter if your guide deems any of the team not up to the challenge.

– Excerpt from The Governor of Svalbard’s Safety in Svalbard pamphlet

ISSUES || Follow the leader. Always. Snowmobiling on Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 22, 2018.

Snowmobiling issues, when they do arise, can be attributed to uneven and sloping terrain, little of which you’ll be subjected to if your guide, who, and as seen here, always leads the convoy and pulls the necessary safety equipment & spare parts, wants to avoid any potentially news-worthy or life-threatening incidents – the Svalbard wilderness isn’t a place to be stranded. Most issues, as rare as they are, are weather related – snowdrifts, wind holes (holes on the snow created by the wind), fog and blowing snow. Icy goggles/visors, flat-light (an absence of shadows or gradients of light to help define terrain outlines) and white-outs (blinding brightness) don’t help either, any one of which can quickly make orientation difficult. No such problems today, a beautiful day here zipping across Spitsbergen to and from Barentsburg.

Day 3 snowmobiling destination. Black smoke from the towers of the coal power plant as seen from the outskirts of the Russian coal mining settlement of Barentsburg. Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 22, 2018.

Barentsburg – Little Russia

Our destination for today was the Soviet-era Russian coal mining settlement of Barentsburg, 55 kilometres west of Longyearbyen and now the only Russian coal mining interest left on Svalbard following the 1998 closure and abandonment of the Russian mining settlement of Pyramiden, my first choice as a snowmobiling destination but somewhere that is presently not accessible – there’s not enough ice/snow to access Pyramiden via snowmobile but still too much ice to allow access by boat, or so I’ve been told. First settled as a Dutch mining town in the 1920s and named after Dutch explorer Willem Barentsz, Barentsberg is Svalbard’s second-largest settlement with a population of about 420 (down from over 1,000 in its heyday), almost all of which are young & healthy male Russians and Ukrainians on 6-month to 2-year mining contracts – the average residency in Barentsburg is 4-5 years, although stays are getting longer, especially for those miners who have their families with them.

LENIN STATUE || The Barentsburg landmark, the second-most northerly Lenin statue in the world. Barentsburg, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 22, 2018.

While Pyramiden and its eerily abandoned unique arctic ghost town vibe was my first choice for a snowmobiling jaunt out of Longyearbyen, Barentsberg served as an able backup. Having researched this location prior to arrival, I stood at the base of this statue in the centre of Barentsberg surveying the tiny settlement I’d previously viewed online. It was awesome, the settlement’s farawayness palpable.

COAL || Coal, the reason there’s anyone here at all. Outside the mine in Barentsburg, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 22, 2018.

A coal truck in Barentsburg, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 22, 2018.

Barentsberg – History & Mining

The Russians bought Barentsburg from the Dutch in the early 1930s with the Russian state-owned Arktikugol (Arctic Coal), a company formed in 1931 to administer all Soviet mining interests on Svalbard, taking over the Barentsburg mine in 1932. Kept in state hands following the early 1990s post-USSR privatisation of the rest of Russia’s coal mining industry, there really is no economically viable reason for Barentsburg to exist in its present form as a mining town (it only exports some 100,000 tons of coal yearly). Low on reserves since the 1990s, producing poor quality coal and continuing the dodge the fate that befell Pyramiden (although only just – Barentsburg ceased mining between 2006-2010 citing mine safety issues), to continue mining on Svalbard these days is nothing more than a matter of principle and a presence here a political imperative for Russia.

MINERS MURAL & SCHOOL || The Miners Mural and school building off ulitsa Ivana Starostina, the main street in Barentsburg, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 22, 2018.

ABANDONMENT & DECAY || Abandonment in Barentsburg, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 22, 2018.

The population of Barentsburg has been steadily decreasing in recent years. There’s something of a forlorn, lost colony feel to the place, a large swathe of buildings sitting uninhabited/unused, many simply left to decay.

SETTING & ISFJORD || A colourful wooden building overlooking Isfjord in Barentsburg, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 22, 2018.

Looking inland, Barentsburg is a rather unsightly settlement given its coal mining scars – it’s essentially a town built on a hillside and around a coal mine. Things are less of an eyesore when looking in the opposite direction. Barentsberg’s setting overlooking Spitsbergen’s Isfjord, the second longest of all of Svalbard’s fjords, and especially on a clear day like today, is nothing short of stunning.

WOODEN ORTHODOX CHURCH || The small orthodox church overlooking Isfjord in Barentsburg, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 22, 2018.

Barentsburg’s small & poignant wooden orthodox church was erected in 1996 to commemorate the 141 victims of Vnukovo Airlines Flight 2801, a charter flight from Moscow that crashed on August 29 of that year while on approach to Svalbard. The flight, which was bringing in a new shift of workers to the mining communities of Barentsburg & Pyramiden, is still the deadliest aviation accident in Norwegian history, the disaster often cited as the catalyst for Arktikugol’s 1998 closure of Pyramiden.

WOODEN ORTHODOX CHURCH || The interior of the wooden orthodox church in Barentsburg, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 22, 2018.

Not really sure where I should and shouldn’t venture in Barentsberg saw me exploring somewhat sheepishly. I was presently surprised to find the church open, a welcome respite from the arctic chill provided by the warm & tight interior – you’d scarcely fit a dozen people in here with no seating of any kind, a feature of a Russian Orthodox Church. I only noticed upon exiting the signs that requested the door to be kept closed at all times (not locked, just closed) and that the exterior bells are only to be rung once in possession of a blessing from a priest. I didn’t have the latter and with the odds of finding a priest in the almost deserted settlement rather slim I was unable to break the Barentsberg silence – its was an eerily quiet yet fascinating place to explore.

Barentsburg – Company Town to Burgeoning Tourist Location

Barentsburg is a true company town, much like the Longyearbyen of old. Everything you see here, from the houses to the shops to the administrative buildings to the church, and be they crumbling or new, belong to Arktikugol; the present-day Barentsburg Hotel, recently renovated in 2012, resulted from the conversion of a residential apartment building in a failed attempt to diversify the economy. At least so far. Tourism is picking up the world over, forlorn Barentsburg on far-flung Svalbard being no exception. Tourism doesn’t yet generate enough income to revive the town, but they are making an effort to appease those who make the effort to visit and, it seems, people are coming. I’m here. Enough said.

MINING & POLAR BEARS || Barentsburg. Mining & Polar Bears, a tourism catchphrase maybe. Lunch in the Barentsburg Hotel, Barentsburg, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 22, 2018.

We had lunch in the empty but spotless dining room of the Barentsburg Hotel, spruced up after its recent renovation and just crying out for patrons. The food and coffee was awesome, although some of the thinly sliced meat a mystery – even our guide wasn’t sure if it was whale, reindeer or something else altogether. The whole experience was as Russian as you can get, exemplified by the impersonal service provided by the surly young waitresses. The only Russian stereotype absent was a death stare or two from a gold-toothed, purple-haired babushka (an elderly Russian or eastern European woman) – needless to say, and just like on the rest of Svalbard, you’d be hard pressed to find anyone of advanced age, or poor health, in Barentsberg.

VODKA || Vodka in the bar of the Barentsburg Hotel, Barentsburg, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 22, 2018.

No issues, however, finding vodka in Barentsberg, the bar of the Barentsberg Hotel displaying a rather nice Svalbard-inspired selection of Russia’s signature tipple (who drinks this stuff I wondered to myself in the empty bar). There was even a version boasting a ABV of 78%. ’78° – Spirit of The Arctic’ vodka, its logo a polar bear with its head in the snow, claims Soviet-era polar explorers demanded a drink with an alcohol content that matched the latitude. Shots in here go for NOK60 (€6.20/USD$7.70), rather cheap for Svalbard. Indeed, Barentsberg, which even boasts a tiny brewery, serves up what might very well be the world’s rarest beer and, at NOK20 (€2+/USD$2.50+), possibly the cheapest brew in all of Scandinavia.

HOMEWARD BOUND || Approaching the settlement of Longyearbyen as seen from Longyearbreen (the Longyear Glacier) above Longyeardalen (the Longyear Valley) in Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 22, 2018.

Our guide was impressed with our pace and driving which enabled us to take a longer route home over more difficult terrain. The ultimate reward was an awesome perspective of Longyearbyen as seen from Longyearbreen (the Longyear Glacier) leading down to Longyeardalen (the Longyear Valley). We stood here for a while peering down over the settlement sitting in the lower portion of the valley on the shores of Adventfjorden (Advent Fjord) and at the foot of the mountains of Platåberget (left) and Gruvefjellet (right). In the distance, across Adventfjorden, is the unmistakable hulking form of Hiorthfjellet. Probably Svalbard’s most photographed natural landmark, at 928 metres (3,040 feet) it is the highest peak in the immediate vicinity of Longyearbyen and to see it soaking up the last of the day’s rays at the end of a 130-kilometre arctic snowmobiling adventure was to prove a memorable welcome home.

Day 3 Gallery

The complete gallery of captures from today.

Svalbard, Norway

DAY 4 - March 23 2018The colourful ‘Pointy Houses’ of Longyearbyen, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway.

“Established as Longyear City (Longyearbyen in Norwegian) in 1906 by American John Munro Longyear as a coal mining town with a spattering of rudimentary wooden buildings and a handful of hardy souls, Longyearbyen is the capital of Norway’s Arctic Svalbard Archipelago and, with a population of 2,100+, by far its largest settlement.”

Day 4 – Longyearbyen & The Longyear Valley

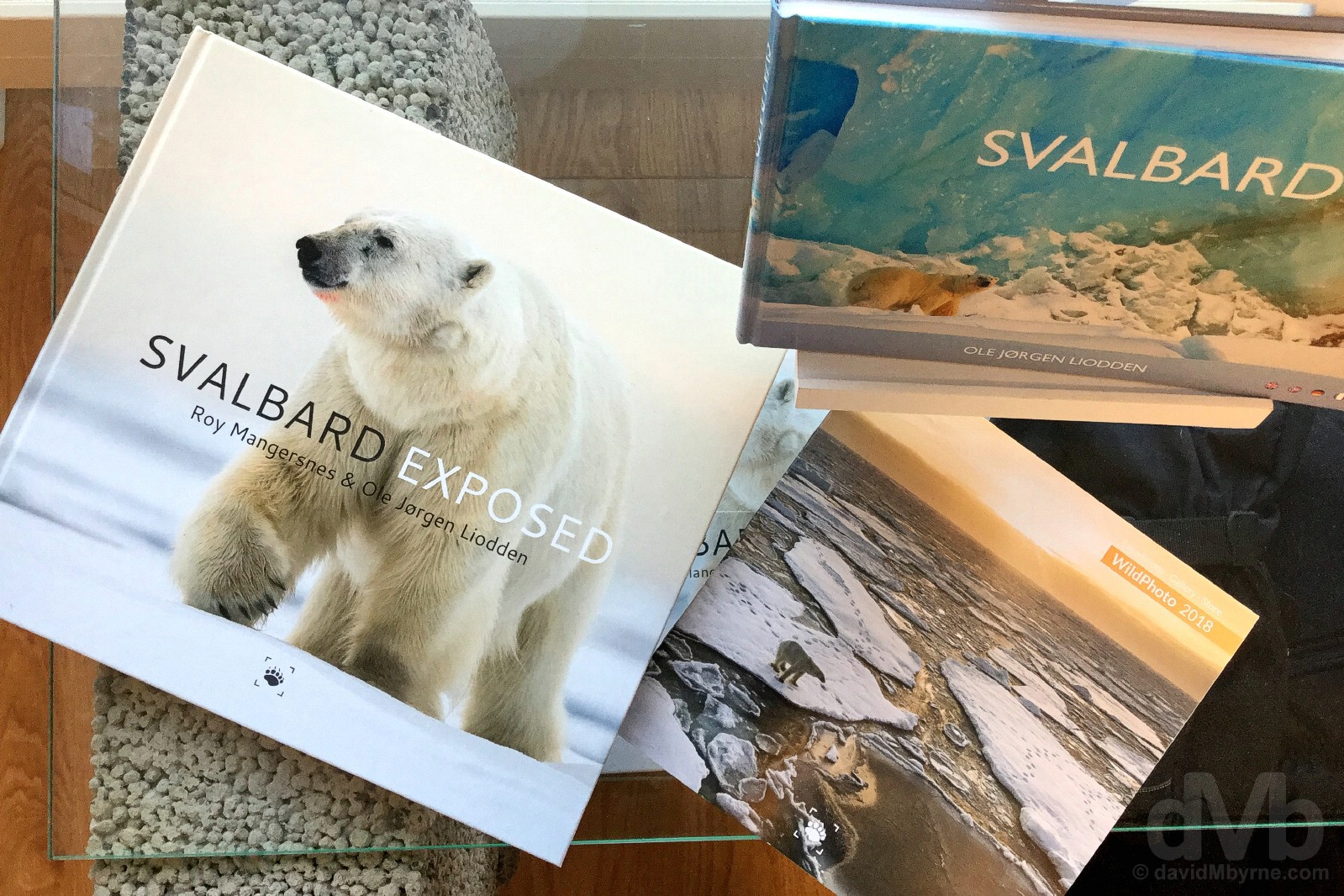

I‘m well aware of the potentially fatal consequences, but still. Today I – shuuu! – broke the Svalbard rules. Well, one of them at least. I briefly exited the safe zone unarmed, foraging a bit too far up the Longyear Valley for an impressive overview of Longyearbyen (and to peak into an abandoned coal mine). And not counting long-since-dead ones stuffed & harmlessly on display in both the Svalbard Church and the impressive Svalbard Museum, or pictures of them in the town’s Wild Photo Galley, I didn’t encounter any polar bears on a cold day Day 4 (& freezing night), a day finally spent getting a closer look at Longyearbyen and its immediate surrounds.

Overlooking Longyearbyen, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 23, 2018.

Signing off for day 4. It was an effort tonight to scale the steep & icy valley slopes of Sverdruphamaren to get a vantage point overlooking Longyearbyen. The mercury was reading -15 °C (5 °F), to say nothing of what it felt like allowing for the windchill (at times the Longyear Valley the town sits in acts like something of a wind tunnel). Needing to adjust camera settings necessitated me dispensing with my gloves. My fingers stopped working for a while – numbness, just prior to the onset of frostbite, is the warning sign – but my camera didn’t miss a beat.

Longyearbyen

Established as Longyear City (Longyearbyen in Norwegian) in 1906 by American John Munro Longyear as a coal mining town with a spattering of rudimentary wooden buildings and a handful of hardy souls, Longyearbyen is the capital of Norway’s Arctic Svalbard Archipelago and, with a population of 2,100+, by far its largest settlement. The only town to be incorporated in the Norwegian Arctic, the settlement is the seat of The Governor of Svalbard and the northernmost community on planet earth with 1,000+ inhabitants, or as some claim the northernmost ‘real’ town on earth. Whatever it may be, Longyearbyen, and no mistake, looks & feels every bit the forlorn outpost that it is.

The settlement of Longyearbyen, resting in the lower reaches of the Longyear Valley and by the shores of Adventfjorden (Advent Fjord), and the hulking peak of Hiorthfjellet as seen from the upper Longyear Valley, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 23, 2018.

Laid out in a grid style in an almost straight line from the old dock on Adventfjorden, the first cableway and a crude 1,250-metre-long railway were constructed in 1906 to connect Svalbard’s very first coal mine, Mine 1a, a.k.a. the American Mine (opened 1906, closed 1920), in the mountainside above the ruins of Old Longyearbyen (left, with the pointy Svalbard Kirke (Svalbard Church) in sunlight), to the dock. Mining-related expansion continued and by 1913-1914 over 240 people were overwintering in Longyearbyen, all mining company employees. Eventually the first buildings not related to mining were constructed (a church in 1921 and a post office & school in the mid-1930s) with the settlement beginning, after World War II, a slow and inexorable transformation from company town – where everything is owned, operated and overseen by the mining company – to a locally governed community with modern amenities (fully fledged local democracy wasn’t implemented until the 2002 creation of the 15-elected-member Longyearbyen Community Council). In the space of the last 25 years, Longyearbyen has transitioned from an autocratic, government-subsidised company coal town to a vibrant, democratic tourist destination and major Arctic research hub with a population of over 2,000 thanks, in part, to favorable income tax breaks for residents.

– Peter Adams

NORTHERNMOST WHATEVER || Looking up the Longyear Valley from ‘Downtown’ Longyearbyen, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 23, 2018.

Longyearbyen is a quirky, vibrant town with no street names, only numbers, one where reindeer routinely amble freely in the streets. It features a few kindergartens; a primary school with secondary education facilities; a university; bus transport (albeit only to & from the airport); a cultural house cum arts & crafts centre with a cinema, a café & a library; a sports hall; a swimming pool; a gallery; a youth club; a hospital; a post office; and a few museums & galleries. Of course anything found here is more than likely the northernmost whatever on the planet; Longyearbyen likes to boast that it has the northernmost commercial airport, department store, church, fire station, bar, car dealership (Toyota), ATM, gas/petrol station, full-service hotel (a Radisson) and gourmet restaurant (Huset) on earth.

COMPANY CAMP TOWN || Buildings of Longyearbyen, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 23, 2018.

Most of present-day Longyearbyen was built after World War II (yes the war even reached up here, a German attack on September 8 1943 levelling much of the then Longyearbyen), a time when the settlement expanded greatly with the 1945 resumption of mining operations and/or the opening of new mines. Most residents inhabit the settlement’s small colourful wooden houses, abodes that are propped up on stilts, or piles, to prevent flooding and sinking by keeping the structures removed from the upper active layer, the layer sitting above the permafrost that melts each summer as the temperatures rise above freezing. The buildings are typical of the temporary nature of mining towns – they are long and low, similar to barracks, or they are terraced and linked small houses with attached storerooms. There are very few freestanding houses and the outside areas are generally empty except for grit boxes and parked cars and snowmobiles – there are no gardens, sheds or garages and houses are not surrounded by fences. All of this gives Longyearbyen the distinctive air of being a camp, a place for temporary residency as opposed to being somewhere where people intend to live for a long period of time. The fact that Longyerabyen’s roads are numbered rather than named also adds to the temporary camp nature of the settlement.

Svalbard - Coal & Mining

There would have to be a good reason for man to settle here on forlorn, quivery Svalbard in the first place, that good reason proving to be coal, Svalbard’s very own black gold. The archipelago’s hills, and even after a century-plus of mining, are still rich in coal deposits, and even though only token mining operations persist to this day, remnants of the mining past remain – rusting & fallen aerial tramways no longer in use and abandoned mines high up on scared mountainsides are never far away & never out of eyeshot.

Suspended for decades. Rusting coal buckets on a portion of the cableway system leading to the coal depot in Hotellneset. Longyearbyen, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 23, 2018.

– From The Governor of Svalbard’s Experience Svalbard on Nature’s own terms pamphlet

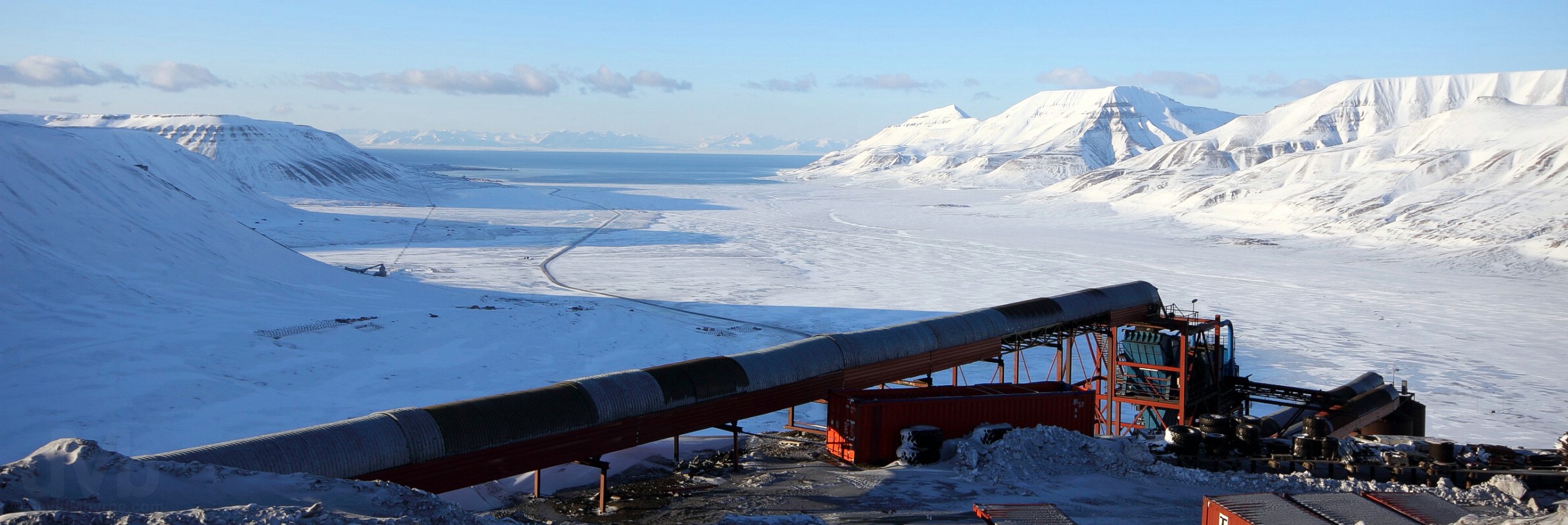

Although coal was found here as far back as 1610, scientific advances led to the 1899 discovery of abundant coal in the mineral-rich mountains of the archipelago. The early days of mining on this remote Arctic no man’s land were tough (many ventures failed, fortunes lost), but an industry eventually thrived, helped by the appetite for coal from newly industrialised Europe. While once a cornerstone industry, reduced coal prices (the price of coal dropped from USD$160 to USD$45 per ton between 2008 & 2016 making it too expensive to mine on Svalbard) and a socio-shift away from mining towards tourism and research means that today only two mines remain operational on Svalbard, one Russian (in Barentsburg) & one Norwegian (Mine 7), the latter producing coal to power Longyearbyen’s power station, Norway’s only coal-powered power station which produces hot water, heat and electricity for the town.

LONGYEARBYEN NEIGHBOURHOODS & MINE2B || Mine 2b on the slopes of Gruvefjellet as seen from the frozen Longyear river in Longyearbyen, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 23, 2018.

Longyearbyen today is a settlement of many adjacent neighbourhoods that sprung up with the opening of new coal mines at various stages throughout the 1900s – workers were always located as close to the mine as possible. The first neighbourhood was what is now called Old Longyearbyen below Mine 1a (opened in 1906, closed 1920). The town has since expanded up and down the valley and while the mines may have come & gone, the neighbourhoods remain. This is a picture of the spattering of buildings that combine to form the neighbourhood of Haugen. Established shortly after World War II, it is situated about a kilometre up the Longyear Valley from ‘downtown’ Longyearbyen and 1.5 kilometres down the valley from the neighbourhod of Nybyen (New Town), as far up the Longyear Valley as migration could & did go. Nybyen was established in the summer of 1946 with the construction of barracks for the workers of Mine 2b, a.k.a the Santa Clause Mine (opened 1937, closed 1968), seen here in the distance perched high on the steep slopes of Sukkertoppen. The largest of all mines in the vicinity of Longyearbyen, today the mine’s pithead and the long line of trestles of its cableway is still the most complete mining facility that has been preserved in the Longyear Valley – everything remains from the mining days except the boiler house and mine lift (to get workers from the valley floor to the pithead), both of which were demolished in 1986. Accessible in the past, today signs on the valley floor, by the side of the road running from the Longyearbyen waterfront and up the valley through Haugen to Nybyen, inform that the mine is ‘closed due to potentially unstable building elements.’ The sign also cautions any potential have-a-go hero not to ‘enter or go near the site’, one rule I was happy to abide by.

MINE 4 || Tracks leading to the abandoned Mine 4 in the Upper Longyear Valley, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 23, 2018.

Yes, I ventured further up the valley than I should have, beyond Nybyen to the tiny pithead of Mine 4 (opened 1966, closed 1970), the smallest mine and last to be worked in the Longyear Valley. A similar sign here warns not to enter the site, something scarcely possible given the boarded up nature of the pithead. It was the sense of calm and abandonment here that made the place as captivating as it was.

– From The Governor of Svalbard’s Experience Svalbard on Nature’s own terms pamphlet

PROTECTED CULTURAL REMAINS || A rusting railway sleeper bolt, a nondescript yet protected remnant from the past outside Mine 4 in the upper Longyear Valley, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 23, 2018.

As per the Svlabard Treaty, Norway is entrusted with the responsibility of preserving natural environment of the archipelago, and they are not shying away from the task. The Norwegian parliament – Stortinget – has determined that Svalbard is to be among the best managed wilderness areas on the planet, while at the same time there is a political wish to facilitate a sustainable tourism industry so that visitors can experience this marvellous but fragile environment for themselves, but only on nature’s own terms. In addition to environmental legislation, Svalbard also has special tourism regulations intended to protect the natural environment, its cultural monuments and the safety of those visiting. Specific tourism preservation regulations apply, among them the need to keep your grubby hands off ruins & rusting remnants of the past, old fragile treasures collectively termed ‘cultural remains’ – The Svalbard Environmental Protection Act protects as cultural heritage sites all traces of human activity pre-1946, everything from towering coal mining infrastructure to broken pots and pans to graveyard crosses to soles of shoes to bits of pottery. Essentially anything of age one may stumble across and all of which are well preserved by the cold, dry climate (for this reason, the area around Longyearbyen is littered with interesting artefacts including disused mining equipment, bits of rope and shovels, etc.). Oh, and the same hands-off rule applies to skeletal remains, be they human or animal – old slaughtering sites for walruses and whales dot the pristine Svalbard coastline.

– From The Governor of Svalbard’s When Visiting Svalbard – Information for Non-Residents pamphlet

CABLEWAYS || Abandoned cableway trestles, remnants of the coal mining past, on the slopes of Sverdruphamaren as seen from the Longyear Valley, Longyearbyen, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 23, 2018.

Old buildings, installations and equipment abound, but it’s the elevated cable car system, cableways, used to transport excavated coal that is easily the most striking example of cultural remains from the early mining activity that took place on Svalbard. Most of the mines in the vicinity of Longyearbyen are high up on steep, unstable mountainsides where it was impossible to build roads. This necessitated the need for cableways. Cheap and easy to build, move & extend, these long lines of towering trestles supporting cables that would carry heavy iron buckets of coal from the mines to the dock for shipping (in summer) or a depot for storage (in winter when fjord ice would prevent all shipping for up to 6 months a year). First built in 1906 and working via gravity (full, heavy buckets descending pulled empty, light buckets upwards), the long straight line of photogenic trestles seen here on the slopes of Sverdruphamaren were built in the 1930s to service Mine 1b. The last cableway was built in 1969 (to service Mine 6 opened that same year and closed in 1981) and by 1987 the cableway was servicing just one mine, Mine 7 (worked 1972-present), the last of the 10 mines to be worked in the vicinity of Longyearbyen since mining first started here in 1906. As it was not financially viable for the cableway to service just one mine, the whole system was closed that same year bringing an end to 8+ decades of cableway history – the cost of dismantling and shipping from here was often prohibitive, greater than the value of the infrastructure itself, so the cableway infrastructure has been left to slowly disintegrate, protected cultural remains showcasing a pivotal part of Longyearbyen’s mining history.

TAUBANESENTRALEN || Taubanesentralen (Cableway Central, left), Skjaeringa, Longyearbyen, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 23, 2018.

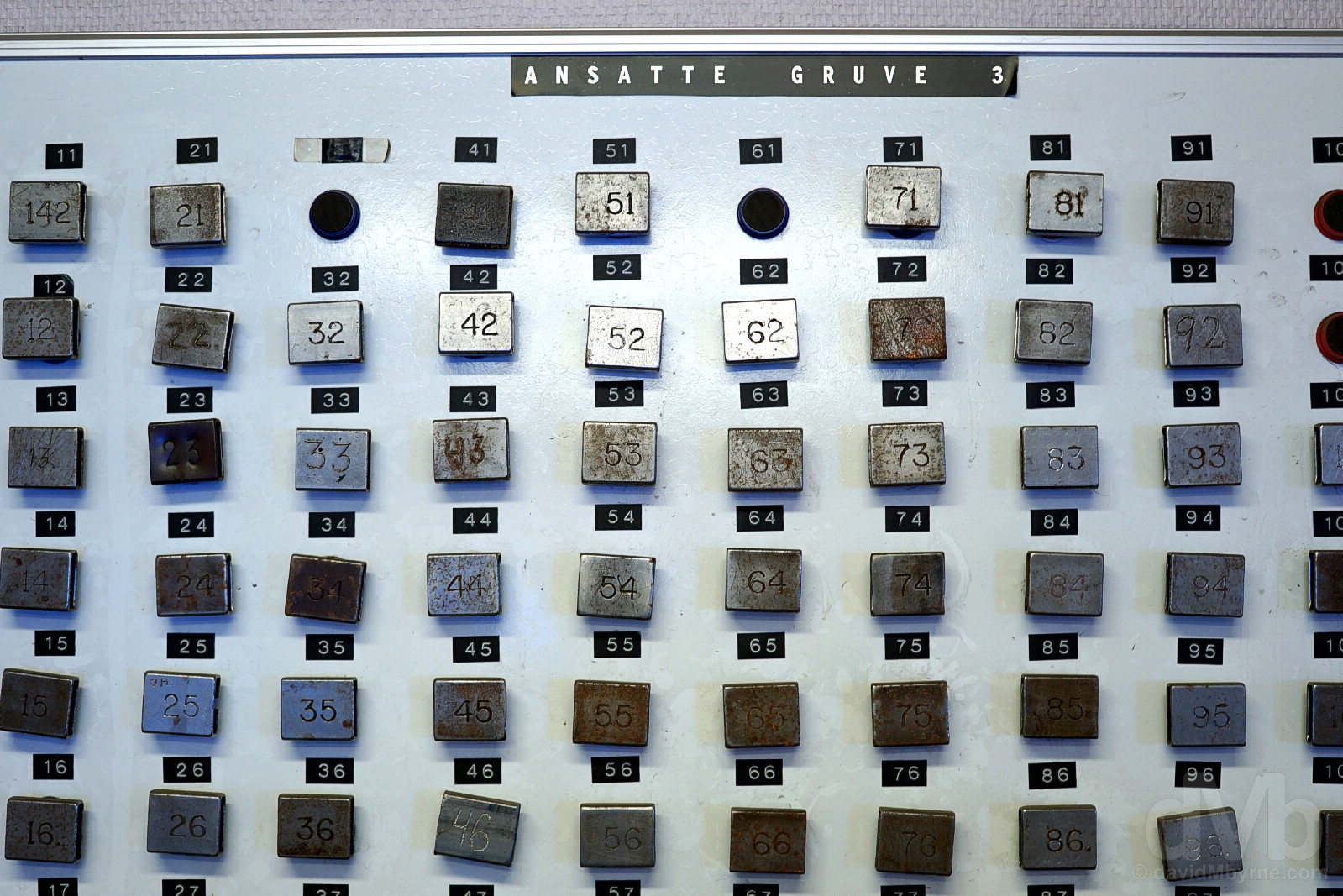

Never out of sight, the massive corrugated steel structure of Taubanesentralen (Cableway Central) looms large over Longyearbyen from its perch in the elevated Skjaeringa neighbourhod of the settlement overlooking Adventfjorden (Advent Fjord). The unsightly gray structure propped up on skinny legs is definitely the ugliest & probably the largest remnant from the mid-20th century mining activity that took place in and around the Longyear Valley. The nearest thing Longyearbyen had to a traffic management aid and acting like a railway station when busy, this was the nerve centre of the cableway with the co-called cableway general, the Taubanesentralen supervisor, deciding which mine would send its coal & to where it would be sent (to the dock or the storage depot). Long lines of trestles leading from here in several directions serviced the various mines, 6 in total after Taubanesentralen’s 1957 reconstruction following the German attack of 1943 (it was originally built in 1921). Today only one line of photogenic trestles with cables and buckets remain, heading northwest (left) away from Longyearbyen towards Hotellneset.

LONGYEARBYEN CEMETERY & THE 1918 SPANISH FLU PANDEMIC || The small cemetery on the lower slopes of Sverdruphamaren on the southwestern edge of Longyearbyen, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. March 23, 2018.

I’d read about Longyearbyen’s haunting little graveyard with simple white, wooden crosses pre-arrival and was fascinated to see it for myself. The final resting place for 34 Svalbard residents (a condition for burial here), it was established in early 1917 to bury two people who had died from illness; it also houses the remains of 4 miners killed in an explosion in Mine 1a, a.k.a. the American Mine, in 1919 (that lead to its closure a year later) and the remains of Captain Trond Astrup Vigtel, the commander of the Norwegian garrison in Longyearbyen that fell in battle during the German attack of September 1943. However, the cemetery’s most famous residents are the 6/7/11 (depending on your source) miners who died of Spanish Flu in October 1918 and were quickly buried here because of the fear of the infection spreading. The most terrible epidemic to have hit humanity so far, the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918 infected 500 million people around the world and killed somewhere between 50 and 100 million of them. Those who died of the pandemic here in Longyearbyen were buried in permanently frozen terra firma – permafrost – that, it was speculated, may have preserved some of the only active biological samples of a flu strain that whipped out between 3% and 5% of the world’s population exactly a century ago. In a risky bid to better understand the lethal virus that’s still something of a mystery to modern medicine, bodies were exhumed from here in 1998 by a team of international scientists, an undertaking that also ran the risk, however slight, of resurrecting the world’s deadliest flu strain. While ultimately a failure, the scientists thought that if they could find an intact virus locked in the permafrost that they would better understand it, the logic being that by understanding how the virus could change in the future could, quite literally, save millions of lives.

Illegal To Die?

It gets a lot of headlines (Google it), but I’m still not sure how accurate this titbit of Longyearbyen information is, that being that it’s illegal to die here (even if it were true it’s hardly enforceable – doubtless justice would be done, the perpetrator unlikely to be reprimanded). Illegal or no, it’s safe to say that giving up the ghost in Longyearbyen, a settlement displaying an entrenched fear of death and one with very few, if any, elderly residents or facilities to care for the old or frail, is frowned upon. And there’s seemingly a good reason for that, beyond the obvious fact that younger, fitter types would be more suited to living in such a harsh, challenging environment. It all stems from the permafrost, meaning there’s nowhere to bury people, not anymore; natural heaving of the permafrost gradually brings coffins (and bodies) to the surface, not to mention that, and as mentioned above, putting someone in the permanently frozen ground would not only preserve the body, but also any disease that took them down, a big no-no in any modern society, even a small society as this high in the High Arctic. As a result, there are no active graveyards in Longyearbyen, or anywhere on the Svalbard archipelago for that matter. And while the most commonly found cultural monuments on Svalbard are human graves, many of which have been opened and plundered, no one has been buried here for over 8 decades and anyone deemed close to the end must leave for mainland Norway to live out their days, never to return. And if you happen to die here? Well, the town rules say you’ll be flown to the mainland for burial.