China (2015)

Recapping A Sixth Visit To Mainland China – With Stops In Beijing, Harbin & Urumqi – En Route To Central Asia

The Bird’s Nest, Beijing, China. February 5, 2015

China 2015 (February 3-12 2015)

My sixth visit to China was yet another passing through affair, this time en route to pastures new in Kazakhstan & Central Asia. To get there, & between time spent covering larges distances on various trains, I spent a few days on familiar ground in Beijing; I paid a visit to Harbin, in northeastern Heilongjiang province, for its annual International Ice and Snow Sculpture Festival; And I passed through the world’s largest city furthest from a sea or ocean, Urumqi in the autonomous northwestern Xinjiang province, en route to, and not far from, the border with Kazakhstan.

Read all postings from the road in chronological order or jump to specific postings using these links.

Beijing || Harbin || RIDING THE RAILS – Harbin to Beijing, Beijing to Urumqi || Urumqi

Archived Postings From The Chinese Road (In Chronological Order)

Date || February 4, 2015

Location || Beijing ( )

)

The sun shone a lot today. It was beautiful, a lovely day to walk around Beijing, China. Being as familiar with this city as I am meant I didn’t have much I wanted to see today but I kept busy regardless. Although I was on familiar ground it was good to be out and about with a camera in hand.

Hustle & bustle in the popular lanes of the Wangfujing district of Beijing. Busy with tourists & locals alike & alive most hours of the day, but especially at night, this is where you come to find such delicacies as fried scorpion, spiders, snakes, cockroaches and whatnot on a skewer (mostly dead). Yes, & their growing affluence aside, the Chinese will (still) eat anything and some foreigners will, too. Me? No chance. Beijing, China. February 4, 2015.

A guard in Tiananmen Square fronting the Tiananmen Gate, or Gate of Heavenly Peace, the entrance to the Place Museum, a.k.a. The Forbidden City. Tiananmen Gate is one of the symbols of China – it appears on the Chinese National Emblem. First built in 1420, the gate is 66 metres long, 37 metres wide and 32 metres high. It serves as the entrance to the Imperial City, which is the location for Beijing’s famous Forbidden City. It was from Tiananmen Gate, on October 1st, 1949, that Chairman Mao, the leader and co-founder of the Chinese Communist Party & whose massive portrait famously hangs from the gate, delivered his liberation speech, declaring that “the Chinese people have now stood up”. Mao, who you can read more about from my 2004 entry from Beijing, was addressing his subjects situated in Tiananmen Square, the famous square of the same name that the gate overlooks. One of the largest public squares in the world, it is infamous as the site of many mass movements, most famously in 1989 when students and workers peacefully protesting for democracy and against corruption & oppression were savagely suppressed. The guard here is just one of many all over Beijing. It seems like one can’t walk 100 yards without encountering a security check. What they are securing against I’ve no idea. It’s more people management than people security. Oh China. Beijing, China. February 4, 2015.

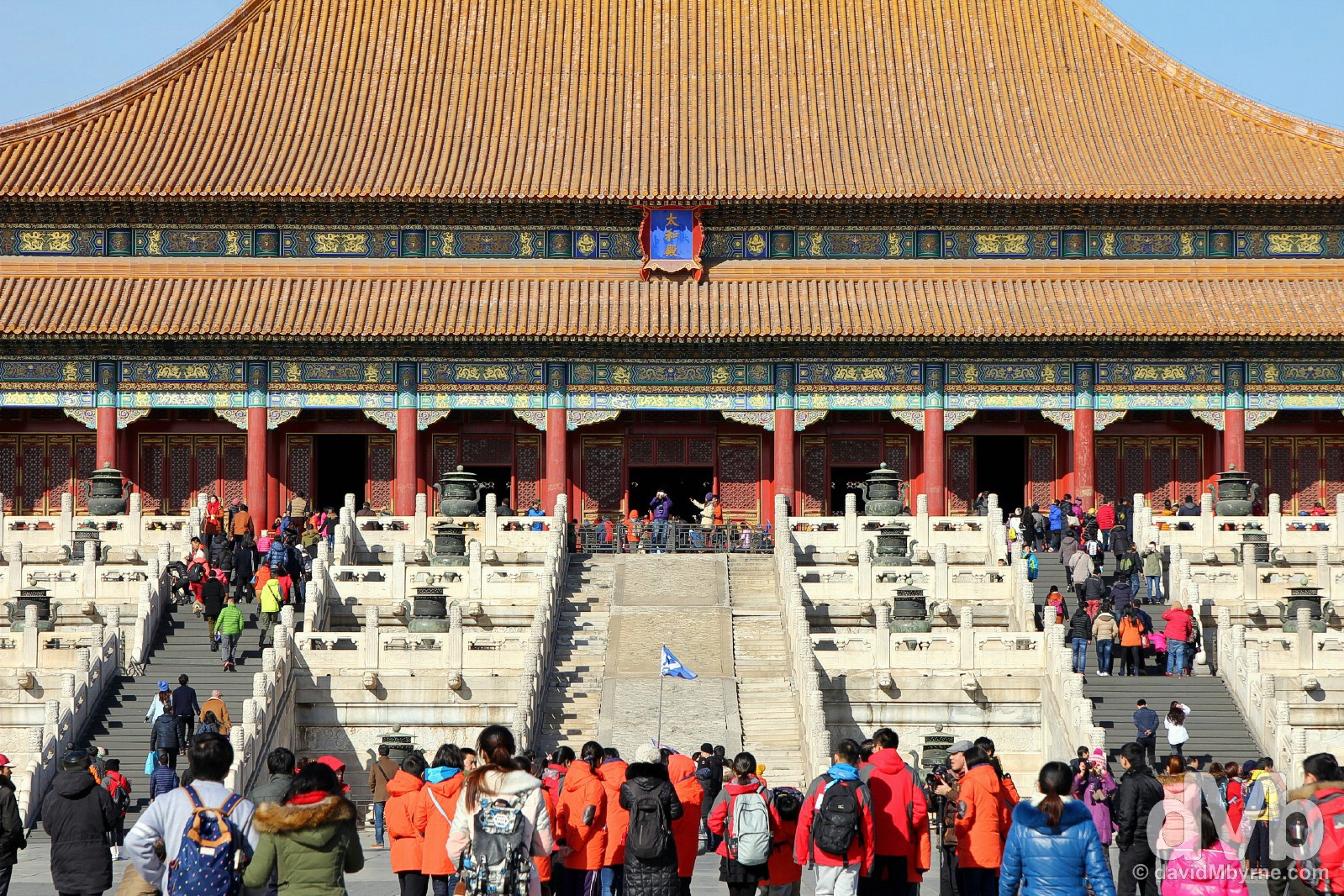

I hadn’t been here since my very first visit to Beijing back in 2004 so I decided to pay a visit to the so-called Forbidden City, now officially known as the Palace Museum. Located in the middle of Beijing off of the equally famous Tiananmen Square, the Forbidden City was built between 1406 and 1420 and was the Chinese Imperial palace from the mid-Ming Dynasty (1368 – 1644) to the end of the Qing Dynasty (1644 – 1911). It’s a vast complex consisting of 800 buildings housing over 8,800 rooms and covering an area of over 7 km². It was declared a World Heritage Site in 1987 and is listed by UNESCO as the largest collection of preserved ancient wooden structures in the world. It was called the Forbidden City because it was forbidden for the average citizen to even approach the walls of the city in the days of the various dynasties. No such issues these days as anyone can wander around taking in its grandeur. This is a picture of the hordes in the courtyard fronting the Tai He Dian (Hall of Supreme Harmony), the first & main hall of the three major halls of the outer court of the Forbidden City. Beijing, China. February 4, 2015.

– UNESCO commenting on Imperial Palaces of the Ming and Qing Dynasties in Beijing and Shenyang

Buildings in the Place Museum, a.k.a. The Forbidden City, in Beijing, China. February 4, 2015.

The inner courtyard of the Lu Song Yuan Hotel, my home on this, my 6th visit to Beijing. The hotel itself was nothing to write home about but its traditional central courtyard was certainly photogenic (and it proudly displays a ‘The Most Distinctive Courtyard’ award, dated June 2009, from the Beijing Dongcheng Tourism Industry Association). The hotel is located in a traditional hutong, a narrow, residential lane synonymous with poverty, bad plumbing and decay. This hutong, Banchang Hutong, which has survived the modernising wrecking ball, is 457-metres long & 6-metres wide and its claim to fame is that No. 19 once housed the embassy of DPRK, a.k.a. North Korea. So there. Lu Song Yuan Hotel, Banchang Hutong, Dongcheng District of Beijing, China. February 4, 2015.

Date || February 5, 2015

Location || Beijing ( )

)

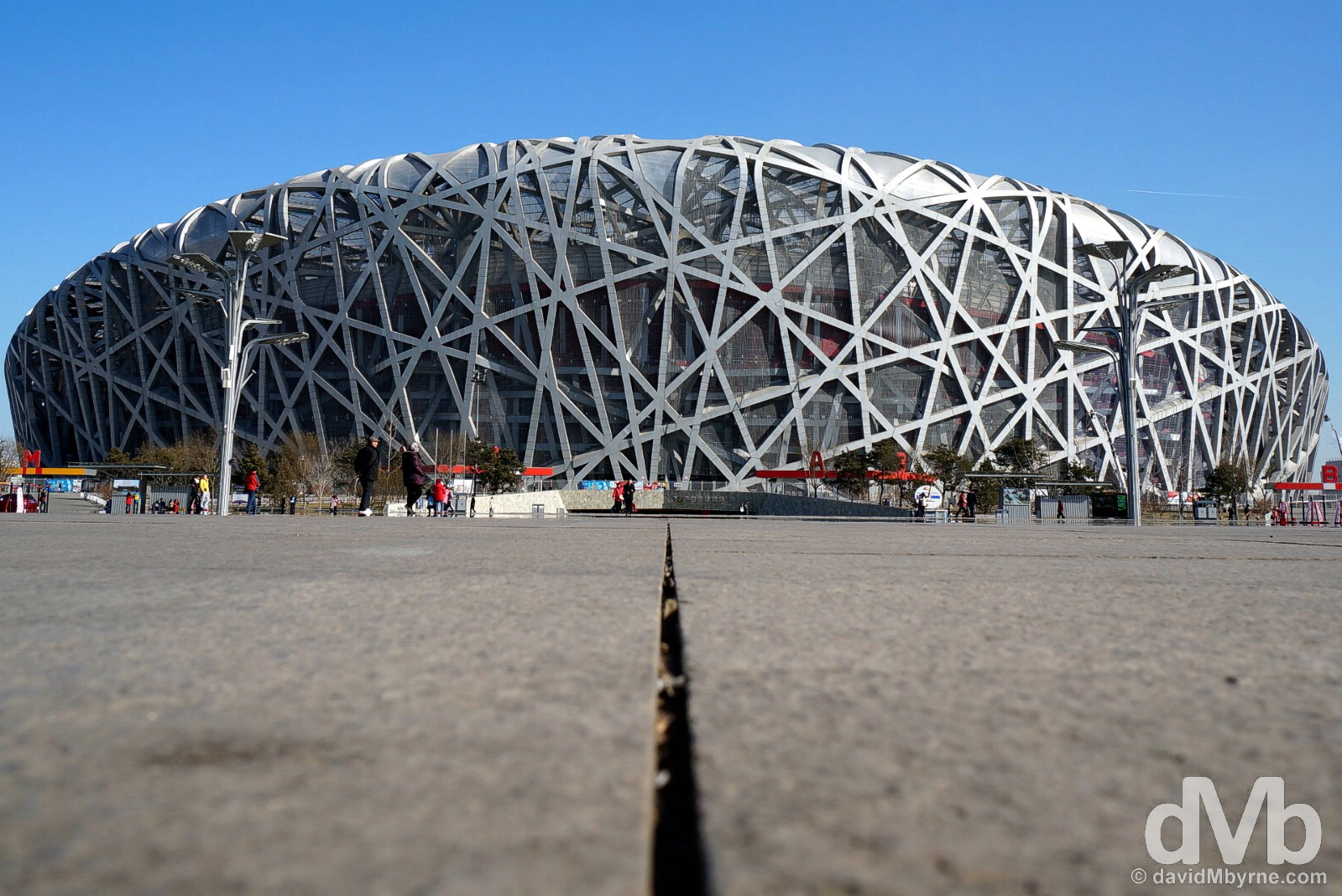

Beijing’s Olympic Park housed the main venues for the 2008 Beijing Olympics & Paralympics, the XXIX Olympiad & the so-called ‘Green, Hi-Tech & Humanistic Olympics’. It didn’t surprise me to learn that the almost 12 km² site, wasteland prior to redevelopment for the games, is the largest development ever for an Olympic games – trust the Chinese to make a statement. The park boasts, among other things, a massive dragon shaped waterway, a huge conference center, the National Indoor Stadium, numerous shiny sculptures & gardens, a temple, hotels, a shopping centre, and more than a few space age-looking towers & buildings. According to the onsite information boards, the whole shebang ‘blends together both traditional & modern architectural elements’. Maybe it does but, and only 6+ years after the event it was built to accommodate, the park already feels and looks, to me, tired and dated; it’s a vast space, so vast that the whole area feels soulless, void of any character. I peered at the site through construction railings some distance away on my February 2008 visit to Beijing, some 6 months prior to the games, when the whole site look far from finished. Today I ponied up the guts of €11 (CNY80) to snoop around the innards of the site’s two main attractions – the confused looking National Stadium, a.k.a. the Bird’s Nest, & the bouncy looking National Aquatics Centre, a.k.a. the Water Cube – and left the park convinced that both look way better from the outside (& from a distance), especially on a beautiful day just like today.

The main body of the National Stadium, a.k.a. the Bird’s Nest, is a colossal saddle-shaped elliptical steel structure weighing some 42,000 tons. The stadium is 333 metres long, 298 metres wide and 69 metres tall and can seat 91,000 spectators. A modern-day Beijing landmark with a unique interwoven architectural appearance, construction started with a groundbreaking & cornerstone laying ceremony on December 24, 2003, but it wasn’t officially completed until August 8, 2008, mere days before the Olympic’s Opening Ceremony. The National Stadium, a.k.a. the Bird’s Nest, in Beijing Olympic Park, Beijing, China. February 5, 2015.

Walking past the National Aquatic Centre, a.k.a. the Water Cube. This place hosted the 2014 APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation) Economic Leaders’ Meeting on November 10th & 11th last and even today, some 3 months later, the place is still setup as such – one can still pay to have their picture taken on the stage, placed on top of the Olympic pool & in front of the APEC sign, where the likes of Barack Obama, Vladimir Putin & Stephen Harper stood. Given that, I assume this place doesn’t actually get utilised much as an aquatics center. Beijing Olympic Park, Beijing, China. February 5, 2015.

Date || February 6, 2015

Location || Harbin ( )

)

Harbin started life as a small fishing village on the Songhua River, frozen solid when I was in town, as was I. It’s far from small now. It’s massive. The city’s population swelled with the influx of Russians – firstly those building a railway line & secondly those fleeing the Russian Revolution – & with a present-day population of over 10 million, Harbin is China’s 6th most populous city, easily the largest urban centre in northeastern China, & the last city of any note prior to hitting the unforgiving sub-Siberian wilderness.

I stepped off the overnight train from Beijing earlier this morning. It was just after 9 a.m. & cold – -19 degrees Celsius I believe – but bearable; I have experienced colder on my travels & I’m well prepared for it, as one should be travelling here this time of year. I wanted to spend two nights here (why, I don’t know) but the language barrier meant I failed to change my train ticket shortly after arrival. Even when standing at the ‘Change Ticket’ window I was met with a stone-faced ‘no’ and an accompanying shake of the head. I may still be in China but I can tell Russia isn’t too far away.

So Harbin was to get one day & one night of my time before returning to Beijing in the morning. That day is done, the night almost so. Here’s what I got up to.

Zhongyang Dajie/Street (Central Avenue)

While Harbin is mostly a massive, sprawling, typically Chinese city full of sterile blocks & skyscrapers, parts of it have retained the look of the past when the Russians were around. Nowhere is this more in evidence than on the pedestrised shopping street of Zhongyang Dajie in the heart of the city, the first such street in China & a little bit of St. Petersberg, Russia, lifted right into downtown Harbin.

The entrance to Harbin’s pedestrianised Zhongyang Dajie, a.k.a Central Avenue. The street, restored & cobblestoned as part of a 1998 beautification effort, is dotted with with European-style, pastel coloured buildings reflecting the most influential architectural styles of the day – Renaissance, Baroque, Eclecticism & Art Nouveau styles are all represented. Seventeen buildings along its 1,450-metre long stretch have been granted historic status (a plaque on the street claims it to be an open-air Architectural Arts Museum) with each building displaying a plaque detailing its history as either a colonial home &/or business. Harbin, China. February 6, 2015.

Russian Orthodox Cathedral

There isn’t a whole lot to do or see in Harbin and if you’re here anytime of the year other than in the depths of winter for the various ice treats the city serves up then this, the Cathedral of the Holy Wisdom of God, a.k.a. the Russian Orthodox Cathedral or formally St. Sofia’s, is probably going to be top of your must-see list. Boasting probably the most famous onion domes in China, this is Harbin’s finest sight (so says Rough Guides).

An obvious remnant of Harbin’s Russian past, the redbrick Russian Orthodox Cathedral, formally St. Sofia’s, was built in 1907 after the completion, in 1903, of the Trans-Siberian Railway which connected Vladivostok in Russia, not too far from here, to northeast China. It’s not a particularly large church but it was big enough to serve the some 100,000 Russians who lived here in the 1920s, a third of the city’s population at the time. It was closed for good following the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 (the victorious Communists outlawed Christianity). It received First class Preserved Building status in 1996 and in 1997 its interior was turned into a museum, the SO-CALLED Harbin Art & Architecture Centre. The Cathedral of the Holy Wisdom of God, a.k.a. the Russian Orthodox cathedral or formally St. Sofia’s, in Harbin, China. February 6, 2015.

The Harbin Art & Architecture Centre inside the compact, musty interior of Harbin’s 1907 Russian Orthodox cathedral is nothing more than a collection of old photographs from Harbin’s past stretching back to the days when the city served as a Russian railway outpost. Harbin, China. February 6, 2015.

I love this. This guy, who looked remarkably like Psy, was really pushing the selfie boat out and I spent quite a few minutes watching him trying to get it right. At least he didn’t have one of those selfie sticks (although unfortunately they are still here in China). Selfie time in front of the Cathedral of the Holy Wisdom of God, a.k.a. the Russian Orthodox cathedral or formally St. Sofia’s, in Harbin, China. February 6, 2015.

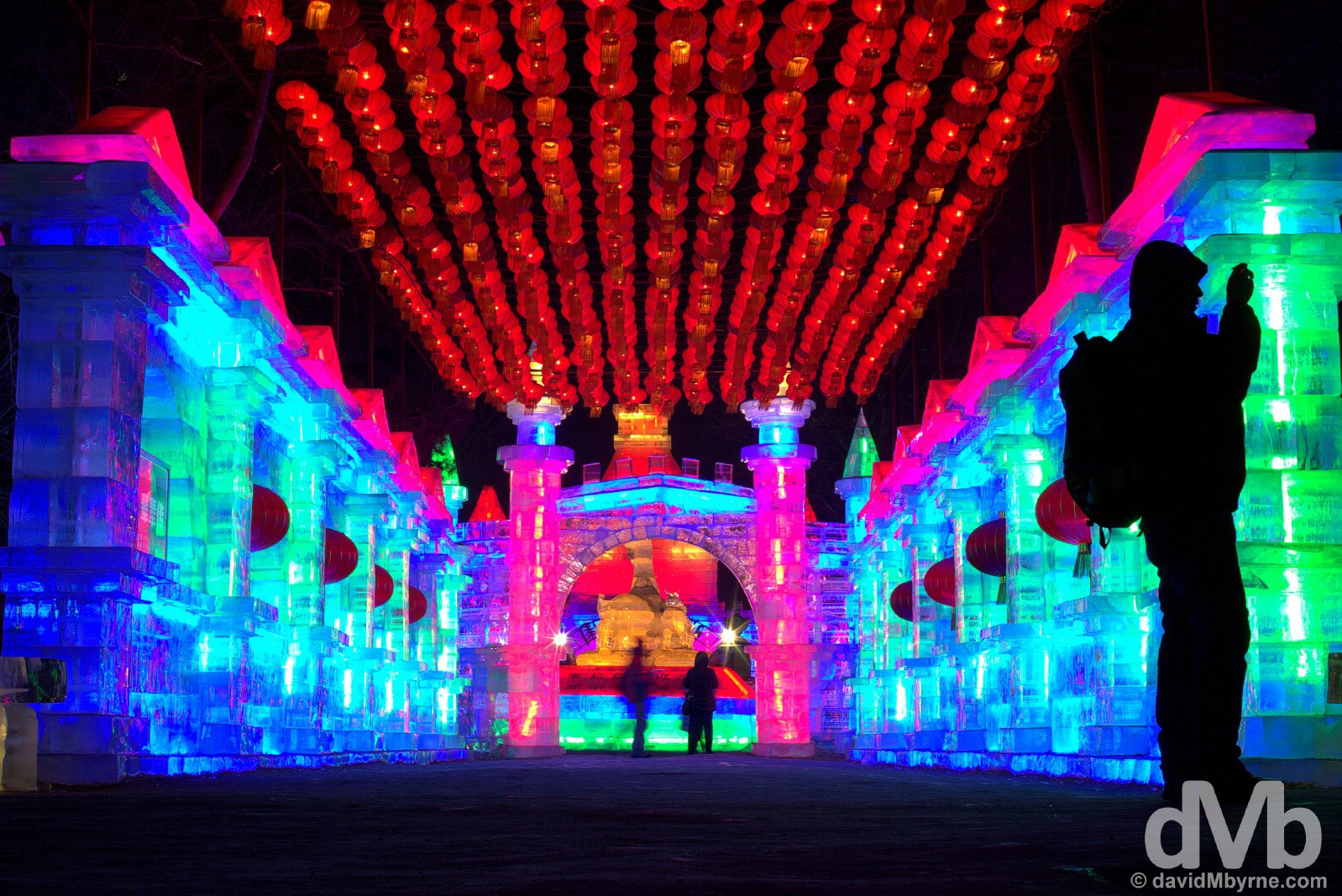

Harbin International Ice and Snow Sculpture Festival

Harbin’s main draw, and the only reason I chose to spend 19 hours on two different trains getting to & from the city from Beijing, is its annual International Ice and Snow Festival.

An ice structure in Zhaolin Park as part of the annual International Ice and Snow Sculpture Festival in Harbin, China. February 6, 2015.

Various ice sculptures, ones you can ogle at for free, line Zhongyang Dajie, but the city’s Zhaolin Park, a leafy expanse in the center of the city, is transformed for the festival to house various, more ambitious ice sculptures & structures – stairways, arches & even entire building, albeit small ones. The icy works of art are carved with picks & chainsaws and are illuminated internally to heighten the psychedelic effect. It was all, & if you’ll the pardon the oh-so obvious pun, very cool but it was also a bit of a letdown, a tad underwhelming, especially give the CNY150 (€21) entrance fee. Seemingly the mega ice structures I had expected to see are – whoops – elsewhere in the city, part of the so-called Harbin Ice And Snow World. Where that is I’ve no idea (even my hostel wasn’t too sure) and with no more Harbin time at my disposal I’ll have to revert to doing what I did prior to arrival in the city earlier today – look at the pictures online and tell myself that one day I’ll visit. Except I probably won’t.

Little & not so little feet on the ice piano in Zhaolin Park as part of the annual International Ice and Snow Sculpture Festival in Harbin, China. February 6, 2015.

Date || February 7, 2015

Location || En route from Harbin to Beijing ( )

)

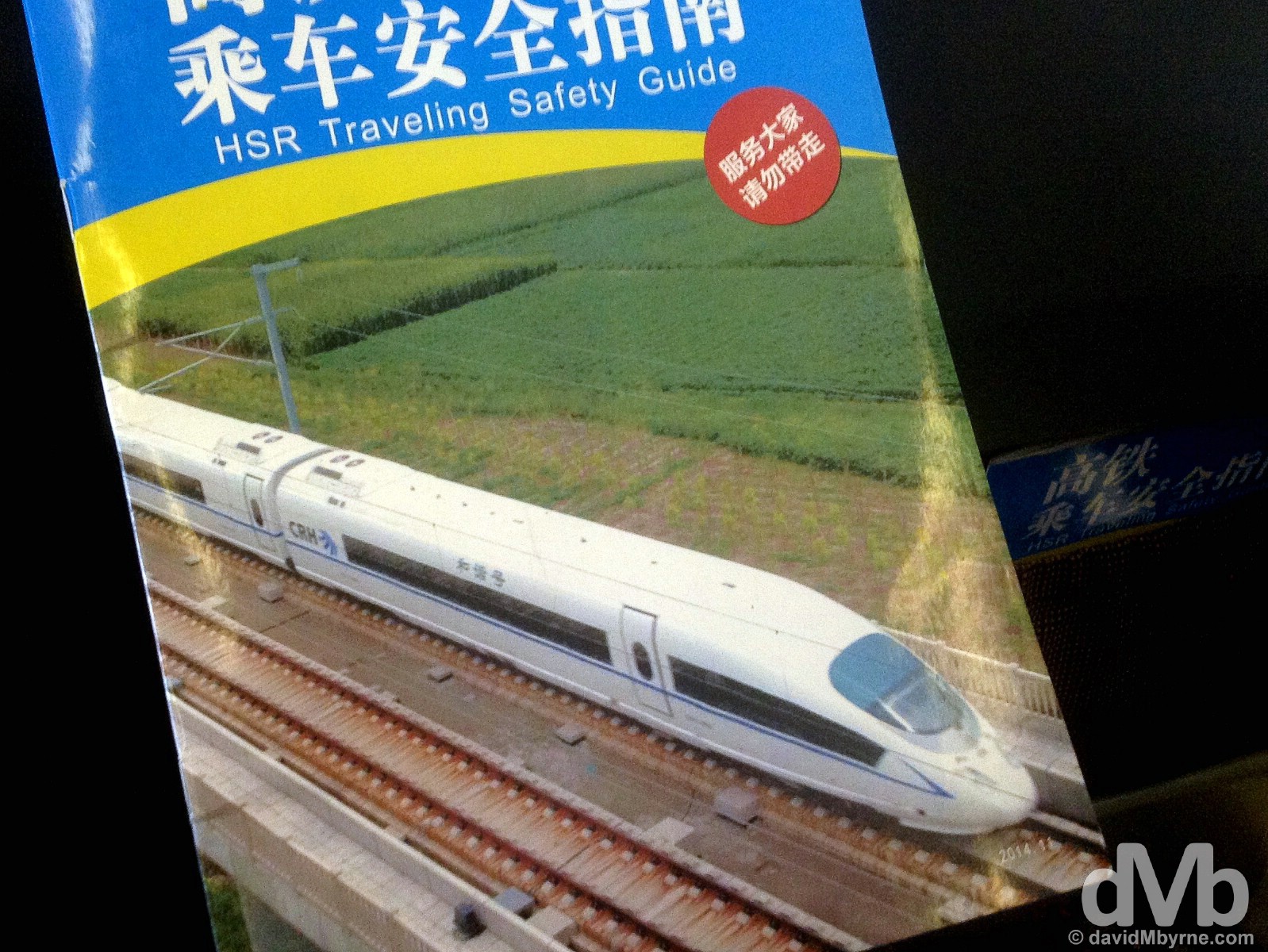

It’s 09:29 on February 7th and I’m on the high-speed train back to Beijing having spent the previous day, & night, in Harbin in northwest China. I’m sandwiched between two elderly Chinese in seat 7B. There’s an armrest either side of me that both my elbows are presently monopolising, but it may as well not be there as all three of us are nice & snug, shoulder to shoulder. This is one of those ‘new China’ trains; fast and futuristic looking. I was one one before, back in October 2012 when I took a similar train from Shanghai to Beijing, so doubtless this Chinese riding the rails experience will throw up many, if any, surprises. There’s no doubting the Chinese will to improve, and the capital outlay for investment in such projects as these high-speed rail lines must be monumentally large. But that said, corners were still obviously being cut – while this carriage has a digital readout informing those aboard of the current date, time, internal/external carriage temperatures (25/-14 Degrees Celsius right now), & train speed (191 km/h as I type), it doesn’t have comfy seats, much room, or power sockets/outlets. Oh, & the toilets still smell like all other Chinese toilets. It feels like the future on the cheap, the future ‘Made in China’. This carriage, carriage 4, does, however, come complete with a carnival atmosphere; the Chinese in here can’t seem to sit still and all 89 of them – there’s room in here for 90, me, the lone foreigner, included – seem to either know each other or want to get to know each other. It’s like they are all off on holidays, and for all I know maybe they are.

Carriage 4 of the high-speed D26 train en route from Harbin to Beijing in China. My assigned seat, 7B, is down there somewhere (to the right) but I’m choosing to spend the majority of the 8 hour trip to Beijing up and about taking pictures and smiling at the cute girls manning the dining/snack carriage. February 7, 2015.

The train is not long in motion – it left bang on scheduled time exactly 37 minutes ago, meaning I’ve another 7 hours & 30 minutes, give or take, of inquisitive stares from the locals to look forward to as we cover the 1,241 kilometres of track that separate Harbin and the Chinese capital. And with the clock ticking on the battery charge of my laptop, one of my only sources of entertainment between now and Beijing is on borrowed time. God damn you China Railways. Couldn’t the budget stretch to power sockets?

Oh I see. The provided HSR (High-Speed Railway maybe?) Traveling Safety Guide tells me I needed to have spent CNY420 (€59), CNY114 more than the CNY306 (€43) I did spend, for a business class seat in order to get a power socket. And no doubt with that would come more space & a will to actually sit down. On the D26 train from Harbin to Beijing, China. February 7, 2015.

Date || February 10, 2015

Location || Urumqi, western China ( )

)

I’m somewhat pleasantly surprised that the 39 hours I have just spent in a Chinese hard sleeper carriage (it’s not as bad/uncomfortable as it sounds) getting here to Urumqi in northwestern China passed as quickly as they did. I had positively nothing to keep me occupied – no book (except for my Central Asia guidebook that I’ve already read inside-out), no laptop (once the power died that was – lack of outlets again), no travel companion to shoot the breeze with. Nada. Of course, I had my iPod but even music & Podcasts get tiring after a while. I spent most of the journey’s daylight hours staring out the carriage window at the bleak, uninviting landscape we passed through, pitying anyone living in the numerous towns, villages and track side settlements I saw. Needless to say I took a few pictures, but not too many.

Hard Sleeper is the middle class of travel among the 5 classes of travel available on Chinese trains, offering a good balance between economy (my berth in carriage 8 for the 39-hour trip cost me CNY550, about €77) & comfort – for overnight trips in China I travel this class whenever possible. There are numerous open compartments the whole length of the carriage, each with 6 sleeping berths – 2 lower, 2 middle and 2 upper. Hard sleeper carriage 8 on the daily T177 Beijing to Urumqi train in China. February 9, 2015.

The dining car of the train. I paid a visit to photograph it. Only to photograph it. When I did, it wasn’t breakfast, lunch or dinner time so I caused quite a kerfuffle by just being here. The ladies manning the dining car tried to tell me food wasn’t available. I understood them but they didn’t understand me when I said I wasn’t looking for food. It was a hopeless situation, one only solved by me leaving & retreating back to my carriage. On the daily T177 Beijing to Urumqi train in China. February 9, 2015.

On the way back through the train I fired up the Instagram Hyperlapse app on my iPod. This is the result.

.

On long trips I like to stay awake during the day even if I have nothing to keep me occupied. Sleep during the day and you run the risk of not sleeping at night when the carriage lights are off & the carriage attendant death stares you down for NOT being in bed, both bleak predicaments. I did retreat to my upper berth a few times, although not to sleep, from where I had a good vantage point from which to view scene below me, reminding me of ‘that’ train ride in India some years ago now when I captured one of my very favourite travel memories. On the daily T177 Beijing to Urumqi train in China. February 9, 2015.

Date || February 11, 2015

Location || Urumqi, western China ( )

)

For the longest time, China has for me been nothing more than a stepping stone to somewhere else. Aside from my very first visit back in late 2004, when I spent 6 weeks touring the country in a clockwise loop from Beijing, China has only ever been in the way, somewhere I’ve used, & traversed, to get someplace else – Vietnam in 2005, Mongolia & Russia in 2006 & 2012, Tibet & the Indian Subcontinent in 2008, & now Kazakhstan & Central Asia in 2015. But I’m not quite there – Central Asia – just yet. Almost, but not quite. I’ve just one more Chinese city to deal with.

Overlooking skaters in Hongshan (Red Hill) Park, Urumqi, northwestern China. February 11, 2015.

Urumqi

Today is my 9th & last day on this my 6th visit to China. I’m spending it in Urumqi, a city on the northwest of the country. Again, it’s a big place, the political, industrial & economic capital of Xinjiang, China’s largest province and the homeland of the Uighur people. Rough Guides claims it – the city – to be ‘a drab & functional place’, a rather concise description I’d have to concur with. I arrived off the train from Beijing at 7 a.m. yesterday morning, a whole 12 hours before the departure of the next 24-hour overnight bus to Almaty in Kazakhstan, my next port of call as I head west. There’s obviously not a lot going on here in Urumqi & so, & when purchasing a bus ticket shortly after arrival in the city yesterday, I debated hard whether or not to leave at the earliest opportunity or give the city the bare minimum of 1 night. I eventually decided to stick to the original plan and stay the night – aside from anything else, I’ve been moving a lot of late (only 3 days ago I was in the largest city in the extreme northeast of the country & now I find myself in the equivalent city in the northwest) and thought I could do with staying put, even in a place as ho hum as Urumqi. All that said, Urumqi can be pretty. It’s just not that pretty for very long.

Wintry scenes in Urumqi’s Renmin/People’s Park, a park that runs right through the geographical centre of the city. Built in 1884 and renamed People’s Park in 1950 after the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, it’s full of pavilions, cottages, lakes, bridges, & monuments (and snow & ice this time of year). According to the sign fronting the park, it provides ‘a centre of relaxation, culture and entertainment’ while playing an ‘active role in enriching citizen’s life and promoting the construction of material and spiritual civilization.’ So there. Urumqi, northwest China. February 10, 2015.

Not surprisingly given its remoteness, Urumqi used to a bit of a backwater prior to the railway reaching here in the early 1960s. Now it’s just another big (population over 3 million), booming Chinese city, one with a slightly different look & feel – signs are written in Chinese & Arabic. Being China’s most westerly industrial outpost makes it an important city, so important in fact that in 1992 a bizarre decision was made to officially decree the city as a port, the idea being to attract investment through lower tax rates. As a result, it’s safe to say that the city is probably the only, ahem, port that is situated so far from the sea or ocean – 2000 kilometres, or there abouts. Indeed, the city claims to be the largest city in the world furthest from any the sea or ocean. This is a picture of Urumqi, the skyscrapers that have sprung from the plains, the haze that hangs over the city (even on a nice, sunny day like today), & of course the ever-present traffic that you find clogging the roads in any large Chinese city. It was captured earlier today from Hongshan, or Red Hill Park, a hilly & attractive park (a sign at the entrance to the park claims it to be not just a park but a ‘famous tourist resort’) not too far from People’s Park and one that offers great views of the sprawling city and the far-off snowy peaks of the Tian Shan mountains. Urumqi, northwest China. February 10, 2015. Urumqi as seen from the highest point in the city’s Hongshan (Red Hill) Park. Urumqi, northwestern China. February 11, 2015.

Central Asia Bound

The 24-hour overnight bus to Almaty in Kazakhstan leaves Urumqi in 3 hours. One of the CHY440 (€60) berths on board the bus is mine. Google maps tells me it’s a 1 hour 30 minute flight from Urumqi to Almaty but offers up an apology for not knowing the land distance. Tut tut. All I know is it’s a long way & that sometime tomorrow I’ll cross over into Kazakhstan & Central Asia proper. Given the cancellation of my North Korea tour, which was supposed to start from Beijing in two days’ time, on the 13th, I’ll be entering the region earlier than initially planned. More time I guess for pastures new.