Skopje, Macedonia

”Most of what bemused me about the city today wasn’t even here a decade ago. Millions have been spent in recent years turning the centre of the city into something of a bizarre theme park of garish architecture – some 130 structures (buildings, statues, bridges, water features, and even a triumphal arch) were erected between 2010 and 2014 as part of the Skopje 2014 project, one of Europe’s biggest urban renewal schemes centred around both banks of the city’s Vardar River.”

Image || Crossing the iconic Stone Bridge in Skopje, Macedonia. April 24, 2017.

Skopje, Macedonia

Yesterday I left Pristina, Kosovo, a Balkan capital that hasn’t a bean to rub together, to arrive in another Balkan capital – this one – that has spent many hundreds of millions of dollors turning its city centre into something of a tacky mock-up of a Las Vegas-esque mock-up, if you follow? It’s quite the sight and even after two days of exploration I still don’t know what to make of the revamped Macedonian capital of Skopje.

Selfie fronting the Fountain of The Mothers of Macedonia in central Skopje, Macedonia. April 24, 2017.

dMb Country Overview - Macedonia

Macedonia

Macedonia

Region – Southeastern Europe/The Balkans (dMb tag: The Balkans). Capital – Skopje. Population – 2 million-plus. Official Languages – Macedonian, Albanian. Currency – Macedonian Denar (MKD) GDP (nominal) per capita – US$6,140 Political System – Unitary parliamentary republic. EU Member? – No (as of April 2017). UN Member? – Yes (admitted April 1993 using the name, under the instance of neighbouring Greece, Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM)). G20 Member? – No. Size – 25,700 km² (Europe’s 14th smallest country is approximately half the size of Costa Rica and slightly larger than the US state of Vermont). Topography – Mountainous and rugged. Brief History – It’s complicated, as Balkan history tends to be. Inhabited since Neolithic times, the region was the homeland of one Alexander III of Macedon (aka Alexander the Great, born in Pella in present-day Greek region of Macedonia in 365 BC) who set forth from here to conquer the ancient world in the 4th century BC. The Romans held sway (from approx. 160BC), the Byzantines (from 395 AD), the Bulgarians, Serbia, and finally the Ottoman Turks who ruled for over half a century (from 1389 to 1912). Then came almost a century of more upheaval and Yugoslav Communist rule, before independence in 1991, something of a novelty up to that point for the long-oppressed Macedonians. Formation/Independence – 1991 following the breakup of the former Yugoslavia (and in what was the only peaceful withdrawal of the former Yugoslav army from any of its former republics). UNESCO World Heritage sites – 1. Tourism Catchphrase/Slogans – Macedonia Timeless. Famous For – Alexander the Great; Mother Theresa (born in Skopje); Lake Ohrid. Highlights – Shimmering Lake Ohrid, the jewel in Macedonia’s crown; remnants of the ancient past – Roman ruins and Byzantine-era churches; wilderness hikes; garish ‘New’ Skopje.

Name Note (2019 Update): – What’s in a name? A lot, seemingly. The naming of this little country has always been a thorny issue, one that has stoked tensions with neighbouring Greece for close on 3 decades now – Greece felt that the use of the name Macedonia following the mini-state’s independence from Yugoslavia in 1991 constituted a territorial claim on its own northern region of the same name (international recognition of Macedonia’s independence was delayed by Greece’s objection to the new state’s use of what Greece considered a “Hellenic name and symbols.” Greece finally lifted its trade blockade in 1995 and the two countries agreed to normalise relations, this despite continued disagreement over the use of “Macedonia” in the name). Since independence Macedonia was forced to call itself the rather convoluted Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM) on the international stage, a title given to it by the UN and a title the Greeks were happy to roll with, even if 132 countries had recognised it as the Republic of Macedonia, its former constitutional name. In a bid to end one of Europe’s longest-enduring diplomatic rifts, and after years of negotiations, the country agreed, in 2019, to prepend the word ‘North’ to its name to help distinguish itself from the neighbouring northern Greek region, a move the Macedonians hope will accelerate its path to eventual EU accession. On my two visits to the country (in 2007 and 2017), the country was called (the Republic of) Macedonia and is thus referenced as such throughout my postings as opposed to its new official name of (the Republic of) North Macedonia.

Souvenirs for sale in the Old Bazaar, Skopje, Macedonia. April 24, 2017.

Visits – 2 (April 2017 and September 2017). Where I went/What I saw – Ohrid (2007 & 2017); Skopje (2017).

This isn’t my first Skopje rodeo. I was first here during the summer of 2007. That was a brief sojurn and I don’t remember a whole lot about the 2007 city of Skopje, but it certainly wasn’t back then what it is now (trust me, I’d have remembered). Skopje 2014 has been and gone in the interim, and just look at what it has left in its wake.

Both errected as part of the Skopje 2014 project, the Greek Revival Museum of Archaeology and the Eye Bridge spanning the Vardar River in Skopje, Macedonia. 23 April, 2017.

White white elephants stand out. A lot of white white elephants really stand out. Most of what bemused me about the city today wasn’t even here a decade ago. Millions have been spent in recent years turning the centre of the city into something of a bizarre theme park of garish architecture – some 130 structures (buildings, statues, bridges, water features, and even a triumphal arch) were erected between 2010 and 2014 as part of the Skopje 2014 project, one of Europe’s biggest urban renewal schemes centred around both banks of the city’s Vardar River. The over-the-top building bonanza, estimated to cost a whopping US$700 million, was financed by the then Macedonian government. Its official purpose was to give the city a more aesthetically pleasing and classical appeal (and it’s wholly subjective as to whether it succeeded or not), but simultaneously it served to advance the overtly nationalist government’s so-called “antiquisation” policy: at a time when Macedonia’s identity was perceived under threat because of the long-running dispute with Greece over the use of the name Macedonia, the policy, it is believed, sought to claim ancient Macedonian figures like Alexander the Great and Philip II of Macedon as national heroes, much to the ire of the Greeks (both were born in Pella in the present-day northern Greek region of Macedonia). While some might have lauded the project’s ambition to create a showpiece Balkan capital that both boosted national pride and built a national identity (even though this is a nation that already boasted an oh-so complex and fascinating history), the project was widely derided by architects, locals (who dismissed its works as nationalistic kitsch), and subsequent governments, the latter obviously keen to redress the antagonistic overtures of the past in a bid to improve regional relations – in early 2018 some of the project’s more controversial structures were removed altogether while the remaining structures were renamed and marked with inscriptions honouring Greek-Macedonian friendship.

SKOPJE 2014 – MACEDONIA SQUARE & THE WARRIOR ON A HORSE MONUMENT || The Warrior on a Horse Monument in Macedonia Square, central Skopje, Macedonia. April 24, 2017.

The centrepiece of the Skopje 2014 project, sitting pride of place in the city’s central and expansive Macedonia Square, is the Warrior on a Horse Monument. The massive structure, erected in 2011 to commemorate 20 years Macedonia’s independence and surrounded by a fountain with 16 bronze sculptures (8 3-metre-tall soldiers and 8 2.5-metre-tall lions), stands an impressive 22 metres (72 feet) tall. Visible from afar any time of day, it also puts on an impressive water, light and sound show at night. A steal then at an estimated US$8 million. Of all the controversial structures erected as part of the Skopje 2014 project, the bronze mounted figure of this monument, cast in Florence, Italy, was, and still is, the most controversial of the lot (although it still survived the 2018 improve-relations-with-the-Greeks cull of the worst offending of Skopje 2014’s kitsch). Although widely thought to depict Alexander the Great (it bears an uncanny resemblance to the warrior king) seated upon his favourite steed, it is not officially named for him and in these times of improving neighbourly harmony no one would — shh! — ever dare suggest it does.

SKOPJE 2014 – BRIDGE OF ART || Crossing the Bridge of Art spanning the Vardar River in Skopje, Macedonia. 24 April, 2017.

Erected in 2012 and with a price tag of some US$2.7 million, the Bridge of Art is one of two new pedestrian bridges built to span the city’s Vardar River as part of the overall Skopje 2014 project. Measuring 83-metre-long (272 feet), the statue-heavy bridge features many a bronze representation of noted Macedonian cultural icons, 35 in total representing some of the most significant and distinguished educators, artists, writers, composers and actors, all of whom, so claims the bronze plaque adorning the bridge, left ‘a treasury of works and cultural wealth that form an invaluable part of the Macedonian cultural heritage’.

STONE BRIDGE/KAMEN MOST || The Stone Bridge/Kamen Most spanning the Vardar River in Skopje, Macedonia. 23 April, 2017.

I found it somewhat ironic, although not all that surprising, that my highlight of present-day facelifted Skopje is one of its oldest structures, one that sits slap bang in the middle of the city connecting one area of city kitsch to another (and trying to get a picture anywhere in the city centre region from either side of the Vardar River while avoiding some of that kitsch is a real challenge). A symbol of the city, the 13-arch, 214-metre-long (700 foot) Stone Bridge (yes, it’s built of stone blocks) was first built in the 6th century by the Byzantine emperor Justinian – the current structure was built on Roman foundations and dates to the mid-15th century. Although last renovated in the mid 1990s, it has stood the test of time rather well, ageing way better than the less-than-a-decade-old structures surrounding it. They sure don’t make cities like they used to.

By the banks of the Vardar River off Macedonia Square in central Skopje, Macedonia. April 23, 2017.

Thankfully there’s more to Skopje than city centre kitsch, and it’s a tale of two cities once you get away from the banks of the Vardar River which conveniently divides the city into distinct north and south districts: north of the river is the older part of the city where the you’ll find the cafes, kabab shops, Orthodox churches, and Ottoman-era mosques among the cobbled lanes of the Old Bazaar/Stara Carsija, not to mention the stunning views from the reconstructed walls of Skopje/Kale Fortress, the highest point and oldest structure in the city; whereas south of the river, the so-called New Centre, is home to a proliferation of classical Communist-era Eastern European concrete, most of which was hastily erected following the devastation caused by the 1963 earthquake that rocked the city, changing it forever.

SOUTH SKOPJE – NEW CENTRE – CITY MUSEUM & 1963 SKOPJE EARTHQUAKE || The façade of the City Museum in the old railway station in Skopje, Macedonia. April 23, 2017.

Classical Eastern European modernist architecture first appeared in Skopje in the early part of the 20th century and was ramped up following the establishment of the Yugoslav state in 1918. Under Yugoslav rule, the city developed rapidly up until the devastating 1963 Skopje earthquake which flattening 80% of the buildings in the city. Skopje was largely rebuilt in the years following as a proper modernist city, with large blocks of flats, austere concrete buildings, and scattered green spaces. However, earthquake damage is still visible today, notably the partly-ruined exterior of the city’s old railway station which still stands as a memorial to the disaster. Built in 1940, today the modernist eyesore houses the City Museum, Skopje’s premier memorial to a disaster that killed over 1,000 people and changed the face of the city forever; the Skopje 2014 project was a garish facelift of the plain modernist architecture erected following the earthquake which flattened most of the neoclassical buildings that had stood in the central part of the city – the epicentre of the quake was directly under the city’s central Macedonia Square.

SOUTH SKOPJE – NEW CENTRE – CITY MUSEUM & 1963 EARTHQUAKE || The stuck-in-time clock on the façade of the old railway station in Skopje, Macedonia. April 24, 2017.

Poignant. The clock on the façade of the old railway station frozen at 5:17, the time on July 26, 1963 that the earthquake struck.

SOUTH SKOPJE – NEW CENTRE – MACEDONIA STREET ||Macedonia Street, leading from the City Museum/old railway station to Macedonia Square, one of the busiest pedestrian precincts in the city. Skopje, Macedonia. April 23, 2017.

SOUTH SKOPJE – NEW CENTRE – MEMORIAL HOUSE OF MOTHER TERESA || The confused-looking Memorial House of Mother Teresa in Mother Teresa Park off Macedonia Street, Skopje, Macedonia. April 23, 2017.

I wasn’t quite sure what to make of this either. Another Skopje architectural oddity, the structure was built between 2008 and 2009 as a memorial-cum-museum to the Roman Catholic nun, missionary, humanitarian, and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Mary Teresa Bojaxhiu, a.k.a. Mother Teresa, born Agnes Gondzha Bojaxhiu here in Skopje on August 26, 1910, when the city was then part of the Ottoman Empire. Built in the small Mother Teresa Park off Macedonia Street on the very site of the former Sacred Heart of Jesus Roman Catholic Church, where Mother Teresa was baptized, the building is a curious mix of styles – according to Wikipedia, it is a ‘modern, transformed version of Mother Teresa’s birth house with a multifunctional but sacral character’.

SKOPJE 2014 – SOUTH SKOPJE – CHURCH KONSTANTIN & ELENA || The Ortodox Church Konstantin and Elena in Mother Teresa Park off Macedonia Street, Skopje, Macedonia. April 24, 2017.

Controversy here, too. Constructed as part of the Skopje 2014 project, the Orthodox church dedicated to Saints Constantine and Helena was supposed to be located just off Macedonia Square, in eyeshot of the rest of the Skopje 2014 project eyesores, but it was moved to a somewhat sheltered space in the small Mother Teresa Park off Macedonia Street as a result of civil, political and religious uproar – if the Orthodox Macedonians were going to get a brand new place of worship financed with public money and in a prime location on the city’s central square, then so were the country’s Islamic Community in the form of a new mosque. Friction between the two led to violence, the muslims didn’t get their mosque, and ultimately the church was moved to a site away from the square. At least the building’s gleaming gold and white travertine (a type of limestone) brings a little brightness to the dullness imposed on this southern portion of the capital by communist apparatchiks in the wake of the 1963 Skopje earthquake.

Playing with the fountains in Macedonia Square, central Skopje, Macedonia. April 24, 2017.

Crossing the Stone Bridge over the Vardar River and negotiating a path past the proliferation of Skopje 2014 statues brings you to the lanes of the city’s Old Bazaar/Stara Carsija, the historical core of the city. Well removed from the socialist era buildings found south of the Vardar River, there’s very little here that is dull and boxy.

NORTH SKOPJE – OLD BAZAAR/STARA CARSIJA || In the lanes of the Old Bazaar/Stara Carsija, Skopje, Macedonia. April 24, 2017.

The city’s industrious, lively and disorderly centre of commerce during the 500-year-plus Ottoman rule of the city (from the mid-14th century until 1912), the Old Bazaar/Stara Carsija is still a warren of lanes awash with jewellery stores, cafes, sheesha bars, kebab stalls, Turkish bathhouses, and mosques, some 30 in total. Razed many times over the centuries and with a checkered past, recent investment by government hopes to realise the region’s full potential as a tourist, economic and cultural hub.

NORTH SKOPJE – OLD BAZAAR/STARA CARSIJA || In the lanes of the Old Bazaar/Stara Carsija, Skopje, Macedonia. April 23, 2017.

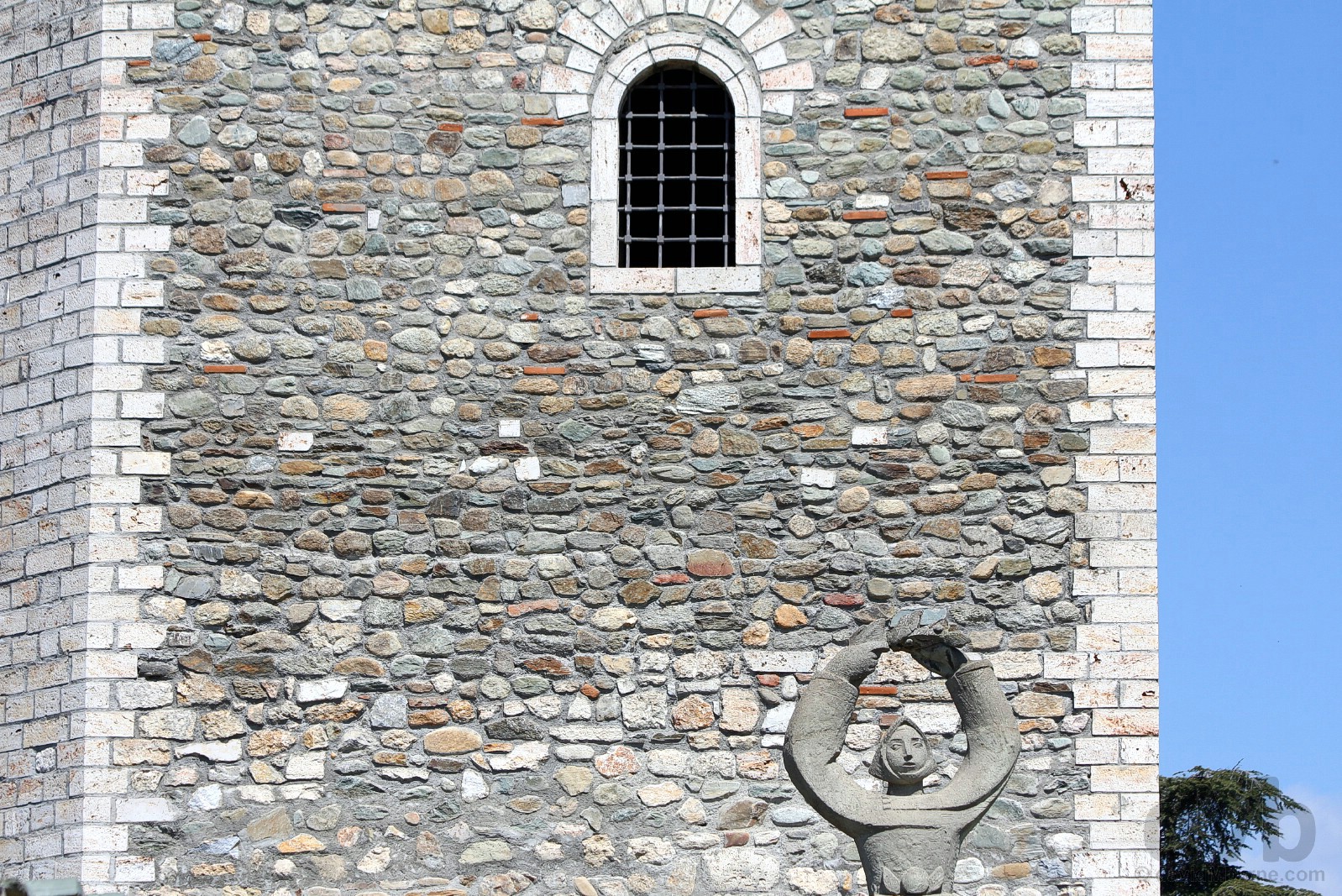

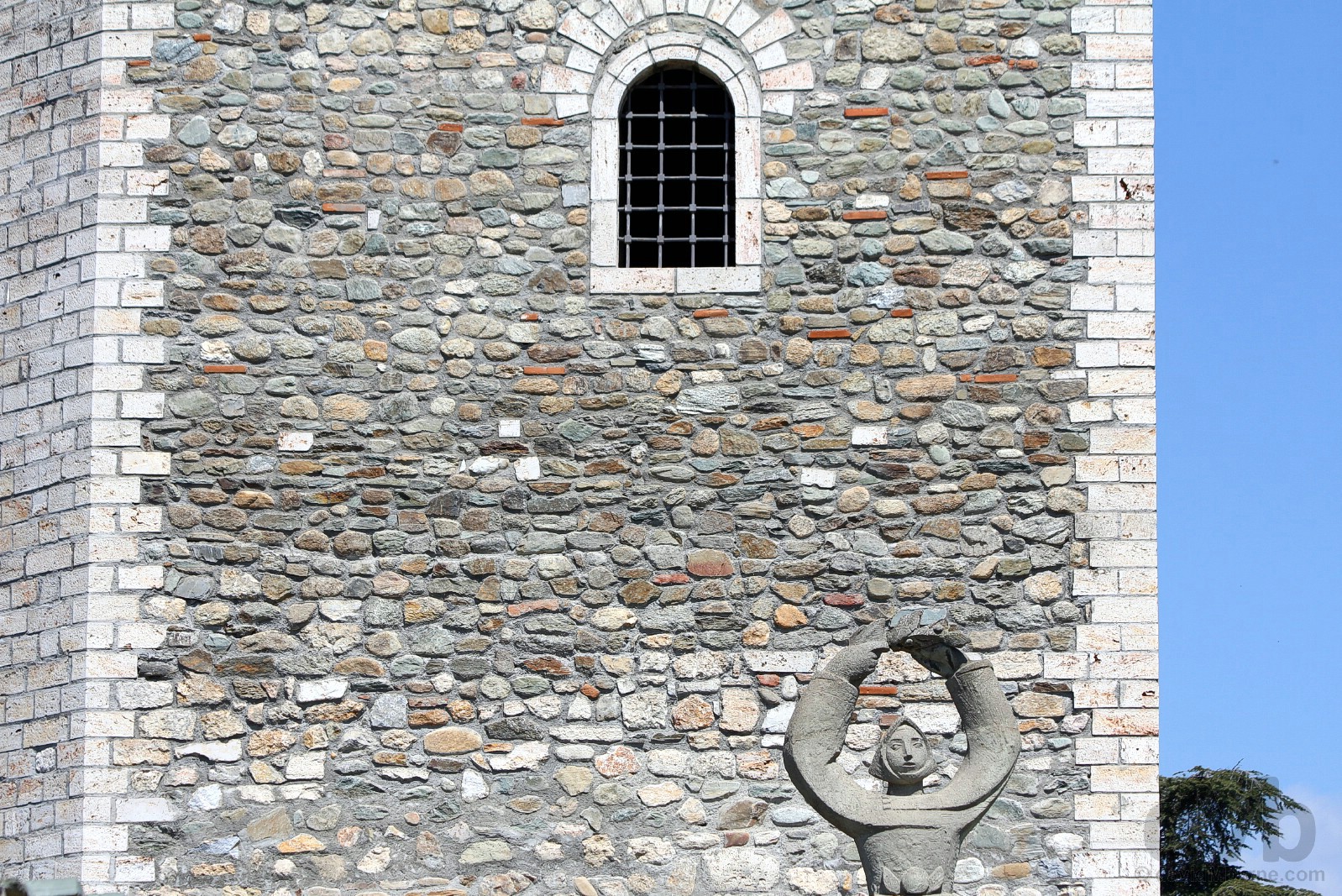

NORTH SKOPJE – SKOPJE/KALE FORTRESS || A restored tower of Skopje/Kale Fortress, Skopje, Macedonia. April 24, 2017.

Perched atop the highest hill in the valley which Skopje finds itself in, Skopje/Kale Fortress occupies the highest point in the city. A landmark depicted on the city’s flag and coat of arms (along with the Stone Bridge), there has been a fortress here since Byzantine rule of the 6th century, but it has been rebuilt many times and nothing of the 6th century structure survives to this day. Parts of the present walls date to the 11th century, although reconstruction in recent years, especially of the battlements and towers destroyed in the 1963 earthquake, means portions of the fortress appear so new so as to belie its status as the oldest structure in the city.

NORTH SKOPJE – SKOPJE/KALE FORTRESS || Northern Skopje as seen from the walls of Skopje/Kale Fortress, Skopje, Macedonia. April 24, 2017.

Occupying the highest point in the city means the views from the walls of Skopje/Kale Fortress are impressive, including the view seen here looking towards the mountain range that acts as the border with neighbouring Kosovo to the Northeast.

NORTH SKOPJE – MUSTAFA PASHA MOSQUE || The 42-metre-high (140 feet) limestone minaret and 16-metre-wide (52 feet) dome of the Mustafa Pasha Mosque as seen from the walls of Skopje/Kale Fortress, Skopje, Macedonia. April 24, 2017.

The Ottoman-era Mustafa Pasha Mosque in Skopje’s Old Bazaar is probably the city’s most recognisable mosque, not to mention one of the most elegant Islamic buildings in Macedonia. Built in 1492 by Mustafa Pasha on an older Christian site, the mosque has changed much down through the years – it has received little structural change since its construction and underwent a five-year renovation between 2006 and 2011 that was funded by the Turkish government.

Signing Off | The Complete Skopje Gallery