Maracaibo, Venezuela

Money Problems In Venezuela's Colourful & Rough-Around-The-Edges Second City. A Hungry Introduction To South AmericaCalle Carabobo, Maracaibo, Venezuela. June 22, 2015.

“A lot about Venezuela seems questionable, the exchange rate of the struggling currency, the bolivar, being the obvious example. Investigating it online before arrival raised more questions than it answered. I really had no idea what to expect when I landed, a financial flummox the likes of which I’ve never before had to deal with on all of my travels. Suffice it to say, this was the first topic I broached with Nixon, my new Venezuelan bestie & chauffeur cum financial advisor.”

Venezuela

I won’t be forgetting my introduction to South America in a hurry, if at all. I never had a challenge like I had here yesterday on my first day in Venezuela, the first day of my first trip to South America, my penultimate continent (only Antarctica left). It’s 4 p.m. on Monday. I arrived last night off the plane from colourful Dutch-flavoured Curacao of the Caribbean Lesser Antilles off the north Venezuelan coast. It was late. Not too late but it was dark and when it’s dark in a strange land it’s late enough. I had it at 8 p.m. but, being Venezuela, with its own unique time zone, it was actually 7:30 p.m. Great, I gained 30 minutes. I needed every one. (UPDATE: Adopting its own timezone of UTC-04:30 between 1912 & 1965 and again between 2007 & 2016, Venezuela has since reverted back to UTC-04:00 citing a need to reduce the consumption of power that the unique timezone had demanded of the economically struggling country.) There was no semblance of order, no one in officialdom & no obvious way to get away from La Chinita International Airport into downtown Maracaibo (![]() ), some 20 kilometres away. Then Nixon appeared. My needs-to-improve-in-a-hurry Spanish told him where I wanted to go and his Spanish told me how much it would cost. Deal.

), some 20 kilometres away. Then Nixon appeared. My needs-to-improve-in-a-hurry Spanish told him where I wanted to go and his Spanish told me how much it would cost. Deal.

“Muchas gracias, amigo. Vamos!”

VW Beetle. Calle Carabobo, Maracaibo, Venezuela. June 22, 2015.

Financial Flummox

I’m not sure if Nixon was a bona fide taxi driver or not but he got me to the sanctuary of Maracaibo’s no-frills Caribe Hotel and that’s really all that mattered. A lot about Venezuela, and even at this early stage, seems questionable, the exchange rate of the struggling currency, the bolivar, being the obvious example (years of economic mismanagement has Venezuela, a country with the largest proven oil reserves in the world & one that was once so rich that Concorde used to fly from Caracas to Paris, on its knees in the midst of a deep, and getting deeper, recession). Investigating the bolivar online prior to arrival raised more questions than it answered. I really had no idea what to expect when I landed, a financial flummox the likes of which I’ve never before had to deal with on all of my travels. Suffice it to say, this was the first topic I broached with Nixon, my new Venezuelan bestie & chauffeur cum financial advisor. According to Nixon 12 bolivars (Bs.) to the US$ is the current official rate (from banks, ATMs etc.) whilst anywhere from 300-400 bolivars to the dollar the unofficial illegal but thriving black market rate. Umm. Quite the difference meaning my Bs. 1,000 hotel room can cost anywhere between $2.50 at the black market rate to $83 at the official rate. Nixon wanted to change money for me there & then in the taxi – Bs. 350 to the dollar was his offering – but for some reason I said no. That, and as it turned out, was a big rookie-in-Venezuela mistake: it meant I had to check in to the hotel last night on the back of a promise that I’d get money changed today and settle up ASAP; it meant I had no money for breakfast this morning – establishments, unlike Nixon, don’t take US dollars; and it meant I spent this morning walking around the alien & sweltering hot city looking for somewhere or someone to change money. Nothing. Nowhere & no one. All I got was hungrier, stares from some curious locals & to covet a look at a lot of decrepit, colourful, graffiti-ridden buildings. Crucially, nothing I could eat or use to settle my debt.

The colour of the Caribbean seems to have followed me here to Venezuela. On the streets of Santa Lucía, Maracaibo, Venezuela. June 22, 2015.

Still no money by lunch time. I was rather hungry at this stage. I went back to the hotel and asked the lady manning the desk where I could change money. She wasn’t helpful, wasn’t very helpful at all. It was a forlorn cause, or so I thought. Just then Ralph seemed to appear out of nowhere, à la Nixon of last night. Ralph introduced himself to me as a hotel supervisor of sorts. He was affable and seemed to genuinely care, warning me not to leave my room door open while demonstrating an impressive grasp of English in the process. Seizing the opportunity, I informed Ralph that I wanted to change money (I didn’t feel the need to explain my crusade thus far or divulge the fact that I was probably losing weight to the cause).

“Ralph, buddy. I need to change money. I’ve no money. No dinero. No bolivars. Only dollars.”

“Oh,” he said before asking me how much. I said US$60 to which he said he’d be back in 5 minutes before disappearing whence he came. An hour later he reappeared to tell me he could get a rate of 325 bolivars to the dollar.

“Grand. When?” I asked with a reserved sense of urgency. I was very hungry at this stage.

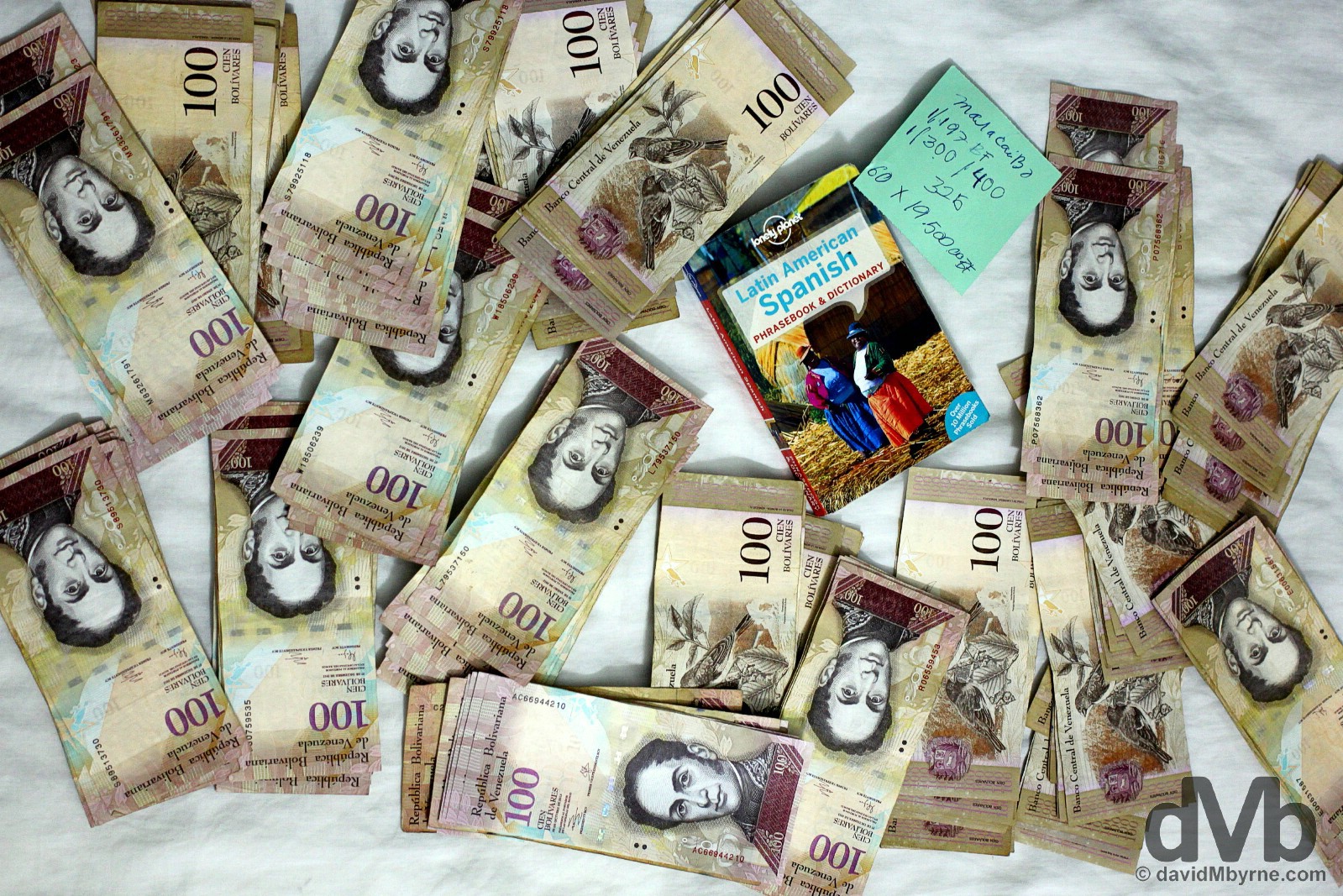

He came back 30 minutes later with a wad of notes, 195 of them to be precise (I counted, after he’d gone so as not to offend), totalling Bs. 19,500. I thanked him, profusely so while silently hoping he himself got a good deal (I’ve no doubt he did). I photographed the stash and went down stairs to part with Bs. 2,000 for 2 nights’ accommodation (that’s about $6.15, or a little over $3 a night which, incidentally, is the cheapest I’ve ever paid for accommodation anywhere) before dashing across the road to McDonald’s for a Bs. 500 ($1.53) Big Mac Meal (medium, with Sprite) that doubled as a late lunch & very late breakfast. Yes, my first meal in South America, my first purchase proper with local currency & almost 24 hours after arriving, was a McDonald’s. Judge all you like but it was delicious, even if they do serve their (cold & hard) fries out of small paper cups (they do).

This is what Bs. 19,500 looks like. BS is right. You’d need to part with approximately US$1,625 to get hold of these 19,500 Venezuelan bolivars from a Venezuelan bank, or the same amount of local currency will be delivered to your room for the cost of US$60 by the Bank of Ralph. At that rate a night in a hotel costs $3 and a meal in a restaurant, even those not called McDonald’s, no more than $2. All of that means that this wad of cash will go a long way in mid-2015 recession-hit Venezuela (the country has officially been in recession since last year). Caribe Hotel, Maracaibo, Venezuela. June 22, 2015.

It has been a bizarre first day in Venezuela. Just bizarre. And now that I’m toying with the idea of leaving tomorrow for Colombia I realise I’ve way too much money at my disposal. I mean, way too much. Ffs. From famine to feast.

DAY 3 – BORDER EXCHANGE || En route to Santa Marta, Colombia, I managed to rid myself of my excess Venezuelan bolivar, all 14,000 of them. At the Venezuela – Colombia border crossing outside the village of Guarero, northwestern Venezuela. June 23, 2015.

Maracaibo, Venezuela

Vereda del Lago by the shores of Lake Maracaibo, Maracaibo. June 22, 2015.

“…once I got my monetary woes out of the way, and once I was fed, I set about taking a proper look around the city which, and while rough round the edges in places, isn’t all that bad.”

Maracaibo, Venezuela

As a rather convenient first stop on the continent of South America when arriving from the Caribbean in the north, I was planning to pass through Maracaibo en route to elsewhere in Venezuela. As it turns out I passed through en route to Colombia. Santa Marta, northern Colombia to be precise, my present location some 380 kilometres west of Maracaibo. The northern border crossing between the two countries is only 115 kilometres, or 3 hours, to the northwest of Maracaibo, the southern crossing much further away – these South American countries are big & although it has only been a few days I already feel long since removed from the intimacy of the Caribbean islands. But that’s just a meaningless geographical observation. The real reason for heading northwest is to visit Cartagena, Colombia, billed as one of the best colonial towns on the whole South American continent. And that’s reason enough for me to limit my time in Venezuela, which admittedly was always going to be brief, to two nights, both spent in Maracaibo. And once I got my monetary woes out of the way, and once I was fed, I set about taking a proper look around the city which, and while decidedly rough round the edges in places, isn’t all that bad. It’s certainly colourful.

Blue skies, blue buildings and the blue neo-Gothic Iglesia de Santa Lucía (Santa Lucía church) in the cultural Santa Lucía neighbourhood of Maracaibo, Venezuela. June 22, 2015.

Maracaibo

Maracaibo is the capital of Venezuela’s Zuila state. It’s the country’s second city, after the capital Caracas, & the nerve centre of the Venezuela’s oil industry; Venezuela’s proven oil reserves are recognized as the largest in the world, totaling some 300 billion barrels as of mid-2015. It’s a big place, home to over 2 million. It doesn’t see too many tourists and those who do venture here stand out. Really stand out. Maracaibo feels lawless and is visually unkempt. Just worn-out looking. But the city tries hard to be pretty. To be inviting. That much is evident: it has a nice leafy central plaza, Plaza Bolivar, surrounded by some nice colonial buildings; it has some lovely churches; it boasts a nice lakefront park, Vereda del Lago; & there’s colour everywhere (but unfortunately rubbish too). So all told it’s a pleasant enough city. In places. It just won’t detain you for very long, or at least it shouldn’t.

VEREDA DEL LAGO || Vereda del Lago, Maracaibo, Venezuela. June 22, 2015.

Vereda del Lago is a big park by the shores of Lake Maracaibo, the dominate geographical feature round these arts. The park, one of the calmer spots in the city, is especially popular with joggers – plenty of running tracks keep them moving while the large ‘MARACAIBO’ sign seen here, probably the city’s most popular photo op, reminds them where they are.

LAGO/LAKE MARACAIBO || Clouds over Lago (Lake) Maracaibo as seen from Vereda del Lago in Maracaibo, Venezuela. June 22, 2015.

Sunny for the most part, there were clouds aplenty on this day hanging over 13,200 km² Lago (Lake) Maracaibo which, despite its name, isn’t a lake at all – it’s a brackish tidal bay that’s connected to the Gulf of Venezuela off the north coast of the South American continent by a narrow 5.5-kilometre-wide channel. One of the most lightening prone areas in the world thanks to a Lago Maracaibo weather phenomenon known as the Catatumbo lightning (lightening originates from a mass of storm clouds at a height of more than 1 kilometre and occurs approximately 140 to 160 nights a year for some 10 hours per day and with up to 280 flashes every hour), the lake is a major shipping route and also the scene of most of Venezuela’s oil drilling – two-thirds of Venezuela’s oil output comes from beneath Lake Maracaibo (one may be forgiven for underestimating both the wealth Venezuela sits on and the level of decades-long government mismanagement that seems intent on squandering its reserves while descending the country into something of a regional economic basket case). The lake is also the location for the General Rafael Urdaneta Bridge. Completed in 1962, the 8.8-kilometre-long cable-stayed bridge spans the outlet of the lake, and even though it’s one of the world’s largest concrete bridges, it’s still barely visible from the lake shore as seen here from Vereda del Lago.

SANTA LUCIA / EL EMPEDRAO || Santa Lucia, Maracaibo, Venezuela. June 22, 2015.

While probably not the safest area to wander, especially after dark, Santa Lucía, a small & colourful residential, commercial, religious and recreational neighbourhood, is one of the more visually impressive areas of the city during daylight hours. One of the founding sectors of the city and a renowned cultural icon of the Zulia state, it is known locally as ‘El Empedrao’ (The Empedrao) and has survived to this day as one of Maracaibo’s must-see colonial holdovers, a region of majestic stone streets, European-style narrow lanes, colourful buildings, recreation areas and some awesome street art/murals. Yes of course there’s lots of rubbish (it’s everywhere), but all that colour makes Santa Lucía feel a little less decrepit then the rest of Maracaibo.

– diariolavoz.net commenting on the Santa Lucía parish of Maracaibo

PLAZA BOLIVAR & GOVERNMENT HOUSE || Plaza Bolívar, Maracaibo, Venezuela. June 22, 2015.

Colonial Maracaibo really shines here in Plaza Bolívar, a leafy plaza that acts as the functional nucleus of the antique colonial portion of central Maracaibo. Named after Venezuelan liberator extraordinaire Simón Bolívar (1783-1830), a.k.a. El Libertador for his efforts in freeing not only Venezuela from the yoke of Spanish European colonialism but also Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Panama, the square is overlooked by some impressive buildings, one of which is the Government Palace seen here. Originally known as ‘The major house’, it dates to the 18th century but its present form is the result of an 1929 reconstruction. Previously put to use as a jail, today it serves a seat of power for the regional Government.

CALLE CARABOBO || Maracaibo, Venezuela. June 22, 2015.

Also in the colonial centre of Maracaibo and just a few blocks from Plaza Bolivar is the oh-so colourful Calle Carabobo. Stretching for 7 blocks and evoking Caribbean vibes thanks to its low-rise & abundant colour, this traditional barrio (neighbourhood) of emblematic houses is probably the best collection of preserved traditional colonial style buildings left in Maracaibo. Largely commercial & recreational as opposed to the more residential Santa Lucía neighbourhood and looking like it was lifted straight out of a Roger Rabbit movie set, there wasn’t a whole lot happening when I was wondering around, but the profusion of bars, nightclubs and live music venues along here tells me this place has a habit of going off after dark and thus is probably one of the places to be in Maracaibo when the sun goes down.

Caribe Concert, offering exclusive & guarded parking and a whole lot of colourful decorative hand prints on Calle Carabobo, Maracaibo, Venezuela. June 22, 2015.

BASILICA DE NUESTRA SENORA DEL ROSARIO DE CHIQUINQUIRA || The Catholic Basílica de Nuestra Señora del Rosario de Chiquinquirá off Plaza del Rosario de Nuestra Señora de La Chiquinquirá in Maracaibo, Venezuela. June 22, 2015.

Maracaibo is awash with churches but easily the city’s most impressive house of worship is the standout Basílica de Nuestra Señora del Rosario de Chiquinquirá. Completed in the 1850s but dating to the mid-17th century, it’s a major shrine to Our Lady of the Rosary of Chiquinquirá, a Marian title of the Blessed Virgin Mary associated with a venerated image in the northern Andes region (another major shrine with a venerated image is the Basilica of Our Lady of the Rosary of Chiquinquirá in Colombia). Overlooking the central Plaza del Rosario de Nuestra Señora de La Chiquinquirá and acting as a focal point for all Catholics in not only the city of Maracaibo but also Zulia state, the lavish 3-nave, 2-tower basilica’s most prized possession is its painted image on a small preserved wooden tablet of the Virgin of Chiquinquirá, the Patroness of Zulia state and honored on November 18 each year with city-wide celebrations marking the Feast of La Chinita.

MONUMENT & SQUARE OF OUR LADY OF THE ROSARY OF CHIQUINQUIRA || Monumento a Nuestra Senora de Chiquinquirá (Monument of Our Lady of the Rosary of Chiquinquirá), Plaza del Rosario de Nuestra Senora de Chiquinquirá (Square of Our Lady of the Rosary of Chiquinquirá), Maracaibo, Venezuela. June 22, 2015.

Off-limits when I was snooping round, the Monument of Our Lady of the Rosary of Chiquinquirá sits in the centre of the Maracabio’s 30,000 m² Square of Our Lady of the Rosary of Chiquinquirá. The monument forms a semi-circular open sanctuary in the centre of which, and facing the Basílica de Nuestra Señora del Rosario de Chiquinquirá, is an unmissable 15-meter-high allegorical statue of the Virgin of Chiquinquirá depicted as on the basilica’s venerated wooden tablet, holding the baby Jesus in her left arm.

CHAVEZ || A Hugo Chavez mural and quote (translated below) to his detractors on Avenida Padilla Calle 93, Maracaibo, Venezuela. June 22, 2015.

Born in 1954 into a working-class family, Hugo Rafael Chávez Frías was a career military officer and the oft-controversial 45th President of Venezuela (in power 1999-2013). When he came to power in 1999, there was hope. He was a man who championed the poor in what has always been a deeply divided society. Vibrant and controversial in equal measure and a prominent adversary of US foreign policy as well as a vocal critic of US-supported neoliberalism and laissez-faire capitalism, he described himself as a Marxist and had a vision to lead a socialist revolution in Venezuela funded by strong commodity prices. He died of cancer in 2013 at the age of 58 with many a commentator in agreement that the squandering of resources, prolonged economic mismanagement and failure of many of the ambitious populist policies of his so-called “Chavismo” political ideology were the catalyst for the severe socio & economic crisis Venezuela finds itself in today, and all this despite its unrivaled proven oil reserves (four in every five Venezuelans live in poverty & the current president Nicolás Maduro, a Chavez disciple in power since April 2013, isn’t helping the cause, blaming “imperialists” – the likes of the US and Europe – for waging “economic war” against Venezuela and imposing sanctions on many members of his government).

– Hugo Chávez