Peru

Showcasing One Month Of North-To-South Travels Through Peru, One Of The World’s Richest Heritages Topped By The Legacy Of The Inca Empire

Uros Islands, Lake Titicaca, Peru. August 19, 2015

Peru (July 28 – August 22 2015)

A pictorial recap of north-to-south travels through Peru, one of the world’s richest heritages topped by the legacy of the Inca Empire.

Read all postings from the Peruvian road in chronological order or jump to specific postings using these links.

ARRIVAL – Border Crossing With Ecuador & First Impressions

– THE NORTHERN DESERT – Piura, Chiclayo (Tucume, The Valley of the Pyramids) & Trujillo (Chan Chan & Huacas del Moche)

– THE ANDES – Huaraz, Parque Nacional Huascarán & Yungay

– THE CAPITAL – Lima

– THE SOUTHERN DESERT – Nasca & The Nasca Lines

– CUSCO & THE SACRED VALLEY – Cusco, The Cusco To Machu Picchu Peublo/Aguas Calientes Train, Machu Picchu Peublo/Aguas Calientes, & Machu Picchu

– LAKE TITICACA REGION – Puno, Uros Islands, Taquile Island & Sillustani

DEPARTURE – Bolivia Border Issue

Archived Postings From The Peruvian Road (In Chronological Order)

BORDER CROSSING, FIRST IMPRESSIONS & PIURA

Date || July 28, 2015

Location || Piura, Peru ( )

)

A bridge some two kilometres south of the Ecuadorian town of Macara marks one of three international border crossings with its neighbour Peru. I spent the last few days – via 2 nights in Cuenca & 1 night in Loja, two charming southern Ecuadorian colonial towns that probably deserved more of my time than they got – riding the remainder of the Ecuadorian section of the Pan-American south towards the border. And when I got there shortly after noon today, Peruvian Independence Day no less, I thought I’d reached the end of the line.

Peru as seen across the Macara River outside the town of Macara, southern Ecuador. I’ve no idea what happened to this particular frontier. The operational bridge marking the working crossing between the two countries runs parallel to the bridge that once stood here. I had just been stamped out of Ecuador when I took this picture. A few minutes later I had crossed over, had been welcomed into Peru, & was continuing on my merry way to Piura, my present location & first stop in South American country number 4, some 2 hours & 140 kilometres further south down the Pan-American Highway. At the Ecuador/Peru border crossing outside the town of Macara, southern Ecuador. July 28, 2015.

Peru (The Republic of) || First Impressions

It’s early days of course but even still it’s different. And different is good. It keeps things fresh, reminding me that I’m starting an new adventure within an adventure. Here are a few general observations from today, some of which (9 hours to be precise) I spent on the bus getting here to Piura & the rest of which I spent getting to grips with the city.

• It’s Independence Day

What a day to arrive in the country. Totally coincidental of course but today, July 28th, is Peruvian Independence Day – the country declared independence from nearly 300 years of Spanish colonial rule on this day in 1821.

• Big

Peru is big. Not massive but it’s bigger than Ecuador, that’s for sure.

• A Little Too Canadian

• A Little Too Canadian

The Peruvian flag, which you see everywhere, resembles the Canadian flag, minus that maple-leaf.

• It’s (More) Expensive

Peru is expensive. Well, not really. It’s still quite affordable but it’s more expensive than Ecuador. 19% tax (it was only 12% in Ecuador) added to everything might be the culprit.

• Ceviche & Cuy

One of the many highlights of my almost 4 weeks in Ecuador was ceviche, fresh seafood soaked in lime juice & chillies & served with corn & sweet potatoes. I thought it was an Ecuadorian dish. It’s not. I discovered today that it’s actually a Peruvian dish. Whoops. So is cuy, roasted guinea pig. I wanted to sample that in Ecuador but never got around to it. I’ll get a second chance to do so here.

• Sol

I loved Ecuador, a country rich in oil & with a lucrative tourist industry (it doesn’t seem short of cash). But it annoyed me that they use the US$ as their official currency. Peru has the Sol. That’s not the US$ & that’ll do.

• No Main Terminals Unlike in Ecuador & Colombia, both stupidly easy countries to travel around, there are no main bus terminals/stations here in Peru, just random bus companies with depots here, there & everywhere. That’s not very convenient. It remains to be seen how much of an inconvenience that’ll prove to be.

• It’s Hot & Dusty

The cool climes, greenery & hills of the (Ecuadorian) Andes are gone. For now at least – Peru has Andean peaks that I will, of course, be getting among in due course. But today offered up quite the contrast – I left the winding mountain roads I’d become accustomed to in Ecuador and descended into the desert here in Piura, one of two main cities in the Peruvian northern desert (the other being Chiclayo, my next stop), one of the least touristed parts of the country – touristy Peru is down south.

• Rubbish

There’s rubbish everywhere, Not in the town centres but on the outskirts and along the roads. It’s a real problem, a real eyesore. I didn’t see that in Ecuador even though they have outskirts & roads there too. • Taxi Just like in Ecuador, little yellow ‘official’ taxis swarm everywhere but seemingly every car plying the roads in Peru is a taxi. All cars beep to signal their approach & to advertise their availability. It’s bizarre. And noisy.

• Tuk-Tuks

Moto & peddle powered tuk-tuks are everywhere. I didn’t see one during almost 4 weeks in Ecuador.

Piura

Piura is a nice introduction to the country. It’s historical clout aside (Piura was the first Spanish settlement in Peru after they ousted the Incas back in 1532), there’s not a whole lot to see here per se but as a passing through stop over to destinations that do offer attractions then Piura could do worse. In places it’s rather pretty.

Piura is a pleasant, laid-back place with a gorgeous central plaza, Plaza de Armas, overlooked by the requisite cathedral. This isn’t Plaza de Armas. This is Plaza Pizarro. More an elongated square than a true plaza, it’s a a shady spot with fountains, a statue or two & more than a few Peruvian flags, I guess for the day that’s in it. It’s rather picturesque, or at least it was this afternoon bathed in soft late afternoon light. Plaza Pizarro, Piura, northern Peru. July 28, 2015

Moving On

Tomorrow I’ll continue south down the Pan-American through the ‘formidable’, according to RoughGuides, Sechura Desert that hugs the Pacific Ocean coast south of here, reaching all the way inland to the foothills of the Andes Mountains. I’m headed for the city of Chiclayo where I plan on staying put for a few days while checking out some pre-Inca ruins in the process. Staying put for a few days. That’ll be nice.

PERUVIAN NORTHWESTERN DESERT - CHICLAYO & TUCUME (THE VALLEY OF THE PYRAMIDS)

Date || July 29, 2015

Location || Chiclayo, Peru ( )

)

Sechura Desert Desolation

I made it all the way down the mundane, 210 kilometre-long stretch of Pan-American Highway connecting the northern Peruvian cities of Piura & Chiclayo. However, the bus I started the 4-hour journey on wasn’t as fortunate.

A half hour out of Piura and we pulled over. Nothing to see here I thought, just more sandy Sechura Desert desolation. We were still there 20 minutes later. People started getting off, wondering what was going on. Then everyone got off & unloaded their luggage when it became apparent that the bus was sick, that it wasn’t going anywhere, & that another bus, a rescue bus if you will, had arrived behind us. It got somewhat heated when it was discovered shortly thereafter the rescue bus was full – ‘No asientos’ (‘no seats’) was the cry. Transferred luggage was unloaded again, the rescue bus pulled off and we stood there by the side of the Pan-American Highway waiting. I was totally oblivious to what was happening, which wasn’t a whole lot, until eventually another bus rode up, this one with sufficient space, and we were off. We made it the rest of the way to down the 1N, the Peruvian portion of the wider Pan-American Highway, to Chiclayo without any more dramas. Breakdown on the of N1/Pan-American Highway en route from Piura to Chiclayo, northern Peru. July 29, 2015.

It’s still novel to be viewing this kind of flat, unending, forlorn landscape having recently descended from the Ecuadorian Andes. It’s so uninviting that I actually found myself noticing & playing with the mark on the inside of the window of the bus. Anything to pass the time. A portion of the Peruvian Sechura Desert, which from here runs all the way to the Pacific Ocean, some 20 kilometres in the distance, as seen from a Transportes Chiclayo, Brazilian-manufactured Marcopolo bus riding the 1N, the Peruvian Pan-American Highway, en route from Piura to Chiclayo, northern Peru. July 29, 2015.

Chiclayo

Chiclayo is the commercial centre of northern Peru & the largest settlement in the Peruvian northern desert. It’s a busy place, one I assume doesn’t get too many tourists if the attention I garnered today on the streets is any indication. There’s not a lot to see in the city itself (the leafy central plaza, complete with benches, water features, & ice-cream vendors & ringed by attractive colonial-era buildings, including the prominent, ever-present cathedral, is a Latin American standard) with the real regional highlights being the ruins of pre-Inca ceremonial centres not far from the city. That’s what’ll keep me busy tomorrow but on today’s amble around Chiclayo I stumbled across the city’s Central Market, supposedly one of Peru’s best.

Chiclayo’s Central Market, a.k.a. Mercado Modelo, sells a lot of stuff over a rather large area of covered lanes filled with stalls, many of which spill out onto the surrounding streets – the usual hectic, developing nation market scene. But as with any market it mostly sells food, some of it not even dead. I tried to drum up conversation with this turkey but he was having none of it. Resigned to his fate, he chose instead to wallow in self-pity, as was his want. Central Market/Mercado Modelo, Chiclayo, northern Peru. July 29, 2015.

Tucume || The Valley of the Pyramids

The first of three sets of dusty ruins I snooped around in this northern region of the country was at Tucume, a.k.a. the Valley of the Pyramids. Located about 35 kilometres north of Chiclayo, this site is a product of the Sican culture (800 – 1375 AD). It came into being in approximately 1100 AD when the elite of Sican society controlled a complex administrative system, including developing an extraordinary irrigation solution which channelled water from the region’s Chancay River, to build a city of 26 truncated abode block pyramids, only the largest complex of monumental adobe structures in the New World. Built around the base of the sacred Cerro Purgatorio mountain, a religious centre believed to connect the heavenly world, our world, with the world of the dead, the 500-acre site also housed metallurgical workshops & cemeteries. Although subsequently inhabited by the Chimu (750 – 1470 AD) & Inca (1470 – 1532 AD) cultures following the demise of the Sican, the site remained the most important centre of political & religious power in the region until its abandonment following the early 1530’s conquest of the Inca Empire by the Spanish. Having been built entirely from mud bricks, Tucume’s structures didn’t weather well with the passing of time & it wasn’t until the late 1930’s that first scientific excavations took place, work still ongoing today.

My visit to the Tucume archaeological complex was a bit of a damp squib. The site’s main pyramid & seat of political power during Tucume’s peak of the 13th & early 14th centuries, the Long Pyramid, was off-limits. I did take a look around the so-called Storehouse, an excavated area at the southeastern side of the 30-metre-high Huaca 1 (Pyramid 1), seen here in the distance – yes, that’s a pyramid, a big, multi-level, 900-year-old pile of adobe mud bricks. One of the larger pyramids in Tucume, & one that was also in use during the Chimu & Inca period, Huaca 1 it was the seat of local political power and served as the residence of lords & their elite servants – all Tucume pyramids served as residences for members of the highest social rank of Sican society. It is speculated that the Storehouse, safe from the elements under the swath of corrugated iron seen here at the base of Huaca 1, once held luxury goods – ritual seeds, finely woven cloths etc. – for use by the Tucume’s nobility. Today it’s a live archaeological dig site, much like the rest of the Tucume site. This picture was captured from the lookout high on 197-meter-high Cerro Purgatorio mountain around which all the site’s structures are located. Once deemed a deity to which only Tucume priests had access to, today the mountain is still deemed sacred. But don’t worry. Once you pay the site’s entrance fee of Sol 10 (€2.90) you’re free to access it. Whether you’ll be cursed as a result remains to be seen. Tucume Archaeological Complex outside the modern-day village of Tucume, northwestern Peru. July 30, 2015.

Abobe, sun-dried mud bricks, on the floor of the Storeroom of Huaca 1 (Pyramid 1). Millions of such bricks were used to construct not only the structures here at Tucume but at all the pre-Inca ruins I’ve visited these past few days in this desolate region of Peru. I get it. Lack of alternatives – forests were scarce, quarries even scarcer – left the builders with very few material choices. Frankly, and even allowing for the severely weathered present-day state of some of the structures I’ve seen this week, I’m impressed they have lasted as long as they have given the delicate nature of mud/muck bricks. As seen here, each brick carried the distinctive mark/brand of its manufacturer/provider, clear evidence that everyone in society mucked in, if you’ll pardon the pun, when it came to sourcing the materials needed to build societal structures. Huaca 1 (Pyramid 1) of the Tucume Archaeological Complex outside the modern-day village of Tucume, northwestern Peru. July 30, 2015.

PERUVIAN NORTHWESTERN DESERT - TRUJILLO, CHAN CHAN & HUACAS DEL MOCHE

Date || August 2, 2015

Location || Trujillo, Peru ( )

)

Located between the Andes to the east and Pacific Ocean to the west, this narrow coastal region of northwestern Peru is desert. Pure, sand everywhere desert. Needless to say it’s not a very inviting place, naturally irrigated only in patches by rivers that run down from the mountains. I’ve spent almost a week here now creeping down the coast and exploring some of the various dusty ruins that dot the region, ruins of advanced, pre-Inca societies – namely the Moche (0 – 750 AD), Sican (800 – 1375 AD), & Chimu (750 – 1470 AD) civilizations – that, and although having the ability as long ago as 1800 years to weld, work precious metals, & ingeniously divert water sources for irrigation, still chose to set up shop here in this arid part of the continent. They must have seen something in the landscape that I haven’t over the last week. All I’ve seen is sun, (far off) sea & sand, (not that kind of sun, sea & sand) & extremely weathered centuries-old structures made of adobe bricks. Lots of extremely weathered centuries-old structures made of lots and lots and lots of adobe bricks.

A guide at the Chan Chan Archaeological Zone on the outskirts of Trujillo, northwestern Peru. August 1, 2015.

Trujillo

I moved 4 hours south down the Pan-American Highway from Chiclayo to the town of Trujillo, Peru’s northern capital & the country’s third city (after Lima & Cusco), a Spanish settlement founded in 1534 by Pizarro, the Spanish conquistador who conquered the Incas in 1532. Pre-arrival the city for me was nothing more than an afterthought – I was coming here merely to use it as a base for visiting two more adobe brick-heavy, desert archaeological sites surrounding the city, Chan Chan & Huacas del Moche. Maybe it was the glorious sunny weather I was greeted to upon arrival. Or maybe I was just missing some gorgeous, colourful, colonial-era architecture (it has been a while). Maybe it was both but whatever it was Trujillo postponed my plans to run straight for the desert sands upon arrival on my first afternoon in the city. Instead I found myself spending the afternoon wandering around & photographing what has been my favourite city in Peru thus far.

The Municipalidad building on Plaza Major in central Trujillo, northwestern Peru. July 31, 2015.

Even though I had read that lively, cosmopolitan Trujillo was renowned for its lavish colonial architecture & colourful old mansions, some 20 blocks of it all told, I still got a pleasant surprise when I laid eyes on the gorgeous buildings enclosing the city’s gorgeous & expansive Plaza Mayor, not to mention the whitewashed buildings lining its Spanish-style main pedestrian street, Jiron Pizarro. At times looking around I felt like I was in Andalusia. Trujillo. A Peruvian desert oasis indeed.

Trujillo’s Plaza Mayor is full of benches, palm trees & shiny marble. It is surrounded by colourful mansions & civic building & overlooked by the city’s mid-eighteenth century cathedral, La Catedral, seen in the distance. All told it is one of the most attractive central plazas I’ve yet visited in any Latin American city. Plaza Mayor, Trujillo, northwestern Peru. July 31, 2015.

Malaga? No, it’s Jiron Pizarro, central Trujillo’s main/only pedestrianised street, one that’s lined with bright colonial buildings all of which sport a minimum of one red & white Peruvian flag. Jiron Pizarro, Trujillo, northwestern Peru. July 31, 2015.

As if Plaza Mayor wasn’t photogenic enough. I’m not too sure what was going on here but an early evening group run of some hundreds, who were running & chanting in unison around the perimeter of Plaza Mayor, meant this was both an audio & visual treat to cap my first evening in the city. In the background is a section of the facade of the plaza’s La Catedral. Plaza Mayor, Trujillo, northern Peru. July 31, 2015.

Chan Chan

The ancient archaeological sites dotted around the Moche valley outside the city of Trujillo – pyramids, courtyards, high walls and temples, again all constructed from adobe, sun-dried bricks – were the reason I came to the city of Trujillo. The reason most people who bother to stop here do so (and not many do). And once I got the colonial architectural gems of the city itself out of the way I was ready to return to the dust of the desert to see the remnants of the ancient cultures that once thought it a good idea to call these lands home. First up, UNESCO-listed Chan Chan, capital of the Chimu civilization.

A statue & adobe carving detail on the walls of Plaza Principal of the Chan Chan Archaeological Zone on the outskirts of Trujillo, northwestern Peru. August 1, 2015.

Chan Chan & The Chimu Chan Chan, located on the northern edge of present-day Trujillo, is a ruined adobe city built by the sea in the 13th century by the Chimu culture (750 – 1400 AD) as the capital of their Chimu Empire. The largest pre-Columbian city in the Americas, it’s a huge complex only a small walled portion of which, the so-called Tschudi temple-citadel, has been excavated for display to the public; the majority of the site has suffered badly from a combination of the passing of time & the occasional rains over the last 800 years or so. Very different in appearance from the large pyramid sites of Tucume or Huacas del Moche (next), Chan Chan is a low-lying (no more than 16 metres above sea level), spread-out complex of brightly painted & tapered adobe brick walls, plazas, flat-topped buildings, & temples, the latter of which were panelled with gold & precious metals – the Chimu were expert goldsmiths. The city went into decline, as did the Chimu civilization itself, in the 1470’s when the Inca armies cut off aqueducts supplying Chan Chan the water vital to its survival. Sixty years later, with the arrival of the Spanish, the city was nothing but a ghost town full of dust & legend, something the majority of the UNESCO World Heritage-listed site still resembles today.

The Plaza Principal of the Chan Chan Tschudi temple-citadel is the site’s main plaza, an expansive space surrounded by low-lying adobe walls adorned with astonishing motif carving, a feature of the site. This space was considered sacred and was used for ceremonial celebrations attended only by the priests & upper echelons of Chimu society. From here the rest of the citadel, a maze of abode-walled corridors, chambers, & smaller plazas, can be explored but a little imagine is required to get an appreciation for the way the place must have looked way back when. Plaza Principal of the Chan Chan Archaeological Zone on the outskirts of Trujillo, northwestern Peru. August 1, 2015.

– UNESCO commenting on the Chan Chan Archaeological Zone

Probably one of the most beautiful & certainly one of the world’s largest pieces of public art (it’s hundreds of metres long), the mosaic on the external street-facing walls of the Universidad Nacional de Trujillo chronicles both Peru’s landscape and history in amazing detail right from the earliest cultural manifestations & pre-Inca cultures (Moche, Sican, Chimu etc.) right through to the Inca & Spanish conquest & ultimately the founding of the Republic in 1821. I passed this having returned to the city after visiting the Chan Chan archaeological site, 5 kilometres north of the city, & while en route to the Huacas del Moche archaeological site, 7 kilometes south of the city. Needless to it’s a sight that detained me for a while. Trujillo, northern Peru. August 1, 2015.

Huacas del Moche || Huaca de la Luna & Huaca del Sol

The last ancient archaeological site I visited over the last few days really was ancient, and really was impressive. Situated some 7 kilometes south of present-day Trujillo in a barren desert valley beside the Rio Moche is what remains of the capital of the Moche civilization (0 – 750 AD), one that left behind not one but two massive abode brick structures, the closed-to-the-public Huaca del Sol (Temple of the Sun), the largest adobe structure in the Americas, & Huaca de la Luna (Temple of the Moon), very much open for perusal. And if you can’t satisfy your inner Indiana Jones cravings when snooping around these ancient piles of adobe bricks then you never will.

The Huaca de la Luna (Temple of the Moon), although smaller than the neighbouring Huaca del Sol (Temple of the Sun), is the scene of intense excavations, and has been for almost 2 decades now – a picture on display taken in 1998 shows the whole site as one big, big, big pile of rubble. Nestled at the base of the mountain Cerro Blanco, which the Moche deemed sacred, the multi-level structure, which can only be accessed via a guided tour, is a hulking maze of adobe brick walkways, plazas, tombs, & interconnected patios. It was built in many stages – old constructions were filled in with adobe bricks and reconstructions were built on top, creating the multi-level structure seen today – over a 700 year period, effectively mirroring the period of the Moche civilization itself. The main form of the present-day Huaca de la Luna (Temple of the Moon) comprises two main temples – the so-called Old Temple, built & used between 100 & 600 AD, & the so-called New Temple, built and used between 600 and 800 AD. They combined to from the Moche’s axis mundi, the centre of their world, where the earth was symbolically joined with the upper world of the gods and the lower world inhabited by their ancestors, who were buried at the foot of and in the interior of this sacred building. It was at the Huaca de la Luna (Temple of the Moon) that the most important rites associated with the Moche religion were performed. This included the Sacrifice Ceremony, when a defeated combatant would be offered up to appease the gods in a bid to re-establish and ensure both political & cosmic order. This ceremony occurred with greater frequency at times of trouble, such as the climatic variations caused by the El Nino phenomenon or after a powerful earthquake, when it was believed that offerings in the form of human blood, were needed to calm the anger of the gods. Huaca de la Luna (Temple of the Moon) at the base of Cerro Blanca, Moche, northwestern Peru. August 1, 2015.

The highlight of a snoop around the innards of the Huaca de la Luna (Temple of the Moon) is the amazing painted friezes & murals that adorn some of its walls. Easily the temple’s most striking feature, to date over 6000 square metres of polychrome reliefs & murals have been uncovered & restored, an unbelievable accomplishment given the scale of the task that faced the restoration team when first starting on task in 1998. This is a picture of the artistic highlight of the Huaca de la Luna (Temple of the Moon), the amazing murals adorning the 7-tier north face of the Old Temple as seen from the temple’s Great Plaza, only 4 tiers of which are shown here (from bottom to top: Procession of victorious & vanquished warriors, Priests holding hands as if dancing, two spiders with a shared abdomen, The Fisher god). Adobe murals on the 7-tier north face of the Old Temple of Huaca de la Luna (Temple of the Moon), Moche, northwestern Peru. August 1, 2015.

Five-hundred metres across the desert plain from the Huaca de la Luna (Temple of the Moon) is the largest mud-brick pyramid in the Americas, the Huaca del Sol (Temple of the Sun). The massive structure, used as a residence for the Moche rulers & constructed at the same time as the Huaca de la Sol (Temple of the Moon), is thought to have been constructed using some 140 million adobe bricks. It’s quite the sight, it’s hulking mass probably accounting for why the smaller Huaca de la Luna (Temple of the Moon) gets all the archaeologists love – where to even start excavating this beast? As big as it is, the present structure is estimated to be only some 30% the size of the original construction. The Spanish diverted a nearby river in 1602 in a futile attempt to access internal treasures. All they succeeded in doing was washing away the bulk of the then 1100-year-old structure. For their efforts they were presented with adobe bricks. No treasure. Just adobe bricks. Lots of them. Huaca del Sol (Temple of the Sun), Moche, northwestern Peru. August 1, 2015.

Moving On || Mountain Bound

I’m done with the Peruvian desert & I’m heading for the hills again. Huaraz, high in the Peruvian Andes, to be precise. At over 3000 metres above sea level, the valley city is billed as one of the best places to experience the Peruvian Andes. Sounds good to me. I planned/wanted to go there today, Sunday, but I have wait another day for a bus ticket – Peru doesn’t do bus travel like Ecuador, or even Colombia for that matter. So I’ve one more day in Trujillo. I could think of worse places to kill a day, even if that day is a Sunday – it’s as sleepy & slow a day here as it is in other regions of Latin America, somewhere that really keeps Holy the Sabbath. Some say when you travel every day is a holiday & every night a Saturday night. Except when it’s a Sunday in Latin America that is.

PARQUE NACIONAL HUASCARAN, HUARAZ & YUNGAY

Date || August 5, 2015

Location || Huaraz, Peru ( )

)

The bus driver taking me up the Santa Valley from Huaraz to Yungay earlier today was surely aiming for some kind of land speed record, his lead-footed exploits curtailed only by the ubiquitous speed bumps found on Peruvian roads. I was conscious of his recklessness but at the same time preoccupied with the stunning scenery all around me with the snow-capped Cordillera Blanca range to my right & the snowless Cordillera Negra range to my left. If I was going to die today, I thought, then I’d already be half way to heaven. And about an hour later – and after enduring a second memorable journey on this day, a bumpy, dusty, & windy shared taxi ride from Yungay high up into the Cordillera Blanca range to the shores of Lago (Lake) Chinan Cocha in Parque Nacional Huascarán – I felt like I had actually arrived (in heaven that is).

Lago (Lake) Chinan Cocha in UNESCO-listed Parque Nacional Huascarán, Ancash, Peru. August 5, 2015.

Parque Nacional Huascarán || Las Lagunas de Llanganuco & Huascarán

UNESCO-listed Parque Nacional Huascarán (Huascarán National Park) is located high in the Cordillera Blanca range of the Peruvian Andes, the highest tropical mountain range on earth, a 160-kilometre-long chain of 35 summits, many of which are over 6000 metres and the highest of which is the 6,768-metre-high Mount Huascarán, Peru’s highest peak. The park’s undoubted highlight is the dual Lagunas de Llanganuco (Llanganuco Lakes) of Lago (Lake) Chinan Cocha & Lago Orcon Cocha, two stunning deep-blue lakes surrounded by towering walls of rock & snow-capped peaks of the Cordillera Blanca range.

A boatman on Lago (Lake) Chinan Cocha in Parque Nacional Huascarán, Ancash, Peru. August 5, 2015.

– UNESCO commenting on Huascarán National Park

Lago Chinan Cocha sits at an altitude of 3,850 metres meaning the air up here is chilly & thin enough to remind you that you’re almost 4 kilometres above sea level. There’s not whole lot to do once you get here – the lake marks the end of the road up into the Cordillera Blanca from the Santa Valley town of Yungay – but just taking in my surroundings was activity enough for me to pass the time I spent here. However, some of the Peruvians in attendance felt the need to take a brief trip out on the choppy waters of the lake. Each to their own.

Boating on Lago (Lake) Chinan Cocha in Parque Nacional Huascarán, Ancash, Peru. August 5, 2015.

Others were happy to stay on terra firma and get a few shots for the family album.

Pictures by Lago (Lake) Chinan Cocha in Parque Nacional Huascarán, Ancash, Peru. August 5, 2015.

After my lakeside high jinks, it was back to the Santa Valley town of Yungay, the sobering scene of Peru’s worst natural disaster.

Yungay || Old & New

The Santa Valley town of Yungay is just one of many towns that lie under the western shadow of the Cordillera Blanca range, some 25 bumpy, dusty & windy kilometres from the Lagunas de Llanganuco (Llanganuco Lakes). There used to be only one Yungay but since May 31, 1970 there has been two.

One of the many memorial crosses at the site of the submerged old town of Yungay, Ancash, Peru. August 5, 2015.

Ancash Earthquake & Landslide & The Old Town of Yungay

On May 31, 1970, a massive earthquake, the Ancash Earthquake, also known as the Great Peruvian earthquake, dislodged the northern wall of Mount Huascarán causing a landslide of some 80 million cubic metres of water, mud & rock that travelled at over 300 kilometres per hour down the valley, completely submerging the town of Yungay. Estimates put the death toll in the town at over 70,000 – the majority of the town & its inhabitants simply disappeared within seconds. It still remains to this day Peru’s worst natural disaster, not to mention the world’s deadliest avalanche. Today the old town of Yungay, 2 kilometres up the Santa Valley from the new settlement, is a memorial to the event, a vast space of hardened mud & moraine covering what was once Yungay – remnants of the town’s once proud cathedral, palm trees that once adorned its central plaza, and a twisted, rusted bus all break the surface as eerie reminders of the past.

A very right-of-centre obelisk, erected in 1995 & commemorating the Ancash Earthquake & subsequent landslide, in the old town of Yungay. The site, one big graveyard crisscrossed by paths & dotted with crosses, has been beautified thanks to a donation by the Japanese government of thousands of rose bushes. In the background, only some 15 kilometres as the crow flies, is the north wall of Mount Huascarán, the culprit. The highest point of all the Earth’s Tropics, the fourth highest mountain in the Western Hemisphere and Peru’s highest peak, it has two distinct summits – the 6,768-metre-high south summit (left) & the 6,654-metre-high northern summit (right). The old town of Yungay, Ancash, Peru. August 5, 2015.

Locals on the streets of the new Yungay, situated 2 kilometres from old Yungay in a safer, more sheltered section of the Santa Valley, or so everyone hopes. Yungay, Ancash, Peru. August 5, 2015.

HUARAZ

Huaraz

I’ve based myself for the last 3 days in Huaraz, the capital of the Ancash region of Peru & the largest town around. I didn’t do a whole lot in Huaraz. There isn’t a whole lot to do. Most travellers who find themselves here use the city as a base for forays into the surrounding hills – the place is awash with travel & tour agents all offering the same high-altitude thrills.

Huaraz is a market town that bustles most hours of the day. Aesthetically it doesn’t have a whole lot going for it – it’s a city of streets & avenues in grid form – but I’m not going to rip on it too much; 80% the town was razed during the 1970 Ancash Earthquake and seemingly it has been somewhat haphazardly patched up ever since. On the streets of Huaraz, Ancash, Peru. August 4, 2015.

The Descent

I’m heading for the capital, Lima, in the morning. Back down to sea level. Aside from it being typically busy, I’ve really no idea what to expect from the Peruvian capital; I haven’t yet read up on it. But with an 8-9 hour bus ride to look forward to tomorrow I guess I’ll have ample time to tend to that detail.

LIMA

Date || August 9, 2015

Location || Ica, Peru ( )

)

I wouldn’t exactly class the Peruvian capital of Lima as a must-see. It does some Peruvian stalwarts pretty well, maybe even better than anywhere else in the country, namely colonial architecture, museums, food & nightlife. But it also tops the Peruvian league when it comes to noise, traffic (oh the traffic), expense & general frustrations – dealing with the legions of different bus companies that are located in various parts of the city, none of which are convenient to get to/from, when trying to organise leaving the city will be my enduring memory of the three nights I spent in Peru’s largest urban centre before escaping it for my present location of Ica, some 4 hours down the dusty, desert coast via the Pan-American Highway.

Lima’s Catedral as seen from across Plaza Mayor in Lima Centro, Lima, Peru. August 7, 2015.

The Peruvian capital is a huge metropolis of long, straight avenues & home to a boisterous & fascinating mix of some 9 million. There has been a city here, sitting on the Peruvian Pacific coast equidistant from the Ecuadorian border to the north & Chilean boarder to the south, stretching back well before pre-colonial days but Spanish Lima, nicknamed the “City of Kings”, was founded in 1535 by Francisco Pizarro, 3 years after he lead the band of conquistadors that brought an end to the Inca Empire. A pioneering city from the get-go (the continent’s first university, the University of San Marcos, was founded in the city in 1551), the city went on to become the capital of the Spanish interests in South America – present-day Peru Ecuador, Chile & Bolivia. Considered South America’s most beautiful city during the 16th & 17th centuries, something you’d scarcely believe today, it suffered over the years & as been especially blighted by earthquakes. But it has also continued to expand, remaining the most important & richest city in South America right up until the 19th century. Today it’s a bustling city with a large percentage of the population inhabiting the outlying shantytowns, lured down from the Andes or in from the countryside with the hopes of eking out a better, more prosperous existence.

In a city of numerous, spread-out suburbs, it’s the historic city centre, Lima Centro, the city’s UNESCO-listed old colonial heart & its architectural & cultural hub, that draws most visitors. A typically Spanish-era district of narrow streets lined by mansions with overhanging balconies and churches at every turn, it is dominated by two large plazas, Plaza San Martin & Plaza Mayor. This is a picture captured on Jiron Ucayali in Lima Centro, a pedestrianised street between the two main plazas and one of the best places in the city to view Lima’s elegant, dark-wooded overhanging balconies that give a somewhat distinctive architectural flavour to this particular Spanish settlement. Architecture & pedestrians on Jiron Ucayali in Lima Centro, Lima, Peru. August 7, 2015.

– UNESCO commenting on the Historic Centre of Lima

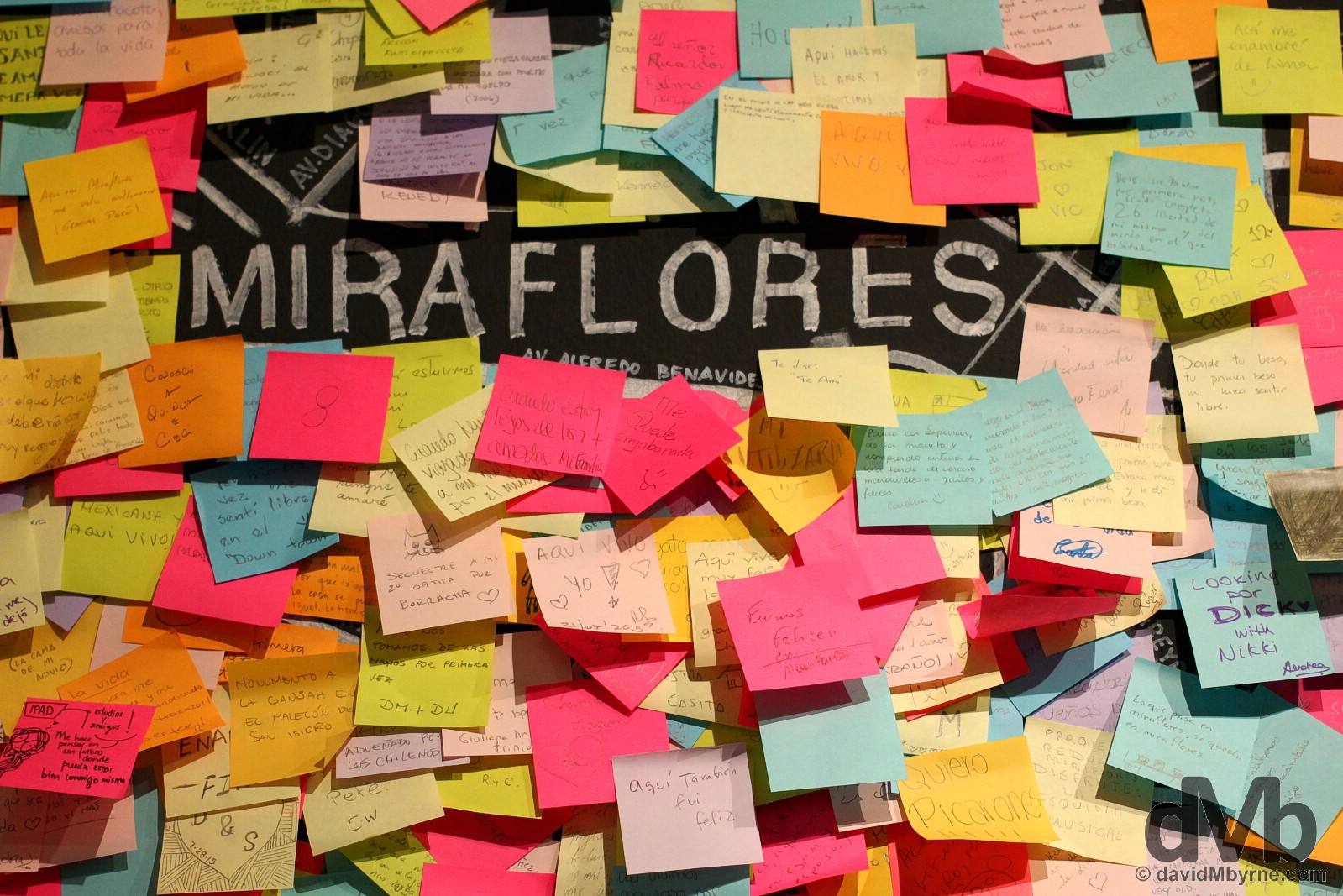

Miraflores

Some 7 kilometres from Lima Centro is Miraflores, the modern commercial heart of the city & the suburb of the city I called home. A favourite foreigner hangout & the address to which many of Lima’s businesses have relocated to in recent years, it’s a district of trendy cafés, restaurants & bars, meaning there’s a definite air of prosperity here compared to other areas of the city.

Post-it notes in an exhibition, entitled ‘Capital Intervencion’, in the Centro Cultural de la Municipalidad de Miaflores. I went here to view a photography display that wasn’t happening but the sea of Post-it notes covering a massive wall-mounted map of Lima was a nice colourful consolation. The Centro Cultural de la Municipalidad de Miaflores, Miraflores, Lima, Peru. August 8, 2015.

Rather bizarrely, right in the centre of urban Miraflores is Huaca Pucllana, a pre-Columbian temple & tomb, a vast mound of millions of adobe bricks that has survived to this day where others haven’t – this whole region was once dotted with such structures prior to the arrival of the Incas & then the Spanish. This was a particularly grey day in the Peruvian capital. Seemingly the sun is a visitor to these parts only for brief periods during the South American summer (December to March). Most of the rest of the year the city is typically blanketed by a low mist, a solid grey blanket. That’s how every day was for me in Lima. Huaca Pucllana, Miraflores, Lima, Peru. August 8, 2015.

NASCA & THE NASCA LINES

Date || August 11, 2015

Location || Nasca, Peru ( )

)

It wasn’t long after leaving Lima that the sun reappeared. And the sand/dust too. Four hours down the Pan-American coast is Ica, a dusty settlement that was home for a night, but only because of a failure to get a direct bus from Lima to Nasca, my present location a further 3 hours south of Ica. Nasca is a dusty place too – the whole Peruvian Pacific coast is, from way up north to way down south – but at least the desert around here has something worth stopping off for, namely the UNESCO-listed Nasca Lines, a series of ancient designs in the desert plains surrounding Nasca that just happen to be one of the great unsolved mysteries of the South American continent.

The so-called Monkey of the Nasca Lines as seen from upon high. One of the better known zoomorphic Nasca Line shapes, the distinctive spiral tail of this 55 metre-long design is used as icon for the national tourism board of Peru. Pampa de San Jose/Nasca plain, southern Peru. August 11, 2015.

The Nasca Lines || How & Why?

The Nasca Lines are a group of gigantic zoomorphic, anthropomorphic & geometrical designs on the surface of the vast desert plain outside the town of Nasca. Created by the ancient Nasca culture over an estimated 1000 year period – sometime between 500 BC & 500 AD – the designs, a combination of straight lines & stylized drawings some of which are 300 metres long, are mostly rock patterns although some were created by simply clearing the desert surface of sand & stone to the required design. Covering an area of some 450 km² of the Pampa de San Jose, a.k.a. the Nasca Plain, no one really knows how the designs were made (they can’t be viewed from ground level so crafting them must have been quite the undertaking) or why.

I took a Cessna ride in the skies above the Nasca plain to get a bird’s-eye view of the Nasca Lines, the only vantage point from which to truly appreciate them. This is a picture of the Cessna C206 I was a passenger of sitting on the tarmac of Nasca Airport prior to departure. Nasca, southern Peru. August 11, 2015.

The Nasca Lines || Discovery & Meaning

Only ‘discovered’ in 1927, first viewed from the air in 1930s, & declared a World Heritage site by UNESCO in 1994, theories abound as to the meaning & purpose of the Nasca Lines, so much so that today they remain one of the great mysteries of South America. Everything from landing pads for aliens to ritual pathways to a system mapping the existence of aquifers has been put forward. However, the most widely believed theory says the designs were an astronomical calendar linked to the rising & setting points of celestial bodies on the east & west horizons, a theory put forth by Maria Reiche, a German who studied the lines almost continuously from 1946 until her death in 1998. Uncertainty over their origin & purpose there may be, but their present-day function couldn’t be better understood, that being to extract a lot of money from a lot of tourists – flights over the lines, weather permitting & starting at about US$100 for a 25 minute jaunt, aren’t exactly cheap.

The weather & thus viewing conditions were great but the compact 4-seater (6 seats if you include the pilot & co-pilot… I do, they are important) Cessna C206 still bounced around quite a bit. It took all the concentration I could muster to avoid spewing a few times during the 25-minute flight. That coupled with the cramped conditions meant photography was quite the challenge. Pilot, left, & co-pilot, who ably doubled as scenic commentator, in the compact cockpit of a Cessna C206 over the Nasca Plain in southern Peru. August 11, 2015.

Needless to say, from my vantage point I saw a lot of emblematic structures far below. Somewhat ironically I flew over the Condor, the Humming Bird, the Parrot, & the 300 metre-long Heron. I also saw the trapezoids, the Monkey, the Dog, & the Whale. They were all pretty cool but my favourite of the lot was this, the 32 metre-high Astronaut. Also called the ‘owl man’ or ‘bird man’ by some, this is probably the most controversial of all Nazca figures/designs, his combination of unusually round head, goggle-shaped eyes, & boots and index finger pointing to the sky has millions convinced that it is a depiction of an Alien Astronaut. However, others, mostly conventional archaeologists, are convinced that it is in fact a fisherman; they claim that he is holding a fishing net in one hand. Whatever the symbolism represents, I’m just glad I got to see it with my own eyes (& even happier still to photograph it). The Astronaut of the Nasca Lines, Nasca Plain, southern Peru. August 11, 2015.

– UNESCO commenting on the Lines and Geoglyphs of Nasca and Pampas de Jumana

You don’t have to take to the air to see the lines. You should, but don’t have to. This is a picture captured from the Cessna of the ground level viewing tower (top-right of the image) situated by the Pan-American Highway some 20 kilometres from Nasca town. There are a few Nasca designs in the desert sands just beyond the tower, as seen here, but from such a low vantage point one can’t really get much of an appreciation for the lines. Needless to say viewing the Nasca Lines from the air is the only real way to fully appreciate their zaniness. The Nasca Plain, southern Peru. August 11, 2015.

Cusco Bound

And that’s it from the Peruvian desert. I’m heading inland tonight on the overnight bus to Cusco. Back once again to the hills, back once again to the Andes. Cusco, a city that has been on my bucket list forever, needs little introduction – as the former capital of the Inca empire & the gateway to their lost Andean fortress of Machu Picchu, it’s both one of South America’s most historic & most visited cities. Not long to wait now.

Cusco Bound

And that’s it from the Peruvian desert. I’m heading inland tonight on the overnight bus to Cusco. Back once again to the hills, back once again to the Andes. Cusco, a city that has been on my bucket list forever, needs little introduction – as the former capital of the Inca empire & the gateway to their lost Andean fortress of Machu Picchu, it’s both one of South America’s most historic & most visited cities. Not long to wait now.

CUSCO & THE SACRED VALLEY

Date || August 13, 2015

Location || Cusco, Peru ( )

)

I had a good look around Cusco today, my first full day in probably the continent’s biggest draw as a traveller’s & tourist mecca. More to come of course from this city, the former capital of the Inca empire, but tomorrow I’ll be heading for the nearby so-called Sacred Valley, the end of which is the Inca’s famed Andean fortress of Machu Picchu. I’ll be back in Cusco before too long but for now here’s a few pictures from today captured in two of the city’s many plazas.

Plaza de Armas, Cusco, Peru. August 13, 2015.

Plaza Regocijo, Cusco, Peru. August 13, 2015.

More pictures from my time in Cusco, pre- & post-Machu Picchu.

- Calle Hatunrumiyoc in Cusco, Peru. August 13, 2015.

- Plaza Regocijo, Cusco, Peru. August 13, 2015.

- Do Not Sit On The Inca Wall. A sign in the Qorikancha Complex in Cusco, Peru. August 13, 2015.

- Seated during festival festivities in Plaza de Armas, Cusco, Peru. August 16, 2016.

- Iglesia de La Compania overlooking Plaza de Armas in Cusco, Peru. August 17, 2016.

- La Catedral overlooking Plaza de Armas during festivities in Cusco, Peru. August 16, 2016.

- The Central Courtyard of the Qorikancha Complex in Cusco, Peru. August 13, 2015.

- A military procession as part of festival festivities in Plaza de Armas, Cusco, Peru. August 16, 2016.

- Plaza Regocijo, Cusco, Peru. August 13, 2015.

- Plaza de Armas, Cusco, Peru. August 16, 2016.

- Traditional Andean Cuy, deep-fried guinea pig, an a restaurant in Cusco, Peru. August 17, 2015.

THE CUSCO TO MACHU PICCHU PEUBLO/AGUAS CALIENTES TRAIN

Date || August 14, 2015

Location || Machu Picchu Pueblo/Aguas Calientes, Peru ( )

)

You’ve basically two options when it comes to getting yourself from the old Inca capital of Cusco to Machu Picchu, the lost & then rediscovered Inca citadel high in the Peruvian Andes, Peru’s shining jewel & probably the most famous & most visited tourist destination on the whole South American continent. With no roads serving the section of the so-called Sacred Valley where the Incas chose to build their mountaintop fortress, you can either walk there via the fabled Inca Trail… or you can take the train. For the former you’ll be required to put your name on a 6 month+ waiting list, pay upwards of $1000, & then walk for up to a week. The latter sees you riding a train for 3 hours from Poroy, a 12 kilometre taxi ride outside of Cusco, to Machu Picchu Peublo/Aguas Calientes, which in turn is connected to the gates of Machu Picchu itself by road via a windy, 25-minute bus ride (or stiff 90-120 minute hike). Now, I’m all for trekking & once-in-a-lifetime experiences but not wanting to fully succumb to Machu Picchu’s over-commercialisation saw me picking the lesser of two evils for accessing the site, somewhere that, & while obviously a victim of its own success, is still somewhere that transcends the hype, somewhere that cannot & should not be missed when embarking on any trip to this part of the world.

Peru Rail’s 07:42 Expedition service from Poroy/Cusco to Machu Picchu Peublo/Aguas Calientes, Peru. August 14, 2015.

Poroy/Cusco To Machu Picchu Peublo/Aguas Calientes || The Ching Ching Train

The rail line between Poroy/Cusco & Machu Picchu Peublo, the latter also known by its old name of Aguas Calientes, is the quicker, more comfortable way to get to Machu Picchu. It’s also cheaper than the Inka Trail option, but that doesn’t mean it’s cheap (whatever way you decide to get to Machu Picchu it’ll put a dint in your coffers doing so & you best be prepared to book everything – from the train tickets to accommodation in Machu Picchu Peublo to the entrance tickets for Machu Picchu itself – well in advance). Oh no. In fact, per distance travelled these rails are – ching ching – the most expensive in the world. Three train companies service the route although only one, Peru Rail, services the full 92 kilometer Poroy/Cusco to Machu Picchu Peublo stretch, and it does so with three service/class options – Expedition, Vistadome & Hiram Bingham. The return Poroy/Cusco-Machu Picchu Peublo-Poroy/Cusco trip cost me US$170, a bargain really considering you can pay up to US$795 for the Orient Express-esque Hiram Bingham service that plies the same stretch of shockingly overpriced twin gauge. Ok so the sting is somewhat lessened by the awesome service on board – the affable, attentive staff actually make you feel welcome, actually make you feel special – & the views from the spotless, comfortable, airy, & vista-promoting carriages.

Carriage D of Peru Rail’s 07:42 Expedition service from Poroy/Cusco to Machu Picchu Peublo/Aguas Calientes. The train rarely gets out of first gear as it meanders out of Poroy and on towards the so-called Sacred Valley, an immensely steep-sided & picturesque river valley that was well exploited agriculturally by the Inacs and where they built many of their citadels, the most famous of which is obviously Machu Picchu which sits at the western end of the narrow valley, (way) too narrow to access by road. I had plenty of time to take pictures of the surrounding scenery but the pictorial highlight of the trip for me was the carriage I rode in, seen here as captured via the HRD function of my camera. Carriage D of Peru Rail’s 07:42 Expedition service from Cusco to Machu Picchu Peublo/Aguas Calientes, Peru. August 14, 2015.

– The Rough Guide to Peru

Unlimited tea & coffee on board this morning’s Expedition service from Poroy/Cusco to Machu Picchu Peublo was, ahem, ‘free’ but a beer set me back SOL7 (€2). I couldn’t resist, even at 10 a.m. Refreshments in carriage D of Peru Rail’s 07:42 Expedition service from Poroy/Cusco to Machu Picchu Peublo/Aguas Calientes, Peru. August 14, 2015.

Machu Picchu Peublo/Aguas Calientes

The end of the line. Officially called Machu Picchu Peublo but still known by its old name of Aguas Calientes, this town/village, a 25-minute bus ride or 2 hour walk from Machu Picchu itself, is here solely to service the droves of tourists that descend on Machu Picchu daily, some 3000 in high season, or right about now. Sandwiched between towering peaks & utilising every available piece of vertigo inducing land, it’s chock-a-block with hundreds tourist-related outlets & services – hotels, restaurants, bars, cafes, & souvenir shops, all selling the same Inca-related tourist tat. Machu Picchu Peublo/Aguas Calientes, Peru. August 14, 2015.

Machu Picchu Peublo/Aguas Calientes, Peru. August 14, 2015.

A market stall in Machu Picchu Peublo/Aguas Calientes, Peru. August 14, 2015.

On of the many Machu Picchu tourist buses on the narrow streets of Machu Picchu Peublo/Aguas Calientes, Peru. August 14, 2015.

Needless to say, Machu Picchu Peublo/Aguas Calientes is a convenient base to ensure an early morning start for a day of traipsing around the terraces of Machu Picchu; it’s the only reason the place exists. My alarm is set for 4:30 a.m., breakfast is at 5 a.m., & I’ll be on one of those Machu Picchu-bound tourist buses shortly thereafter. Best get to bed so. I’ve a BIG day tomorrow.

MACHU PICCHU

Date || August 16, 2015

Location || Cusco, Peru ( )

)

And so it is done. A decade+ long itch to espy South America’s most famous attraction has been scratched. Yes, I have finally laid my oculi on fabled Machu Picchu. And now that I have I will no longer have to promise myself, & when seeing that picture of the Inca Empire’s most famous ruins, that I’ll see it for myself someday.

OK, let’s get this picture of Machu Picchu out of the way first. Yes, it’s that Machu Picchu picture that’s everywhere, an overview of the 10 hectare (1,000 acre) site as seen from above the the so-called East Agricultural Sector. Towering over the northern end of the site is the famous sacred peak of Waynapicchu (2,682 metres) &, further still in the distance, the forested peaks spiking up from deep valleys & a distinctive U-curve in the Urubamba River. Captured in gimmicky Toy Camera mode for a little twist on the Machu Picchu shot every man & his dog captures. Machu Picchu, Peru. August 15, 2015.

Machu Picchu

The true origins of Piqcho – known by its more popular name of Machu Picchu, meaning Old or Ancient Mountain & the name of the peak the citadel was built upon – are a mystery but it was believed to have been built as a royal hacienda (estate) for Inca Emperor Pachacutec during his reign (1438-1471). It’s also speculated that the site was the best preserved of many Inca agricultural centres found in the Sacred Valley of the Incas, sites that served Cusco when in its prime. The settlement’s location, halfway up the Andes Plateau atop a granite-heavy, 2,430-metre-high peak & deep in the Amazon jungle above a bend in the Urubamba River, is nothing short of stunning. It’s widely believed that the site was abandoned by the Incas because of a smallpox breakout after the Spanish defeat of the Inca Empire, but the site’s remoteness meant it was never actually discovered, & thus plundered, by the Spanish conquerors. This coupled with the site’s high quality stone constructions meant it survived relatively intact until it was rediscovered by American archaeologist Hiram Bingham on July 24, 1911 (although a Spaniard by the name of Diego Rodriguez de Figueroa did pass the site in May 1565, believed the first foreigner to do so). Guided by local 11-year-old boy, Bingham was the first post-colonial era non-local/foreigner to arrive at the site – until then it was a secret known only to local peasants. Today, over a century after its rediscovery, Machu Picchu is easily South America’s best known archaeological site & probably the continent’s most iconic tourist attraction. Awarded Mixed Site World Heritage status by UNESCO in December 1983, a denomination shared with only two other locations in the Americas, the site is besieged by upwards of 3,000 visitors a day, a number that, and although capped to help preserve the ruin and its surrounds, makes it a busy place to be.

A (very) early start to the day saw me arriving at the Machu Picchu complex shortly after the sun rose above the peaks surrounding the site. I stood on one of the steps of the site’s massive terraces in the Eastern Agricultural Sector near the main entrance watching the lighting slowly change as the sun rose higher into the (almost) cloudless, deep-blue sky. It was a magical, serene experience. Watching sunrise from the terraces of the Eastern Agricultural Sector of Machu Picchu, Peru. August 15, 2015.

– UNESCO commenting on the Historic Sanctuary of Machu Picchu

Shortly after sunrise on the terraces of the Eastern Agricultural Sector in Machu Picchu, Peru. August 15, 2015.

Early morning in Machu Picchu, Peru. August 15, 2015.

Machu Picchu was built in two distinctive sectors, agricultural & urban. The urban sector is U-shaped and has two immense architectural groups with streets, stairwells, & a network of water canals suitable for both domestic & irrigation use, all of which are interspersed with small squares & courtyards. The constructions in Machu Picchu have rectangular floor spaces with many of the enclosures – called masmas & organised into neighbourhoods, each with a specific purpose – having only 3 walls which at one time were all thatched. This is a picture of one of the loftier Machu Picchu stone constructions, the Guardhouse, which offers great views down over the site & is passed en route to Montana Machupicchu. Machu Picchu, Peru. August 15, 2015.

At the summit of Montana Machupicchu. Machu Picchu, Peru. August 15, 2015.

Montana Machupicchu

Entrance tickets to Machu Picchu are a hot commodity, and no mistake. Aside from a daily quota of general admission tickets, a limited number of admission tickets are also sold which allow visitors to scale one of the two prominent peaks overlooking the site – the aforementioned Waynapicchu (2,682 metres) at the northern end of the site & the loftier Montana Machupicchu (3,061 metres) towering over the southern end of the site. Securing myself a Machu Picchu + Montana Machupicchu ticket meant I didn’t have to wait another 3 days for the next available general admission ticket, not to mention providing me with an outlet for escaping the crowded terraces of Machu Picchu itself for a different if somewhat distant overview of the architectural ruins & their splendid setting. Indeed, the (at times) strenuous 2.5 hour round trip hike up & down Montana Machupcchu was to prove to be the highlight, no pun intended, of my visit to the Machu Picchu environs.

An Inca flag marks the 3,061-metre summit of Montana Machupicchu overlooking Machu Picchu, Peru. August 15, 2015.

Overlooking Machu Picchu from the trail to the summit of Montana Machupicchu. Machu Picchu, Peru. August 15, 2015.

The Machu Picchu ruins contain more than 100 flights of stone steps that interconnect the various palaces, temples, storehouses & terraces, the latter of which is probably the site’s most spectacular feature – huge terraces slice across ridiculously steep mountainsides as seen here in this view of the massive terraces of the site’s Eastern Agricultural Sector. In the distance is the pointy summit of Montana Machupicchu from where I had just returned, it so distant that the massive Inca flag marking its summit barely visible in this view from the archaeological site itself. The terraces of the Eastern Agricultural Sector in Machu Picchu, Peru. August 15, 2015.

The terraces of the Eastern Agricultural Sector are a favoured hangout for Machu Picchu’s ever-present llamas. Needless to say they are a huge attraction for the camera-toting masses, especially the baby llamas. Machu Picchu, Peru. August 15, 2015.

An example of rectangular convex style stonework of the site’s main temple, the Temple of the Sun, a semi-circular, stunted tower-like structure that displays some of Machu Picchu’s finest granite stonework – the Incas were renowned for their astonishing stonework with which they constructed structures without the use of any mortar. Machu Picchu, Peru. August 15, 2015.

– The Rough Guide to Peru

OK, so I’m calling the Rough Guide out on this one. Words can describe Machu Picchu. In fact, only one word is needed – overhyped. The setting? Yes of course it’s stunning, the highlight of the site for me (the Incas chose well). But I’ve been blessed and have seen some pretty nice parts of the world. The Inca stonework? In my opinion it’s better elsewhere, Ingapirca in southern Ecuador, for example, somewhere that doesn’t attract the crowds & thus isn’t the over-commercialised tourist circus that Machu Picchu is. Don’t get me wrong – I enjoyed the day I spent at the site, but I left it feeling I was glad it was over, glad that particular box had been ticked so that I now no longer have a desire to go there. For me Machu Picchu was an ordeal. I understand the need to limit the numbers of daily visitors at the site, and in a way I don’t even blame the Peruvian government for doing as they do, namely exploiting everything about their prize draw to the max – from getting to Machu Picchu to being in Machu Picchu to getting away from Machu Picchu is an exercise in financial damage limitation. I get all of that. I really do. But unfortunately there is no denying that Machu Picchu is a victim of its own success. Why it garnered the success I’ve really no idea (actually, I suspect it’s a combination of the site’s location, the mystery surrounding it & its well-preserved nature) but that’s neither here nor there. I’ve been looking at pictures of Machu Picchu for years now. Decades even. I’ve always wanted to go. South America for me was Machu Picchu. But pre-arrival I suspected the site couldn’t possibly live up to the hype – it didn’t – & I also suspected that it would underwhelm – it did. For me Machu Picchu was like your typical Christmas, with the anticipation & build-up proving way more enjoyable than the main event.

PERUVIAN LAKE TITICACA REGION

Date || August 21, 2015 Location || Puno, Peru ( )

)

Wow. This Lake Titicaca region is immensely scenic & immensely photogenic. I mean immensely photogenic. I’ve already spent more time here than initially planned but I think I’ll have to stick around here for a few more days.

Locals on the floating Uros Islands in Lake Titicaca, Peru. August 19, 2015.

I’ve spent four nights here now gasping for breath – both the altitude & the scenery has taken my breath away – on the Peruvian side of the world’s highest alpine lake; three on the shores of the lake and one on an small remote island, Isla Taquile, some 30 kilometres offshore. All I’ve seen are shimmering blue waters & fluffy, blindingly-white clouds set against deep-blue skies. Add to the mix colourfully dressed, lake-inhabiting local Indians, some of whom bounce around on floating man-made reed islands, and you’ve got quite the combination. It may just be one of the most photogenic parts of the world this traveller has ever visited. My camera has been busy, and I’m not even done with Lake Titicaca yet.

A traditionally dressed local boy overlooking Lake Titicaca from the main square of Taquile Island, Peru. August 20, 2015.

Lake Titicaca

The name Titicaca is an Aymara word – Aymara being the second-most widespread indigenous language of the Andes after Quechua, the language of the Incas – meaning ‘Puma’s Rock’, a reference to an unusual rock found on Titicaca’s Isla del Sol (Island of the Sun). High in the Andes on the border with Peru & Bolivia, it is the world’s largest high-altitude body of water & South America’s largest lake (Lake Maracaibo in Venezuela, while bigger, has a direct connection to the sea so is ruled for not actually being a lake). Sitting at an altitude of 3,827 metres, Titicaca is an 8,400 km² body of shimmering blue water that’s almost 300 metres deep at its deepest point. Since 1978 the whole Titicaca region has been a National Reserve, one that sustains many varieties of birds & native fish. Oh, and as already mentioned, it is a pretty photogenic region – enclosed by white peaks, the lake’s usually placid and mirror-like waters are adept at reflecting both its the surrounds & the sky back on itself.

Boating on Lake Titicaca outside Puno, southern Peru. August 20, 2015.

Puno

I’ve spent my time here skirting the lake and boating across it, all the while based in the somewhat grubby but likable Peruvian town of Puno.

Parque Pino in Puno on the shores of Lake Titicaca, Peru. August 19, 2015.

Situated at the northern end of the lake, Puno is Titicaca’s largest settlement and port. There’s not a whole lot to see in the town itself; most, & I was no different, use the town as a base for exploring Titicaca’s delights, namely its offshore islands – both the solid, natural ones & the floating, man-made ones – & the unusual tower-like burial chambers of the pre-Inca civilisations who called this stunning part of the world home way back when.

Titicaca Villages, Tourism & the Humble Spud

The villages that surround & inhabit the the islands of Lake Titicaca depend on grazing livestock for a living since the altitude limits the growth potential of most crops. That said, this region is still predominately a self-sufficient agricultural economy. As such the whole of steep-sided Taquile Island, for example, is covered with significant amounts of terracing where the islanders grow maize, corn, wheat, barley, potatoes, broad beans, & quinoa, a grain crop that originated in the Andean region of Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, & Colombia and one that was first domesticated for human consumption here some 3,000 to 4,000 years ago. In fact, it is this Titicaca region of South America where the domestication of a number of very important plants, including the humble potato, first took place – you can add the tomato & the common pepper to that list, too. It’s no wonder I like it here.

A llama enjoying sunset, although not the attention of photographers, on the shores of Lake Titicaca, Peru. August 19, 2015.

Sillustani

Inhabited well before the arrival of the Incas, the Titicaca region is home to curious, ancient & gargantuan stone tower-tombs known locally as chullpas. The region is dotted with the tall cylindrical towers, often standing in battlement-like formations & measuring up to 10 metres in height, burial chambers of the Colla tribe who dominated the region before the arrival of the Incas.

Sillustani is a little peninsula in Lake Umayo, a small body of water not far from Lake Titicaca itself and about 30 kilometres north of Puno. The 500-year-old chullpas here, over 100 in total, vary in size and condition, most having succumbed to earthquakes and tomb robbers over the years. The stonework of the towers/tombs vary too, the earlier ones a more unrefined honeycombed style while the newer ones display more elaborate, higher-quality stonework influenced by the advance of the Incas. However, and as impressive as the towers were, it was the location that got me – standing on a rocky peninsula of land jutting out into a gorgeous body of water while surrounded by 500-year-old tomb towers as the late afternoon sun did its thing was magical. Just magical. A chullpa, an ancient stone burial tower, on the Sillustani peninsula overlooking Lake Umayo, southern Peru. August 19, 2015.

Titicaca Islands

There are over 70 islands in total in Lake Titicaca, the largest being the Isla del Sol (Island of the Sun), an ancient Inca temple site on the Bolivian side of the border (it’s accessed from the Bolivian town of Copacabana, my next stop). From my base Puno, I embarked on a trip to the nearby Uros Islands & to the somewhat further afield Taquile Island. One is man-made, one by the grace of god. Both, and as I have already mentioned, are extraordinarily photogenic.

The floating Uros Islands in Lake Titicaca, Peru. August 19, 2015.

Titicaca Islands – Uros Islands

The Uros Islands are quite unique, floating platforms made from layer upon layer of totora reeds, the dominant plant in the shallows of Titicaca – the reeds are quite versatile as they are also a source of food as well as the basic material for roofing, walling & lake-going vessels (fishing rafts, tourist boats etc.). A major tourist attraction, the 600 or so Uros people who live on the some 50 floating islands, which sometimes move about the surface of the lake, used to be a proud fishing tribe but these days they are totally dependent on tourism for income. They have been living this way for centuries, when they first retreated to the sanctuary of the lake’s waters from more powerful neighbours like the Incas. Life here, while unique, isn’t easy; large distances are travelled to find fresh water & the islands themselves, each of which take about 2 months of communal work to produce & which has a shelf life 12-15 years, rot from the bottom up very rapidly meaning fresh matting has to be added almost constantly.

A welcome committee approaching one of the floating Uros Islands. Visitors are welcomed to and from the islands by a singing grouping of ladies (always ladies) who inhabit it – each of the islands, depending on their size, are home to approximately three to eights families. On any visit to the islands, visitors are briefed on island construction techniques by a male, always a male (basically it’s layer upon layer of reeds atop the reed foundation), before being shown the inside of one of the island’s huts, made from reeds of course. Then you’re subjected to the hard sell of trinkets (bracelets, necklaces etc.), mats, pillowcases, blankets & miniature island figurines, huts & boats, the latter of which are all made of reeds of course. It’s hard not to succumb & buying something really does make a difference considering the islands and their inhabitants rely totally on trade with tourists for a living. But once that’s out of the way you’re free to ‘explore’ the island you’re on – it’s a lot of fun bouncing around on the springy bed of reeds. The floating Uros Islands on Lake Titicaca, Peru. August 19, 2015.

Taking a brief trip on the waters of the lake aboard a reed boat is an optional extra on any visit to the Uros Islands. Even here photo opportunities abound. A boatman on the Uros Islands, Lake Titicaca, Peru. August 19, 2015.

I knew I brought to book to South America for a reason. A parting shot of the Uros Islands when boarding the boat to return to the mainland. We were seen off by the same singing welcoming committee, one I thought looked familiar. The floating Uros Islands, Lake Titicaca, Peru. August 19, 2015.

Titicaca Islands – Isla Taquile

Titicaca island number 2 was Taquile Island, a small (it only measures 7 kilometres long by 1 kilometre wide) but hilly non-floating Titicaca island some 30 kilometre offshore of Puno. Accessible via a 3 hour (slow) boat ride from Puno, there is a real absence of the 21st century here, not to mention electricity, on the island, home to 1200 local Indians & somewhere where traditional lifestyles prevail to this day give a genuine taste of pre-Conquest Andean Peru.

Taquile Island, while nowhere near as touristy as the more accessible floating Uros Islands, does generate a form of income from tourists who make the effort to visit, mostly by selling fine alpaca wool products – most of the island’s female inhabitants are expert weavers & knitters & seeing local women sitting around weaving is all part of the Taquile experience. This is a picture of island locals sitting outside a weaving market in the main square of the island, about as close to tourist central that you’r going to find on Taquile. Taquile Island, Lake Titicaca, Peru. August 20, 2015.

A girl & sheep on path on Taquile Island, Lake Titicaca, Peru. August 20, 2015.

This little girl, typifying my vision of a dirty urchin, was a member of the family I roomed with on Taquile Island. She was adorable and not one bit shy around tourists. Taquile Island, Lake Titicaca, Peru. August 21, 2015.

Locals descending to the port on Taquile Island to catch the boat back across the calm waters of Lake Titicaca to the Peruvian mainland seen in the distance, a 3 hour trip. Yes, the boats around here are in no kind of hurry. Taquile Island, Lake Titicaca, Peru. August 21, 2015.

Moving On

I’m done with Peru but not Lake Titicaca. I’m comfortable here in this region – it must be the scenery, the weather (the burning daytime sun & chilly evenings aside), or its ties with the spud. Either way I’m staying by the lake for a few more days, albeit on the Bolivian side of the nearby Peru/Bolivia border (it’s some 2 hours bus ride from Puno). I’ll be crossing over the border tomorrow and thereafter it’ll more of Lake Titicaca’s splendors, albeit in a different country, Bolivia, South American country number 5.

PERU-BOLIVIA BORDER ISSUE

Date || August 22, 2015

Location || Copacabana, Bolivia ( )

)

T’was eventful crossing border from Peru to Bolivia earlier today. I almost didn’t make it. Entering Bolivia wasn’t the problem. It was leaving Peru that made things interesting. Seemingly I was only granted 5 days when entering Peru 26 days ago, something I hadn’t even noticed until today (it was there in my passport for all to see). That’s a 21-day overstay. The Peruvian Immigration officer couldn’t explain it (as an Irish/EU passport holder I should have been given 90 days as standard, no questions asked) but had no option but to ‘fine’ me a total of USD$21 payable only in a nearby bank. But today is Saturday. Banks don’t open on weekends. The official said the ‘problem’ could go away if I paid the equivalent of €30 direct to him. I wasn’t happy. I said OK (what choice did I have) but was wary when he refused to provide a receipt. He didn’t like me from that point onward & gave me back my passport with a deposit slip, totalling $21, for the aforementioned nearby bank. There was a total absence of officialdom on either side of the helter-skelter border, marked only by a crude arch, beyond which is the sign seen in the below picture. So I, & being as stubborn as I am, tried to enter Bolivia without a Peruvian exit stamp – bizarrely you could easily exit Peru & enter Bolivia without checking out of one & into the other, such was the chaotic crossing. That didn’t work (the first thing the Bolivians checked for was a Peruvian exit stamp) so I hoofed it back to the Peruvian hut, tail firmly between my legs, to pay the €30 and be on my way. But it wasn’t that easy. If only. The Peruvian Immigration official now refused to deal with me. He waved his finger. A lot. He kept saying ‘banco’ (bank) & ‘Lunes’ (Monday). I’d clearly burnt my bridges. Big time. I was in a pickle. I pleaded with him, not losing sight of the fact that I was pleading with him to accept payment, without exchange of receipt, to let me OUT of his country. He kept waving his finger. I’d no choice but to go on the charm offensive. I told him I liked his country (I did) & that Peruvians were really nice people (most of them.. my limited Spanish vocabulary meant I used the word ‘beautiful’). He kept waving his finger. I told him I’d spent a lot of money in his country (yes, that too). He kept waving his finger. I said I was sorry and asked for his help. He kept waving his finger. Impasse. I was set to explode but had limited options but to keep calm, keep smiling, keep grovelling. My vocabulary exhausted, I scoured my Spanish phrasebook for nice things to say & kept chipping away. Chip…. chip…. chipping away. I eventually got a smile out of him. He was melting. I was winning. I kept going. Finally, voila, the finger waving stopped. I kept going & eventually he asked for my passport, eventually took my money, eventually didn’t give me a receipt for the €30 I gave him, and eventually I was stamped out of Peru. We parted on good terms, a handshake confirming no hard feelings; according to him he was just doing his job and unknowns to him I was just being me. After that, and back in the Bolivian hut (it was barely a hut), it was plain sailing – I was stamped into the country without having to pay the USD$50 the South African travelling with me had to pay or the – ouch – USD$160 each the two Americans we were crossing the border with had to pay. Yes, holding an Irish passport generally makes crossing international borders a painless endeavour, unless things don’t quite go to plan AND you happen to be a stubborn fool like me. In that case things get a little more interesting, and little more expensive, just like they did today. Well hello Bolivia!

Hello Bolivia. A rushed picture captured on my third crossing of the blink-and-you’ll-miss-it Peruvian-Bolivian Kasani border crossing by the shores of Lake Titicaca, some 8 kilometres from the Bolivian town of Copacabana. My first crossing was after initially passing the Peruvian Immigration hut (easily missed), second crossing was en route to an attempt to enter Bolivia sans Peruvian exit stamp, & third crossing was having successfully grovelled my way out of Peru. At the Peruvian-Bolivian Kasani border crossing on the shores of Lake Titicaca. August 22, 2015.